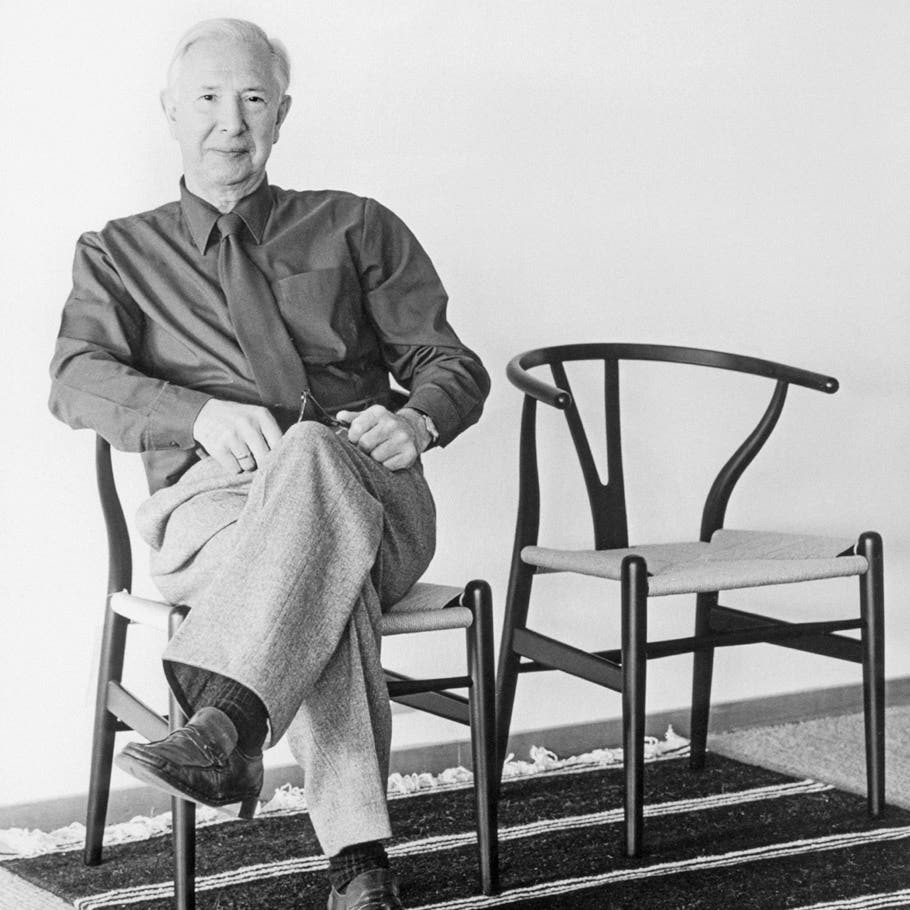

George Nakashima’s Kinship with Trees Shines in His Furniture

During his career, the renowned mid-century woodworker produced some of the most original and influential designs of the post-war era.

George Nakashima believed that each tree had its own soul, and his mission was to find its “living spirit” and give it a second life. During his illustrious career as America’s most important contemporary woodworker, he accomplished that and then some.

Working out of his compound in rural New Hope, Pennsylvania, Nakashima produced some of the most original and influential furniture designs of the post-war era. In striving to realize a tree’s true potential, Nakashima chose solid wood over veneers and designed his furniture to highlight the inherent beauty of the wood, such as the form and grain: his tables often feature natural fissures, knot holes and freeform edges.

His internationally renowned work always sells well at auction — and usually for thousands above the high estimates — and has been collected by such celebrities as Steven Spielberg, Brad Pitt, Julianne Moore and fashion designer Narciso Rodriguez. In 2002, Diane von Furstenberg bought a 14-foot-long Nakashima dining table for $130,500 at a Phillips, de Pury & Luxembourg auction, which was the world auction record for him at the time, according to The Chicago Tribune. Some of his pieces have now sold for even more.

But Nakashima had a long journey before he arrived at the philosophy for which his designs became sought after in mid-century America.

The Japanese-American Nakashima was born on May 24, 1905 in Spokane, Washington, to parents who had only recently immigrated from Japan and met on the ship. Both were descended from samurai, the traditional warrior class of feudal Japan. As a child, he was a member of the Boy Scouts and eventually earned the rank of Eagle Scout. The group’s hikes and camping trips are likely what instilled in him a love of trees and nature that continued throughout his life.

“A tree is our most intimate contact with nature.” — George Nakashima

Nakashima attended the University of Washington and studied forestry before switching gears to train as an architect at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, earning a master’s degree in 1930. The forestry classes may explain his affinity for wood and ability to select and grade fine lumber, but it seems to be deeper than that. “The love of wood is in my genes,” he once said. “Japanese culture is a wood culture.”

After his studies, Nakashima sold his car and purchased a steamship ticket to travel around the world, spending time in France, North Africa and Japan. This travel contributed to his vast knowledge of design, materials and techniques, and shaped his signature style. Yoga was also a big influence. In 1934, he joined the architecture firm of Antonin Raymond, a protégé of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Raymond sent Nakashima to Pondicherry, India, to supervise the construction of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. While there, Nakashima became a disciple of the guru Sri Aurobindo and learned Integral Yoga, which promotes a restful body, a peaceful mind and a useful life. This practice had a lasting impact on his philosophy as a designer.

Time in an internment camp also had a profound effect on Nakashima and his work. In 1942, he, his wife, Marion, and newborn daughter, Mira, were forced into a camp in Idaho. Ten internment camps were established around the country during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, would be incarcerated in the isolated camps; 120,000 Japanese-Americans were held.

While in Idaho, he met the master Issei carpenter Gentaro Hikogawa, who was trained in traditional Japanese carpentry. Under Hikogawa’s guidance, Nakashima learned to master traditional Japanese hand tools and many woodworking techniques.

In 1943, Antonin Raymond managed to secure a release for Nakashima and his family, by employing him on his farm in New Hope. It was there that Nakashima opened his first workshop, and began his long career as a woodworker, drawing not only on what he learned from Hikogawa, but also on American vernacular forms, such as the Windsor chair.

Nakashima was soon designing for manufacturers Knoll and Widdicomb-Mueller, which brought his creations to a wider audience. He also continued his private commissions and the studio grew to a dozen artisans. The quality of his furniture also improved as he gained greater access to rare woods from around the world.

Nakashima embraced the unique qualities of wood — cracks, holes, other imperfections. For him, they revealed the “soul of the tree.” He believed that the individuality of the wood should be celebrated, and it was the role of the craftsman to bring it out. His integration of butterfly key joints became a prominent feature in his later work, further emphasizing the natural beauty of the wood grain and burl. This simple joinery technique has come to be recognized as a trademark of Nakashima’s philosophy — a minimal intervention in the original forms of the wood. He explains his philosophy best.

“In Japanese, kodama, ‘the spirit of a tree,’ refers to a feeling of special kinship with the heart of a tree. It is our deepest respect for the tree … that we may offer the tree a second life.” — George Nakashima

Another important element in identifying a Nakashima piece is the existence of a sketch, drawing or other record from the artist or his studio. Since the studio still produces new works, pieces completed posthumously are all signed and dated. He formed a close working relationship with all his clients, and the wooden boards he used were often handpicked for the individual and signed with their name in ink underneath, connecting each work to a specific time and place.

Nakashima won many awards, most notably the Third Order of the Sacred Treasure, an honor bestowed by the emperor of Japan and the Japanese government in 1983.

His home, studio and workshop, which is on twelve acres and has twenty-one buildings designed by him, was designated a United States National Historic Landmark and a World Monument in 2014. Today the estate houses George Nakashima Woodworkers, creating bespoke, handcrafted furniture under the leadership of Mira, also an architect and designer, who worked closely with her father and oversees the production of his designs. His son, Kevin, who passed away in 2020, was a longtime board member of the Nakashima Foundation for Peace.

"Each flitch, each board, each plank can have only one ideal use. The woodworker, applying a thousand skills, must find that ideal use and then shape the wood to realize its true potential." — George Nakashima

The prices that Nakashima’s pieces now command have rocketed, and large works can fetch upward of $100,000 and more on the secondary market. There has been a recent surge in sales in Europe, too.

Two June auctions by Freeman’s Auctions of Philadelphia and Wright of Chicago, houses known for being experts on Nakashima’s work, saw a number of pieces soar above estimates.

Wright said it was early to recognize the importance of Nakashima’s oeuvre and since its first auction in 2000, works by the master craftsman have appeared in almost every auction, with sales totaling over $12 million. Wright has handled more than 1,000 works by Nakashima, with 80 percent of lots sold exceeding high estimates — the accompanying results setting new benchmark prices for the artist and demonstrating buyers’ confidence in the auction house.

At Wright’s June 10 sale, of the 21 Nakashima pieces sold, 19 items blew past their high estimates by thousands of dollars. Highlights include a Kent Hall floor lamp of walnut burl, walnut and holly, that sold for $62,500 against a high estimate of $22,000; a radio cabinet of American black walnut that sold for $27,500 against a high estimate of $20,000; and a single pedestal desk of American black walnut that also sold for $27,500 against a high estimate of $14,000. Wright also sold several pieces by Mira, including a Kornblut cabinet of East Indian laurel and Wych elm burl, for $12,500 against a high estimate of $7,000.

Freeman’s has sold hundreds of Nakashima pieces, including nearly 70 in 2020, and the auction house said the Select Design sale on June 8 emphasized this reputation for careful stewardship of his furniture. An auction highlight was an exceptional 1961 Conoid desk, in which a characteristic asymmetrical design is rendered in English walnut, American black walnut, rosewood, and hickory; it sold for $75,600.

Another highlight was a special Minguren I coffee table, featuring a striking oval table top made of Oregon myrtle and American black walnut — referencing Nakashima’s upbringing in the Pacific Northwest, but constructed in his longtime Pennsylvania studio. It sold for $37,800.

“The results clearly show Freeman’s ability to showcase works by George Nakashima, underscoring the depth of the Nakashima market both in the US and abroad," said Tim Andreadis, head of Freeman’s 20th Century and Contemporary Design Department. "We were pleased to see many new and younger bidders participate in the sale, many seeking to acquire their first work by the Pennsylvania woodworker.”

Nakashima passed away in 1990, and his family and a team of woodworkers have been working to maintain his legacy ever since. Mira and her cousin, TV producer John Terry Nakashima, completed a documentary in 2020, George Nakashima, Woodworker, which explores his indelible legacy. It features archive footage of Nakashima and interviews with family members, woodworkers and design critics, whose testimonies are woven together to explore his life and philosophy. The film gives the chance to experience the designer’s life journey and understand his approach to woodworking that he detailed in his 1981 book, The Soul of a Tree: A Master Woodworker's Reflections. The documentary can be purchased or streamed at www.nakashimadocumentary.com.

“There’s an elegance, there’s a grace, there’s a unity. It’s not contrived, it’s not decorated — it’s pared down to the simplest form it can possibly take,” said Mira of the enduring appeal of her father’s work.

“George avoided calling himself a designer or an artist. He said they’re ego-based labels. He only agreed to the term woodworker,” said John Terry.

You can read more about George Nakashima and see more work at nakashimawoodworkers.com.