Stories Cast on Stove Plates

Pennsylvania Germans engraved lore, ornate designs on their stove plates

When German immigrants left their homeland to make the treacherous journey across the Atlantic to America in the early 18th century, the precious cargo many took with them were their iron stoves.

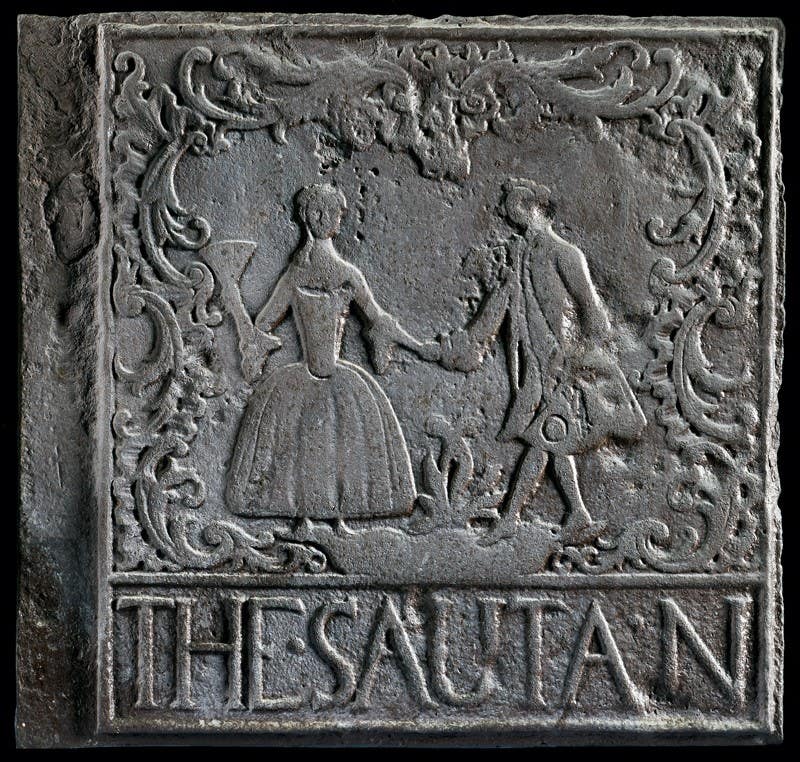

The Germans, who settled in Pennsylvania, used jamb stoves with ornamental stove plates that were ornately engraved with historic lore and low relief designs that often included secular mottoes, biblical inscriptions, human characters and pictorial designs. They looked upon these iron stoves as an essential component to their daily living.

These stoves were also a valuable commodity. David Seibt, a recent arrival to Germantown, penned a letter dated December 20, 1734, to his brother, who was also planning to come to America, and said: “If you should come, bring with you an iron stove, too. They are dear here, are better than the earthen ones that do not last so long, and are very high priced…”

With the typical stoves weighing between 320 and 450 pounds, it was difficult to quantify how many were carried across the Atlantic Ocean to America, but the knowledge of constructing cast iron stoves carried within the immigrants was precious in itself.

During the Colonial era, cooking was done in the fireplace, not on a cast iron stove. No matter if it was a grand house with its kitchen set apart in a detached building or the simplest log structure, food was cooked within the open hearth. The stoves were not designed for baking and were instead used to heat homes.

During most of the 18th century, most houses followed a similar foot-print. Usually small in size and made of logs, they had a chimney that rose up through the middle of the house, most often constructed of stone found in the area. The base of this chimney opened the cooking fireplace. The kitchen, narrow in width, was located on the northern and western sides of the house to offset the cold coming from those directions. On the back wall of most every kitchen fireplace was cut a small curved hole about eighteen inches in width and height. Known as an “offenloch,” (“stove hole”), this hole opened into the “schtube” or stove room. This small room was on the southern and eastern sides of the house, and warmed by a five-plate iron stove.

The stoves were constructed using five heavy iron rectangular plates, each one about two feet by two feet square. Each thick plate weighed in excess of fifty pounds. The bottom plate sat flush with the bottom of the stove hole and so formed the floor of the stove upon which the wood fire burned. These plates were bolted together and held up on legs thirteen to fifteen inches from the floor. Firewood was placed in the stove from the kitchen. Smoke went back out through the stove hole and up the central chimney. Since the stove was fueled from the kitchen, there was no stove door or smoke pipe. The five-plate stoves were open in the back and mortared into the wall behind a fireplace. A vent from the fireplace allowed hot air to travel into the stove and heat the plates; the heat from the stove then radiated heat into the room. The stoves had been used in this manner since the middle of the 16th century in European homes.

Invariably, some stoves suffered damage and had to be repaired, which often meant replacing plates. Records of Pennsylvania’s oldest blast furnaces show that the earliest stove plates made in Pennsylvania was in 1726; the first five-plate American-made stove was completed in 1738.

With the advent of American-made stove plates in 1750, the designs seemed to venture from the biblical and human characters of German plates to more bucolic themes: floral designs, especially tulips, sheaves of wheat and details of hearts, stars, and medallions in relief. European architectural designs were also in favor.

Stove plates command good prices. A plate from Pennsylvania, inscribed “Temptation of Joseph,” sold for $2,812 on October, 30, 2019, at NYE Co. Auctioneers. A Shakespeare-inspired two-piece plate set, circa 1899, cast with the three witches of “Macbeth” and the verse, “Double, double, toil and trouble, fire, burn and cauldron bubble,” was offered on 1stDibs.com for $850 (reduced from $3,600). A cast iron plate depicting the marriage feast at Cana in Galilee (maker unknown) and circa 1600 is valued by Canterbury Auction Galleries between $2,000-$2,600. Others have sold between $100 to $1,500.

Pennsylvania Germans did not hold a monopoly on the market on stoves; other European nations and America produced these five-, six- and even ten-plate stoves. On the auction market, a Swedish baroque cast iron stove plate is offered for sale by Eron Johnson Antiques for $1,350. An American cast iron stove plate, circa 1835-45, is for sale at Susquehanna Antique Company for a reduced price of $350. An early stove plate thought to be of English origin and dated 1730-40 is priced at $395.

As with what happens with most things, the use of the German stoves fell out of fashion, the main reason being that the Colonists favored other methods of heating their homes. The last year that cast iron stove plates were manufactured in Pennsylvania’s furnaces was 1794. In the years following, many stoves were disassembled and the individual stove plates found new life, recycled for other purposes. In the early 20th century, Dr. Henry Mercer, an early collector of stove plates, launched a study of them. He discovered that they were recycled throughout Pennsylvania and being used for a plethora of odd jobs including cistern caps, stepping stones, patches, and, most commonly, as firebacks.

Sources

Beckerdite, Luke, “Pattern Carving in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia”: chipstone.org.

Mercer, Henry Chapman, “The Bible in Iron,” The Bucks County Historical Society, 1914.

Mercer, Henry Chapman, “The Decorated Stove Plates of the Pennsylvania Germans,” 1899.

Morehouse, Rebecca, MAC Lab State Curator, “Scripture in Iron: Pennsylvania German Stove Plates from Antietam Furnace,” Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, April 2016: jefpat.maryland.gov.

“Our Heritage,” the Historic Manheim Preservation Foundation, Inc. Volume 4, Number 1, January 2006.

Wood, Robert, The Historian, “The Historian: The Evolution of the Cooke Stove,” Part I, March 21, 2013: berksmontnews.com.