The handmade antiques conundrum

An acquaintance of mine, visiting in the area for a short time, asked where she could go shopping for some genuine “handmade antiques.” She was referring specifically to furniture. I…

An acquaintance of mine, visiting in the area for a short time, asked where she could go shopping for some genuine “handmade antiques.” She was referring specifically to furniture. I guess that’s why she directed her question to me. I asked her to please define “handmade” and “antique” and I would be glad to direct her. Her answers touched off a debate that generated a lot more heat than light on both subjects. You are welcome to join the fray.

Her definition of handmade was “built without the use of machinery.” Her definition of antique was “more than 100 years old.” That seemed straightforward enough on the surface until I questioned her further on the definition of machinery. Her answer? “You know, power saws and stuff.” OK. And why 100 years on the definition of antique? “Because that’s what all the experts say.” After drawing several deep breaths to calm my rising blood pressure, I tried to enlighten my friend on both subjects.

'Machine made' vs 'not machine made'

Sometimes I find it useful to define what something is not rather than what something actually is. Accepting the premise that “not handmade” is the same as “machine made” and that “handmade” is “not machine made” is required for this line of thought.

My dictionary defines a machine as “a mechanical apparatus or contrivance; a device which transmits or modifies motion; an apparatus consisting of interrelated parts with separate functions which is used in the performance of some kind of work.”

The six elementary machines that we all learned in 8th grade physics are the wheel and axle, the pulley, the ramp, the wedge, the screw and the lever. No matter how simple or complex a piece of machinery becomes, all of the mechanical elements in it are based on one or more of these components.

That opens a whole new line of thought. My friend’s definition of handmade seemed to imply that for something to be truly handmade, machines must not be employed in its construction or assembly. She probably meant electrically powered machines but in the long run what is the difference between an electric saw, a steam-powered saw, a water-driven saw, a mule-powered saw or a hand-powered saw? Nothing but the source of power and efficiency of operation.

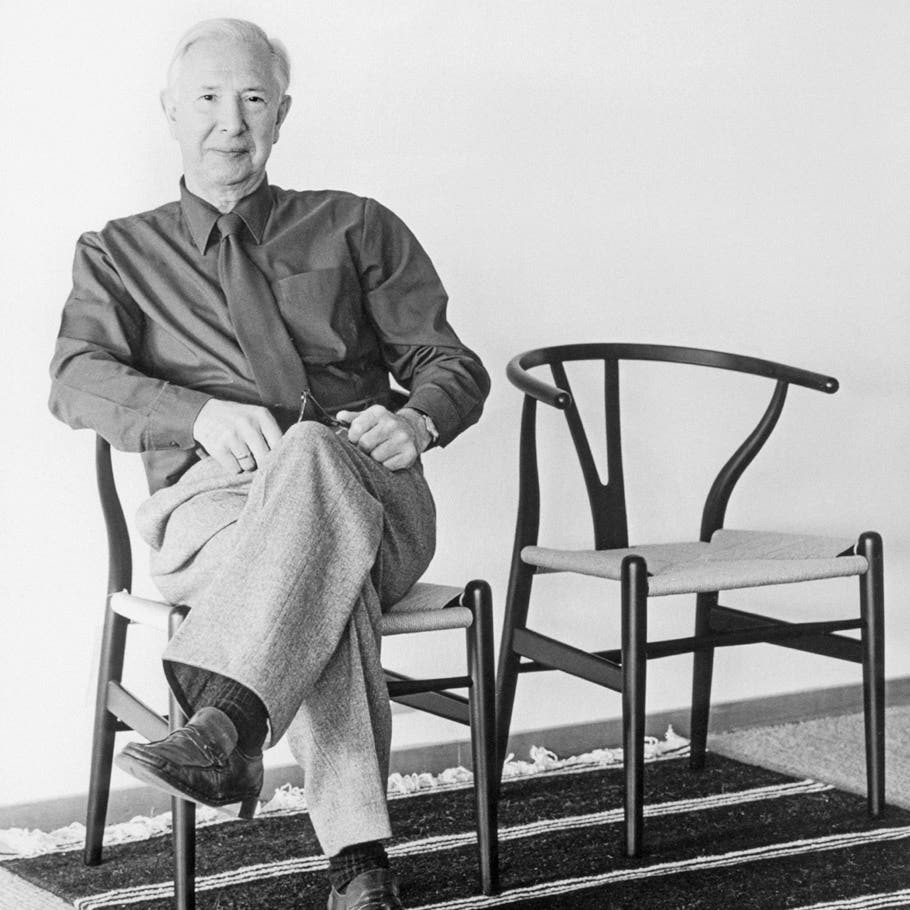

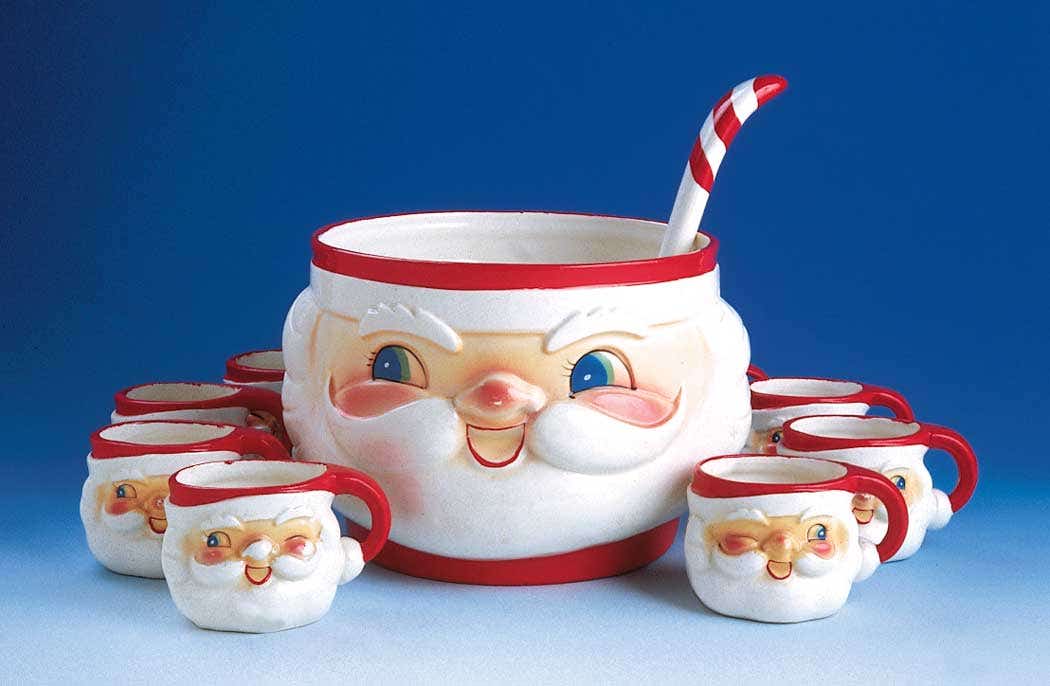

A pot thrown on a potter’s wheel is already using at least one type of machine, the wheel and axle, so what difference does it make if the wheel is foot powered or steam driven or if the kiln that fires the pot is wood fired or electric? The maker of an 18th century Windsor chair certainly employed several machines to construct and assemble the components. The legs and spindles were almost certainly turned on a foot-powered lathe, a machine by anyone’s definition, and the holes for the legs and spindles were bored using a drill composed of a wedge and a type of lever or screw — all elementary machines.

When you get right down to it, even something as simple as the ax used to fell the tree to harvest the lumber for the cabinet shop is a type of elementary machine, a wedge. And simple scissors are actually just opposing levers. In fact, about the only things I can think of that are truly handmade, without the use of any machinery, are mud pies and snowballs, but they don’t keep very well and have little chance of becoming antiques.

'Hand crafted' a better term

Perhaps a better term than “handmade” would be “hand crafted.” This implies the careful attention of a craftsman turning out a special product under his direct supervision, using his own acquired skills, no matter what tools or machinery are used. A craftsman cutting out Chippendale pierced splats with an electric scroll saw is no less skilled than one using a manual keyhole saw — just different skills applied to different machines to produce the same work.

In terms of furniture, the traditional methods of furniture construction are referred to as handmade, bench made and machine made. Handmade in this case usually refers to the lack of power tools but as we have seen, all tools (machines) use some type of power. Bench made more closely reflects the hand-crafted idea, with an artisan using modern tools to personally assemble a piece of work. This is the basis for many of the great pieces of Centennial furniture produced during the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th century and is still used in some high end factories such as the one owned by Kittinger in Buffalo, N.Y.

And finally there is the great evil referred to in a derogatory manner as “machine made.” But walk into any furniture factory in America, or anywhere else for that matter, and you will not see machines making furniture. You will see people using machinery (tools) to make furniture.

For furniture perhaps the definitions should be changed to “shop made,” indicating an individual craftsman in his own shop either working alone or with an apprentice or assistant, “bench made” as defined before and “factory made.”

But even that can be deceiving. “Factory” brings to mind the huge contemporary operations in North Carolina and Grand Rapids or the turn-of-the-century factories in New England and the Midwest. But furniture factories were the main method of production long before the 20th century.

Most of the great mid-19th century makers had factories where furniture was built on a more or less assembly line basis. Lambert Hitchcock was using the assembly line method in his three-story factory in Connecticut in the 1820s, 40 years before Henry Ford was even born. That factory was powered by a water wheel.

The renowned firm of Joseph Meeks & Sons had a multistory factory on Broad Street in New York when they published their famous broadside of models in the early 1830s. John Henry Belter had one of the largest factories in New York in the 1850s. Over the years, he imported hundreds of mostly German craftsmen to work in his factory and most of them, at least initially, lived in his dormitory-styled house. You can read their names in the 1850 census of Manhattan. The Herter brothers had a big operation up around Central Park later in the century, as did Pottier & Stymus. Prudent Mallard had a factory in New Orleans and George Henshaw and Mitchell & Rammelsberg had factories in Cincinnati.

So maybe the term “factory made” doesn’t quite give the correct sense of what we are trying to convey after all. In fact, none of these terms regarding the construction and assembly of furniture accurately describes the process of producing furniture. It’s like trying to navigate the ocean in the 15th century before the invention of the accurate, portable timepieces needed to calculate longitude. A coordinate on the map was missing; just as “factory made” makes no distinction between 1830 and 1980. And bench made, while most commonly associated with the early 20th century, is also a method still in use today.

The missing coordinate is time. This becomes particularly important around the turn of the 19th century. Before that, most furniture was, by definition, “shop made” although certainly not truly handmade as noted above. But with the advent of the larger metropolitan areas and increasing population, the one-man band furniture maker gave way to early factories so a distinction must be made. Unarguably there are important differences between furniture made in an 1830 factory and that made in a 1980 factory so we should be more specific.

How about the use of such terms as “factory made in the mid-19th century” or “factory made in the early 20th century?” That narrows what we are talking about by a great margin. The same with “shop made.” “Shop made in the late 18th century” certainly provides a clear separation from “shop made in the 20th century,” which some custom furniture certainly is. The same time frame distinctions apply to bench made and hand crafted. And anyone familiar with the history of furniture styles, technology and construction will know immediately what you are talking about. No more of this touchy/feely stuff about handmade. Get specific in the language and get results.

Now what about antique? That’s for next time.

With more than 30 in the antique furniture business, Fred Taylor is a household name when it comes to the practical methods of identifying older and antique furniture: construction techniques; construction materials; and style.