Understanding, navigating ‘added fees’ circuit

In this Behind the Gavel column, Wayne Jordan examines the increase of ‘added fees’ becoming part of some business operations.

Buyer’s fees are much like kudzu: They are invasive, spread rapidly, and choke the life out of everything they touch.

Likening Fees to Kudzu Plants

For those unfamiliar with the plant, kudzu was introduced into the United States at the 1876 U.S. Centennial Celebration by the Japanese contingent. It was immediately adopted in the Southern U.S. as cheap animal fodder and to control soil erosion. In the 141 years since kudzu’s introduction, it has become known as “the plant that ate the South.” The vine grows about a foot a day and is nearly impossible to kill. Left unchecked, it will completely cover mountains, houses, barns, and trees. Power companies spend over $1.5 million per annum repairing kudzu damage to power lines; landowners spend nearly $2,000 annually per acre to control the weed, and it’s estimated that (nationally) between $100 to $500 million in forest productivity is lost each year.

Once it gets a foothold, it’s nearly impossible to stop; much like auction buyer’s premiums, which suck the life out of auctions, obscure the true value of items and diminish auction crowds [http://bit.ly/2q2nWp3].

Here's an illustration....

Examining the Trend of Passing on Costs

I’m sorry to say that the “pass the selling costs to the buyer” trend is spreading. Recent battlegrounds for squeezing extra dollars from buyers are consignment shops and estate tag sales. A couple of months ago I read a blog post by Deb McGonagle at Traxia titled “Five Consignment Fees to Boost Your Bottom Line” [http ://bit.ly/2qn3eDx]. Let me say out-of-the-gate that I’m a Deb McGonagle fan; she thinks and writes clearly. Her discussion of consignment fees is simply reporting; she doesn’t express an opinion. I’m more generous with my opinions (as regular readers are aware). The fees discussed are:

Buyer’s fee

Tacked onto an item’s sticker price, it is paid by the buyer and deducted from the selling price before settling with the consignor. The shop keeps the fee.

Item fee

Consignors pay for the privilege of taking up your shop space, the fee is deducted from settlement proceeds.

Credit card processing fee

Paid by the consignor and deducted from settlement proceeds.

Check fee: Not a fee charged to customers who want to write a check; it’s charged to consignors to cover the cost of printing and mailing them a settlement check.

Consignor access fee

Charged monthly to all consignors for the privilege of viewing their account online, whether or not they actually view their account online.

Who Bears the Burden of Fees?

I don’t begrudge any owner a healthy profit. Selling on consignment at a fixed commission is particularly tough, because the only way to boost margins as expenses rise is to boost commissions – or keep commissions flat and pass some costs on to buyers. But let me be clear: All of these fees (just like buyer’s premiums and associated auction fees) are smoke and mirrors meant to deceive sellers into thinking that they are paying less to get their goods sold.

Who bears the burden of the added fees? The buyer? No; consignment and estate buyers have time to research prices and make informed decisions. Unlike auction buyers, there is no competitive bidding pressure to quickly drive up a price; the price on the sticker is the selling price. The price may go down, but not up.

Is the “added fees” burden assumed by the dealer? Hardly; fees go right into their bank account to pay expenses.

Doing the Math

Decidedly, the burden of added fees falls upon sellers (consignors). Why are sellers willing to pay commission-plus-fees when they may be better off with a (higher) commission-only contract? For starters, it’s hard to know in advance what an item will ultimately sell for or how long it will take to sell it. Also, one never knows whether a buyer will use a credit card or not. When uncertainty surrounds the fees, most consignors will make their decision relative to the basic commission rate.

Imagine a scenario wherein a seller is considering consigning to either Shop A or Shop B. Shop A charges a straight 50% commission. Shop B is the “new guy” in town and wants more consignments, so he charges a 45% commission plus fees. The impact of the fees on the consignor’s settlement proceeds is vague at the time the contract is signed. Here’s a simplified view of how the fees may impact the dealers and consignor’s money:

Shop A versus Shop B

Selling price: $100 X Commission: 45% = Gross commission: $45

PLUS: Buyer’s fee: $2, Item fee: $2, Credit card fee: (@3%) $3, Check fee: $1, and Access fee: $2 = Total fees: $10

Net to Dealer: $55

Net to consignor: $45

Effective commission rate: 55%

In this scenario, the dealer was able to bump his commission rate by 10 points by adding fees. Of course, fees will vary on almost every item, but the dealer net will always be higher with fees than with a commission-only contract.

Peeking at the Past Commission+Fee Model

All other matters being equal, the consignor would have made more money by consigning to the

dealer with the higher [50%] commission.

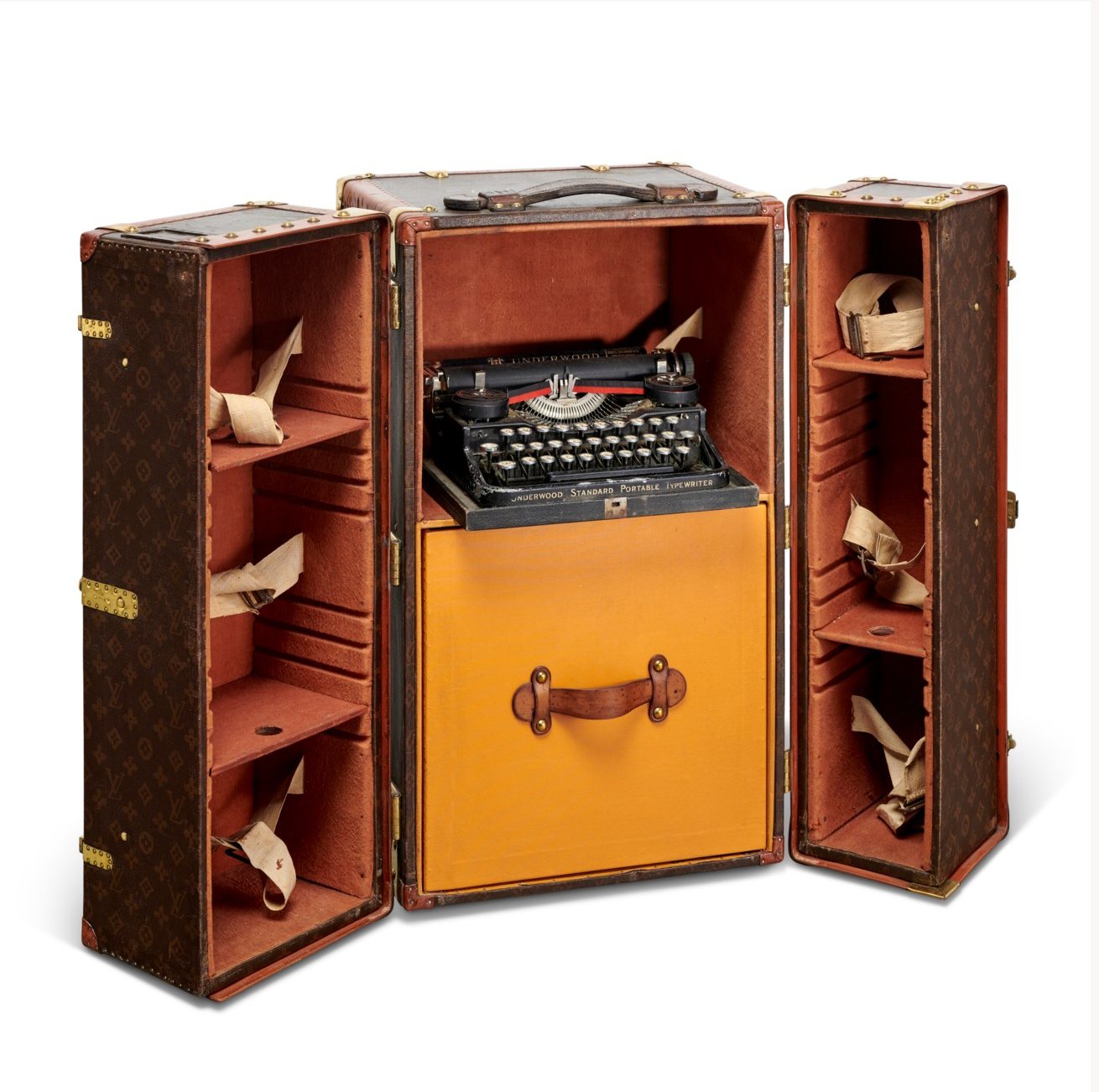

There’s no telling how far the “commission plus fees” model will go. In the mid-1970s, Christie’s and Sotheby’s introduced buyer’s premiums. The auction industry was surprised to learn that buyers were OK with having an extra 10 percent tacked on to their purchases. Over the next couple of decades, buyer’s premiums became a standard practice in the industry.

Since 1974, buyer’s premiums at top-tier auction houses have risen to 25 percent, and fees have stacked up quickly. Will this happen in the consignment business as well?

Consignment dealers who are “boxed in” by the financial limitations of fixed commission rate contracts must find a way to boost margins. To make sellers assume the entire burden of higher expenses is short-sighted, though.

A few options for “spreading the financial burden” might include:

— Increase the amount of owned inventory; higher margins can be achieved.

• Price merchandise at a healthy margin (that includes credit card fees) and offer a discount for paying by cash or check. This puts the credit burden where it belongs – with the buyers using plastic, rather than with the consignor.

— Charge sellers a daily “flooring” or “slotting” fee in order to display their items. This is a common practice in retail businesses; it is a major profit center for grocery stores and dry goods retailers (including Walmart).

• Referencing the fees addressed in McGonagle’s article, I would keep the buyer’s fee and item fee but drop the check and access fees altogether. In my opinion, the latter two fees are just insulting to consignors.

Closing Thougths

Estate goods will continue to flood the market for at least another decade. Competition for quality consignments will increase, and dealers will feel the pressure. Finding a consignment solution that works for all parties – dealers, consignors, and buyers – will provide a solid foundation for business growth.

Longtime columnist, writer, and author, Wayne Jordan is an antiques and collectibles expert, retired antique furniture and piano restorer, musician, shop owner, auctioneer, and appraiser. His passions are traveling and storytelling. He blogs at antiquestourism.com and brandbackstory.com.