Understanding the auction consignment process

In the latest Behind the Gavel column, Wayne Jordan discusses consigning items at auction, and the importance and impact of understanding the ins and outs of the process.

Arguments rage as to whether it’s better to consign collectibles for resale via auction or to sell them oneself via private treaty. Detractors of the auction method say that auction house fees are too high: up to 50 percent of an item’s final price. Auction enthusiasts say that the auction method of selling is inherently better and ultimately brings higher prices regardless of the fees. Which point of view is right, and what difference does it make?

Depending on what you’re selling, either point of view can be right, and knowing which point of view is best for your circumstances can mean more — or fewer — dollars in your pocket. If you’re considering consigning your collections for resale, here are some points you may wish to consider before consigning to an auction house.

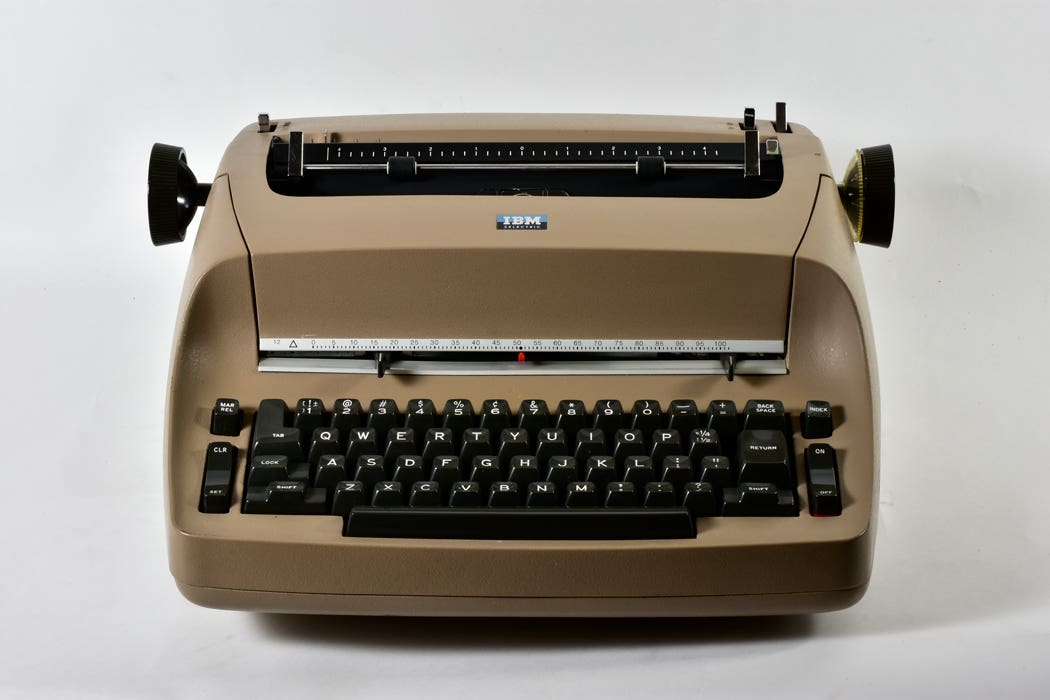

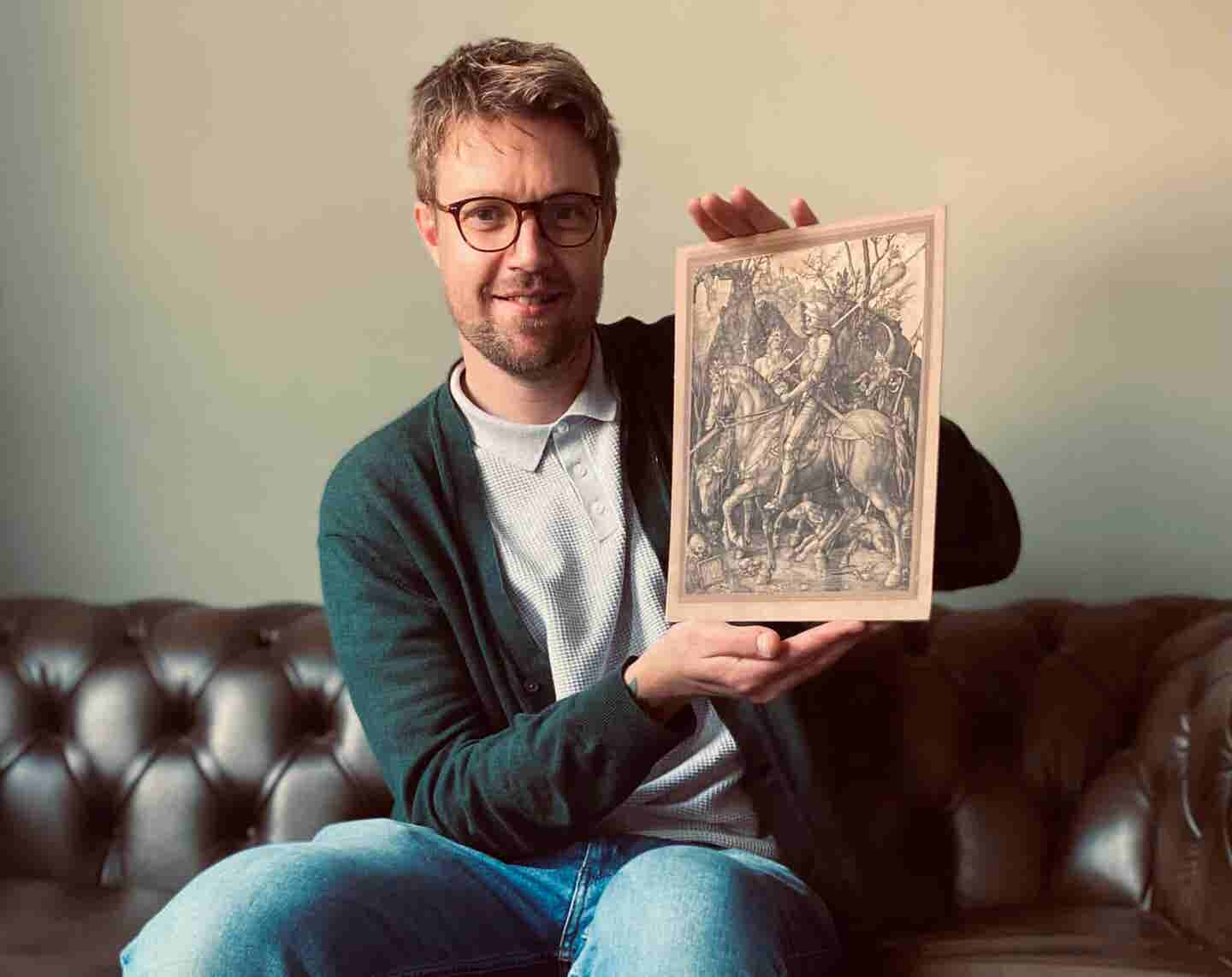

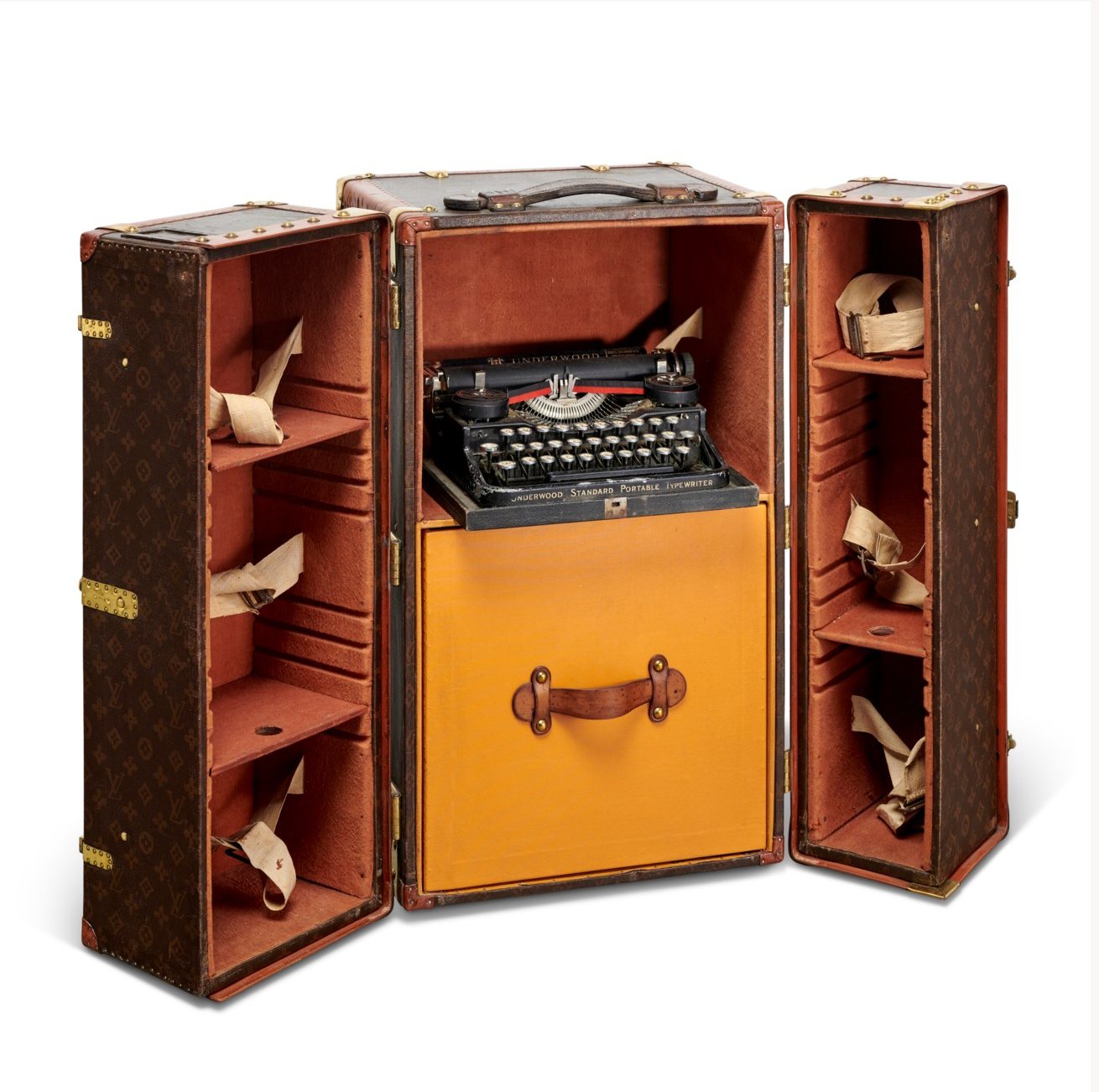

1. Make sure your items are genuine. Generally, serious collectors know that their items are the “real deal.” But when collectibles are inherited or sold through an estate executor, a collection’s provenance may come down to family hearsay. This is where the advice of a reputable auction house or appraiser can be invaluable. Auction houses that specialize in the types of items you wish to sell will be able to tell you if your items are genuine or not.

2. Make sure you have clear ownership of all the items in the collection, and that you have the authority to sell them. Of course, if the collection is yours, you’re sure to know where everything came from. But in estate situations, one can never be entirely sure unless there’s a paper trail (and maybe not even then). Collectibles are sometimes stolen or borrowed, and thieves may re-sell stolen items to unsuspecting collectors. One cannot acquire good title from a thief. If you’re not sure of an item’s origin, be sure to tell the auctioneer.

3. Find an appropriate auction house. The easiest and best way to do this is to peruse Antique Trader and other antiques trade ads, looking for a company that specializes in the type of item you wish to sell. Any company that regularly invests in print advertising is a company that has their consignor’s best interests in mind. Speak with several auctioneers about your items, and give them as many details as you are able. Most will tell you how to proceed if they are interested, or will give you a referral if they’re not.

Auctioneers will want to inspect your collection before accepting it on consignment. Generally, they will start by having you send them photographs of the items in your collection. Digital photos are best, because they can be enlarged and manipulated. Using adequate resolution (ask the auctioneer what she requires), take photos of each object in the collection in well lit areas and in focus. Be sure to photograph identifying marks and/or damaged areas. Also, provide any provenance that you might have: bills of sale, documentation or old appraisals.

Based on your photos, if an auctioneer is interested in your consignment, he will want to see and handle the item(s). If the auctioneer is close, you can set an appointment for him to come to your house for an inspection, or go to his gallery. If the auction house is at some distance, you may arrange for the item to be shipped. If you ship, be sure the items are well insured. Also, make sure that the insurance will cover items that are “PBO” or packed-by-owner.

4. Receive auction estimates. It’s unlikely that an auctioneer will give you an actual appraisal for your items. Instead, she will give you an “auction estimate” or a price range for which your items might sell at auction. Such an estimate is not a guarantee, however; it is a guesstimate based on what similar items have sold for. Your items may sell for more, or perhaps a lot less. If you are unwilling to accept any amount below a certain price for your collection, then tell the auctioneer that you want to place a reserve (a price below which the items won’t be sold). Auctioneers don’t generally like reserves, and neither do bidders. Too many items with reserves inhibit bidding.

5. Discuss the fees. These days most companies will charge fees and commissions to both the seller and the buyer. Fees that a seller may incur are: a percentage of the “hammer price” (final bid), a flat fee for non-selling items that have a reserve, photography, online listing, inclusion in a printed catalog, insurance, transportation and cleaning or restoration. Be sure to review the auctioneer’s fees and understand how they will apply to you.

Buyers are charged a “buyer’s premium,” or a percentage of the hammer price. A buyer’s final price consists of the hammer price + buyer’s premium + taxes + packing and shipping charges (if any). Buyer’s premiums are charged so that auctioneers can reduce commissions for sellers. Auction houses “live or die” by the quantity and quality of the consignments they receive. So, they frequently cut seller commissions to get quality consignments and make up the difference by charging the buyers a premium.

Savvy buyers consider their total costs when bidding on items, and bid less when buyer’s premiums are in play. Do buyer’s premiums reduce seller’s net proceeds from a sale? It depends on the auction. Auction prices are driven by competitive bidding, so more bidders equals higher prices. Auctions that offer a good selection of quality items will attract a lot of bidders and drive prices up. Ultimately, a well-attended auction will result in a higher net for sellers despite a buyer’s premium.

6. Discuss the scheduling. Themed auctions attract more bidders, so an auctioneer may want to delay selling your collection if it fits with a particular theme. If you have items that fit with several themes, it could take months to get all of your items sold. If you’re not in a hurry, this tactic will put more money in your pocket.

7. Review the contract. Auction houses are governed by the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) and

UCC will rule whether your auction agreement is in writing or not. But it’s always best to have a written agreement, and most auction houses will insist on one. Simple, one-page contracts may be sufficient for household goods, but your valuable collection deserves better protection. For example, standard auction house contracts usually include “rescission” clauses that allow auction houses to reverse a sale, refund the purchase price to the buyer and demand a refund from the consignor if authenticity issues arise even years after the auction. Also, title to your item transfers when the item is delivered to the buyer whether it’s paid for or not; if the buyer doesn’t pay, you can’t get your item back. Of course, reputable auction houses will (usually) pay you even if the buyer doesn’t pay. My point is that auction contracts can be complicated and are written to protect auction houses, not sellers. Make sure you understand the implications of everything in the contract before you sign it. If you’re not sure, consult an attorney. Don’t be your own lawyer. The greater the value of your collection, the more important this is.

Consigning your collection to auction is the best way to sell it: You will almost always net more money than you would selling another way. In most states auctioneers are licensed fiduciary agents who must adhere to the law regarding your consignments. Even in non-license states, a good auction house will want to keep their reputation unblemished and will treat you fairly. Before you sign the consignment contract on the dotted line, make sure you have a thorough understanding of the auction process.

Longtime columnist, writer, and author, Wayne Jordan is an antiques and collectibles expert, retired antique furniture and piano restorer, musician, shop owner, auctioneer, and appraiser. His passions are traveling and storytelling. He blogs at antiquestourism.com and brandbackstory.com.