The Big Switch: A sudden surge in lighting

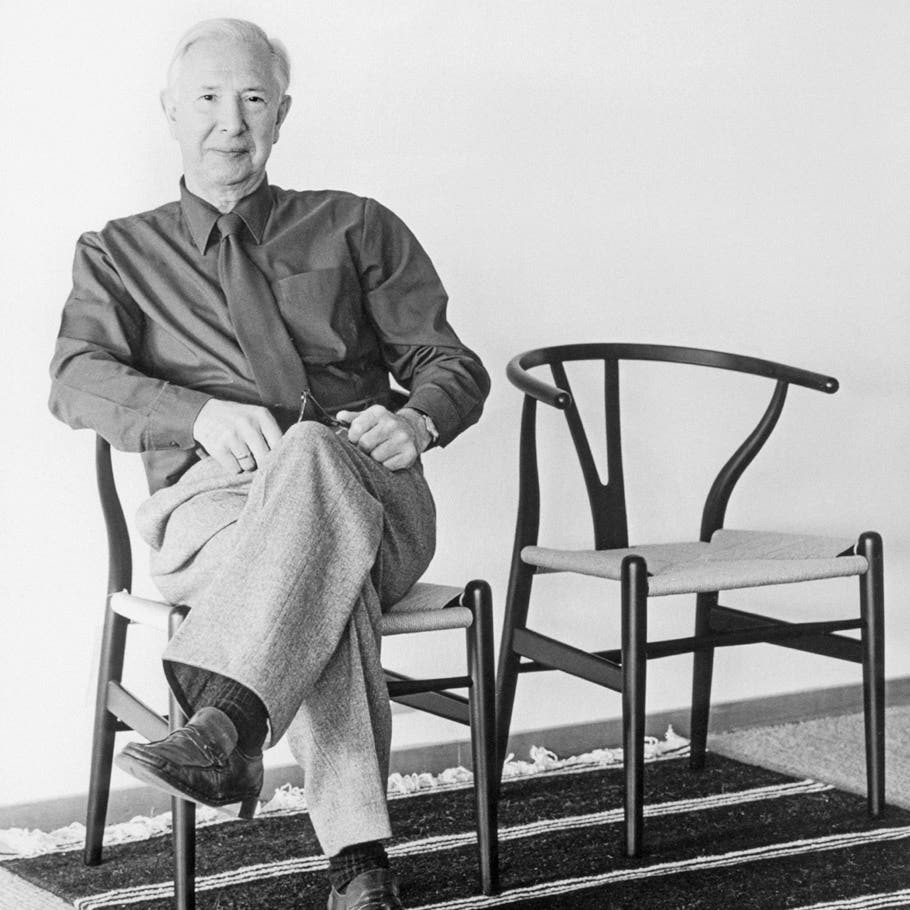

Dr. Anthony J. Cavo, a regular contributor of Antique Trader, admits that lamps aren’t his ‘thing,’ and yet among his latest acquisitions are 11 lighting devices. Can you relate to this collecting experience? Learn more about what drew Anthony to these lamps.

Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

The characteristics of collecting change, not only in general but with the individual as well. Lamps are not my thing; however, my recent finds have all been lamps. I bought 11 lamps in the past three weeks. Who needs 11 lamps besides someone who collects lamps or lives in a very big, very dark house? It often happens this way. You buy one of something then suddenly it seems you are finding that something everywhere. Perhaps that something has always been around but your first purchase sensitizes you and you are suddenly more aware and appreciative of that item than you had been.

Immerse Thy Self

When I buy something old that is new to me, I investigate. If it is a lamp, I read about lamps in general then about that lamp specifically and I always learn a great deal. Once I learn about an item, I come to understand and value it then find myself looking for more.

In late February, I came across a super Bradley & Hubbard vase lamp with a cast iron stand and large burnt umber color base. The lamp is 22 inches tall (not including the stack) with a circumference of 34 inches. The cast iron handles are in the form of a plumed knight’s head. It has a milk glass shade with an ornately pieced brass veil overlay and dates to the 1890s. A lamp such as this, in age-appropriate, excellent condition, could sell in the $700 range.

Bradley & Hubbard Mfg. Co., Meriden, Connecticut, produced high quality products from 1852 until 1940 and made some of the most beautiful, affordable lamps of their time.

Shedding Light On the Topic of Lighting

In reading about B&H, I learned some illuminating facts (pun intended). Bradley & Hubbard initially had two other partners from 1852 to 1854; they were the Hatch brothers. In 1854, the Hatch brothers sold their interest to B&H. Although most people associate B&H with lamps, they originally manufactured clocks and did not begin making lamps until 1868. Bradley, Hubbard, and Hatch, and later Bradley & Hubbard, made clock cases but used clock works from other companies. Some of the most valuable cast iron clock cases are the figural cased examples made by B&H. Many clocks from this time, if they were marked, typically had a paper label.

In addition to lamps of all types, B&H manufactured many household goods. They produced doorstops, desk sets, clocks, fireplace accessories, match safes, bookends, lamp tables, heaters, oil stoves, candlesticks, brass trays, sewing machines, call bells, flags, skirt hoops, and spring-loaded measuring tapes. They also produced the popular nickel-plated Rayo lamps for the Standard Oil Company.

Prior to 1859, whale oil fueled most lamps but in 1859, oil was discovered in Pennsylvania and by 1871, kerosene had replaced whale oil as lamp fuel. B&H took great advantage of this discovery and by 1875 B&H had 33 patents on a variety of lamp parts; in total, B&H secured over 200 patents. In 1897, the firm began to produce gasoliers and electroliers. B&H never registered a trademark and had a number of different marks: B&H in a circle, B&H in an oval, B&H with printer’s flowers (Aldus leaf) above and below, B&H in a wreath, but perhaps the best-known mark is the Aladdin’s lamp within a triangle bearing the “Bradley & Hubbard” names.

It Begins With One

When you think about B&H, remember there is more to B&H than lighting; the next time you examine

a quality piece of cast iron, brass, or bronze, a bookend, a clock, or fireplace accessories look for the mark of quality – look for B&H.

On the same day, I discovered my B&H lamp, I purchased two other lamps. One is a B&H with a bronze base and the other an ornate, large vase lamp manufactured by the Edward Miller Company.

The Miller lamp has a red base fitted in a cast iron stand with winged lions for handles. It is 22 inches tall (without the stack) and 34 inches in circumference with bent green glass panels. There is a definite Arts & Crafts feel to the shade and the deep green of the shade contrasts strikingly to the red glass and cast iron base. This lamp, in age-appropriate, excellent condition with original parts and shade, is valued in the $1,200 range.

Edward Miller & Co's Impact

Edward Miller & Company (1844-1924), also in Meriden, Connecticut, is known primarily for its lamps but also made household goods such as teapots and oil heaters. Mr. Miller did not start the business, but took it over in 1845. It became Edward Miller & Company in 1866 and in 1924, the business transferred its assets to The Miller Company (1924-2000). Edward Miller & Company had showrooms in New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and San Francisco. They exhibited their lamps at and won awards from many prestigious expositions such as the Centennial Exposition of 1876, Melbourne International Exhibition in 1881, and the Pan American Exposition in 1901. The Corning Museum of Glass, the Connecticut Historical Society and the Henry Ford Museum include Miller’s designs in their collections.

By the turn of the century, Miller & Co. had over 2,000 lamp designs. They produced the “Rochester” line of lamps for the Rochester Lamp Company from 1884 to 1892, hence the similarity between many Miller and Rochester lamps.

Name Aids in Determinig Age

The name “Rochester Lamp” became “New Rochester Lamp” in 1892 after Miller & Co. no longer made them. (This is a useful bit of information to aid in dating your Rochester and New Rochester lamps.) If you collect or deal in antiques there is no doubt you have come across a product of Edward Miller & Company and may even recognize some of the many lamps the company produced: Juno Lamp, Empress Lamp, Mill Lamp, Non-Explosive Lamp, Gaskill Lamp, The New Juno Lamp, Meteor Lamp, and the New Vestal Lamp. The company also made lamp parts like burners and screw on caps that bore their name, but a lamp is not considered a Miller Lamp unless the name is stamped on the font.

Edward Miller & Company continued to thrive as they adapted to changes in the world of lighting from kerosene to gas to electricity. Edward Miller with his design for a tungsten filament lamp improved the early carbon filament lamp designed by Thomas Edison. The company continued to establish itself with early achievements in mercury vapour lamps and fluorescent lighting. For additional information about the Edward Miller Co. I would recommend the following sites: https://bit.ly/2H6Kl0j and https://bit.ly/2Hzplyu, with the latter site being especially useful with tips on cleaning and restoring Miller Lamps as well as hosting diagrams and many photos of the different lamp styles plus an informative glossary.

Lamps, Lamps and More Lamps

My lamp finds were not limited to kerosene burning lamps. I also picked up two jeweler’s lamps, one 19th century and one early 20th century, a bronze lamp with a multi-colored slag glass shade, a space-ship lamp from the 1930s, a “modern” copper lamp from the 1930s, three sacristy lamps, and a super Dazor Model 1000 Airplane Wing Desk Lamp from the 1950s.

The 19th century alcohol fueled jeweler’s or singeing lamp, patented 1880 and 1893 by John H. Purdy of Chicago, is ingenious in its simplicity. It consists of two pieces: the bulbous glass font sits in a bowl-shaped base and can swivel in all directions and in a 180-degree side-to-side arc. This enabled the jeweler to position the flame in many directions as well as control the distance of the flame from the object on which he worked. The lamp was also used to melt wax and apply solder.

I find the use of these lamps by barbers for singeing hair rather than cutting to be the most interesting use. The globe construction fit easily into the barber’s hand and enabled him to direct the flame. These lamps, manufactured in different colors, included clear, amber, green and blue glass. This particular lamp is missing the cap, or snuffer, which should hang by a chain. Although simple in design, they have an aesthetic charm as do many spherically shaped objects, and can sell in the $75 to $125 range, depending on color, condition and presence of the cap.

Learning About Industrial Age Through Lamps

After purchasing Purdy’s alcohol burning, jeweler’s/singeing lamp I began to research jeweler’s

lamps and as a result I was able to identify and buy another jeweler’s lamp with a completely different appearance and powered by electricity. Had I not read about lamps – and jeweler’s lamps in particular – I would never have identified this lamp as a jeweler’s lamp. This lamp, by the Faries Manufacturing Company, is copper and nickel. The copper dome, mounted on a ball-socket, swivels in many directions so the light can aim in a specific direction. Art Deco lamps like this, meant for professional or industrial use are now referred to as “Machine Age Modern.” The term “Machine Age Modern” refers to a period that peaked between World War I and World War II; however, the exact period is from the late 1880s to the early 1940s.

The Faries Manufacturing Company of Decatur, Illinois, produced innovative, adjustable electric lamps and fixtures for both industrial and residential use. Robert Faries founded the company in 1894. During the early 20th century, Faries lamps were used extensively in medical and dental offices. Many lamp and lighting collectors consider Faries Company lamps, which are not easily found, the “Holy Grail” of industrial lighting. This particular lamp is in very good, working condition and is valued in the $180 to $220 range.

Eying Art Deco

They say, “When it rains it pours” and without getting into the nuances and characteristics of Morton Salt, I have to agree. As I discussed earlier it seems that when you encounter one type of item you tend to discover another or even a few more in rapid succession. Hence, these two Art Deco lamps, which I discovered in two successive tag sales I encountered incidentally while driving to a friend’s house. The first is a copper desk lamp and the second a chrome and glass desk lamp, both reminiscent of early 20th century impressions of space ships. Neither lamp bears a maker’s name, but their style enables them to hold their own in terms of desirability and value. The inside of the two-piece dome of the copper lamp is silvered to maximize reflection, light also passes through the horizontal line between the upper and lower halves of the dome.

The dome on the chrome lamp is pierced with crosses and stars through which the light shines brightly when the lamp is lit giving it an astral effect. With a low wattage bulb, the chrome lamp might serve as a night light. Today lamps in this style are described as “Atomic Age” lamps; however, these lamps predate the atomic age, which began with the detonation of the first nuclear bomb at the close of World War II. Aesthetically attractive lamps such as these need not have a maker’s name to bolster their value. I have seen the copper lamp in a combination of copper and chrome, which is much more desirable, sell for $950.

The value on this copper lamp, however, falls in the $120 to $140 range. The chrome spaceship lamp is in the $140 range.

Tricky Dating Circumstance

There is no doubt that I became sensitized to lamps and within a couple of days I purchased three more. The first two are early 20th century lamps neither of which bears a manufacturer’s name. A maker’s name is not a requirement in dating an object. These lamps date to at least the first 10 years of the 20th century; everything about them supports such a date of manufacture. The warm, rich, uniform patination on the bronze base and the heat cap/aperture-ring of the slag glass lamp can be achieved only by the passage of a hundred years.

Furthermore, the pierced bronze socket cluster, acorn-tipped pull chains, silk-wrapped cord and shape of the base and shade define this piece as dating anywhere from 1900 to 1915. Silk-wrapped cords were in use from 1900 to 1915 when the fabric covering was switched to cotton and rayon. The wires in the cord set are separate, as was seen prior to 1915. Pull chain light switches were first used in 1896 when they were patented by Harvey Hubbell. The Hubbell acorn pull chain was used from 1900 to 1910, which gives immense support to the production date of 1900 to 1910.

The Art Nouveau end-of-day boudoir lamp has a white glass background into which has been laid irregularly shaped pieces of marbleized orange and green glass; it is probably Czechoslovakian in origin. The base of the lamp bears a ground pontil mark and the socket is a pull chain Hubbell. The lamp was rewired during the early 1920s and an in-line “Bakelite” switch supplanted the Hubbell pull chain.

Understand Parts, Understand Lamps

When investigating items you must account for the presence or absence of parts. In this case had I used the Eagle Bakelite in-line switch to date the lamp I would have incorrectly dated it to the 1920s since the Eagle Electric Manufacturing Company was not founded until 1920. However, I had to account for the older, pull-chain Hubbell socket that houses the bulb. Why is there a socket that predates the switch and why is there a channel in the socket for a pull chain yet no pull chain, but rather an in-line switch? The answer, of course, it that it retained the original socket minus the pull chain when rewired sometime in the 1920s.

When dating lamps it is imperative that you follow every lead. This lamp is probably worth between $250 and $300, although not a price for which I would part with it. Antique collectors are permitted to be impractical on occasion. We have all encountered that question: What is it worth and for what amount would I sell it? If you’re like me the spread is wide.

The last, and newest of my recent finds is a silver-grey, airplane-wing Dazor Model 1000 desk lamp from the 1950s. This desk lamp has quickly become one of my favorites. It has a sleek design evocative of the wings of a mid-century commercial airplane. The double gooseneck lamp is adjustable and can aim the light down, forward or up; it takes fluorescent bulbs.

Mid-Century Investment Gain

The modern push-button power switches are red and black indicating on and off respectively; it is in almost mint condition and sat on the same desk since first purchased more than 60 years ago. They were produced in silver-grey or bronze with the silver-grey commanding a higher price today. In good condition, these lamps can sell in the $75 to $90 range. In excellent condition, they can bring $125 or slightly more, depending on the venue. Those in need of repair or with a worn or damaged finish can sell in the $40 to $45 range.

I learned a great deal about lamps by simply becoming the owner of a few. I hope I’ve passed along some useful information and “brightened” your day in the bargain.

Now, go scouting for lamps and remember that reading keeps you “current” in terms of information. Jokes like these let you know why comedy is not my thing, and why I shouldn’t “switch” careers.

Thanks for reading.

If you like what you've read here, we invite you to check out the Antique Trader Antiques & Collectibles 2018 Price Guide.

Within this go-to guide you'll find more than 150 categories (including sub-categories of glass and ceramics), as well as an extensive lighting and lamps section.