Santa Still Sleighs Us: The centuries-old evolution of St. Nicholas

The Santa Claus we all know and love today — the white-bearded and rosy-cheeked grandfatherly man, trademark red suit trimmed with white fur, a sleigh filled with toys — has…

The Santa Claus we all know and love today — the white-bearded and rosy-cheeked grandfatherly man, trademark red suit trimmed with white fur, a sleigh filled with toys — has morphed through a variety of looks over the centuries.

From the description given in Clement Moore’s A Visit from St Nicholas in 1822 (“chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf”) through the vision of artist Thomas Nast (the current image is based on his illustration) and later Norman Rockwell, St. Nick gradually shed his various guises and became the jolly red-suited Santa we know now.

This is a little pictorial guide of his evolvement through the ages.

13th century

The name Santa Claus has roots in the Dutch name for St. Nicholas — Sinterklaas (an abbreviation of Sint Nikolaas). St. Nicholas was a historic 4th-century Greek saint, who was known as a secret gift-giver. He would put coins in the shoes left out for him, and was also famous for presenting the three impoverished daughters of a pious Christian with dowries so that they would not have to become prostitutes.

Being the patron saint of children, St. Nicholas has long been associated with giving gifts to kids and has other parallels to the modern-day Santa. In his Dutch form of Sinterklaas, he was imagined to carry a staff and ride above the rooftops on a huge white horse. He also had helpers who listened at chimneys to hear if children were being naughty or nice.

Although in Europe the feast of St. Nicholas is typically on December 6 and was popular throughout the middle ages, the reformation in the 16th century caused the celebration to die out in most Protestant countries, apart from Holland, where the celebration of Sinterklaas lived on.

17th century

Another important contribution to the image of Santa Claus was the phenomenon of Father Christmas — a traditional figure in English folklore. He typically represented the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, but was not associated with either children or gift giving.

The earliest English examples of the personification of Christmas are thought to be from a 15th century carol that refers to a “Sire Christmas.” The picture of Father Christmas featured at right is from Josiah King’s The Examination and Tryal of Father Christmas (1686), published shortly after Christmas was reinstated as a holy day in England after being banned in post Civil War England as a symbol of “Catholic superstition and godless self-indulgence.”

1810

Although America’s East Coast was full of Dutch settlers, it was not until the early 19th century that the figure of “Sinterklaas” made his way properly across the Atlantic and became an American-ized Santa Claus.

Following the Revolutionary War, the already heavily Dutch-influenced New York City (formerly named New Amsterdam) saw a new surge of interest in Dutch customs, and with them St. Nicholas.

In 1804, John Pintard, an influential patriot and antiquarian, founded the New York Historical Society and promoted St. Nicholas as patron saint of both the society and city. On December 6, 1810, the society hosted its first St. Nicholas anniversary dinner. Pintard commissioned artist Alexander Anderson to draw an image of the saint to be handed out at the dinner. In Anderson’s portrayal, St. Nicholas was still shown as a religious figure, but he was also putting gifts in stockings hung by the fireside to reward goodness. While “St. Nicholas Day” never caught on as Pintard wanted, Anderson’s image of “Sancte Claus” did.

A year before the New York Historical Society’s feast, author Washington Irving had written about Santa in his satirical fiction, Knickerbocker’s History of New York, describing a jolly St. Nicholas character, as opposed to the saintly bishop of yesteryear — and one who flew in a sleigh pulled by reindeer and delivered presents down chimneys.

The next key step to securing the image of Santa Claus was the 1822 poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” written by Clement Moore, which was later known as “The Night Before Christmas.” Moore drew upon Irving’s description and Pintard’s New Amsterdam tradition and added some Norse God Odin-like elements from German and Norse legends to create the all-winking, sleigh-riding Saint and also the names for his flying reindeer.

1863

As time went by, more details were added to the Santa Claus legend. Cartoonist Thomas Nast established the bounds for Santa Claus’ current look with an initial illustration in an 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, as part of a large illustration titled, A Christmas Furlough.

In later Nast drawings, a home at the North Pole was added, as was the workshop for building toys and a large book filled with the names of children who had been naughty or nice.

1864

Although Nast had gotten the reindeer, sleigh and other details down to a tee, the famous red suit was still yet to be set. Over the decades, Santa’s clothing was depicted in a variety of colors such as blue, green and yellow, as pictured in the 1864 edition of Moore’s “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

1868

In a 1868 advertisement for Santa Claus Sugar Plums, Santa’s jacket is red with green trim and his hat is green with red trim. His red pants are missing, though, and, in fact, he seems to not be wearing any pants.

1881

In a later 1881 illustration by Nast titled, Merry Old Santa, the modern Santa character really begins to take shape. Present is the big jolly belly and finally the iconic red suit.

1902

L. Frank Baum’s The Life and Adventures Of Santa Claus, with its elaborations and much added detail, went a long way to popularizing the legend of St. Nick. However, on the cover of the first edition of his book featured, the red of Santa’s whole suit is still yet to be “mandatory.” On the cover of the book, Santa is wearing red pants and boots, but a black jacket that looks like it’s trimmed in leopard fur.

The Christmas 1902 cover illustration for Puck, by Australian artist Frank A. Nankivell, shows perhaps for the first time a depcition of Santa that is indistinguishable from that of the present day.

1913

Illustrator Norman Rockwell, with his many depictions throughout the 1920s, was a key player in cementing Santa’s modern look. The December 1913 cover of Boy’s Life shows an early illustration of his from before the First World War.

1914

The spread of the Santa legend had reached far wider than just Europe and America, as a Japanese illustration from 1914 shows. In it, Santa is wearing his iconic red suit and is about to fill stockings hung on the fireplace mantle with gifts.

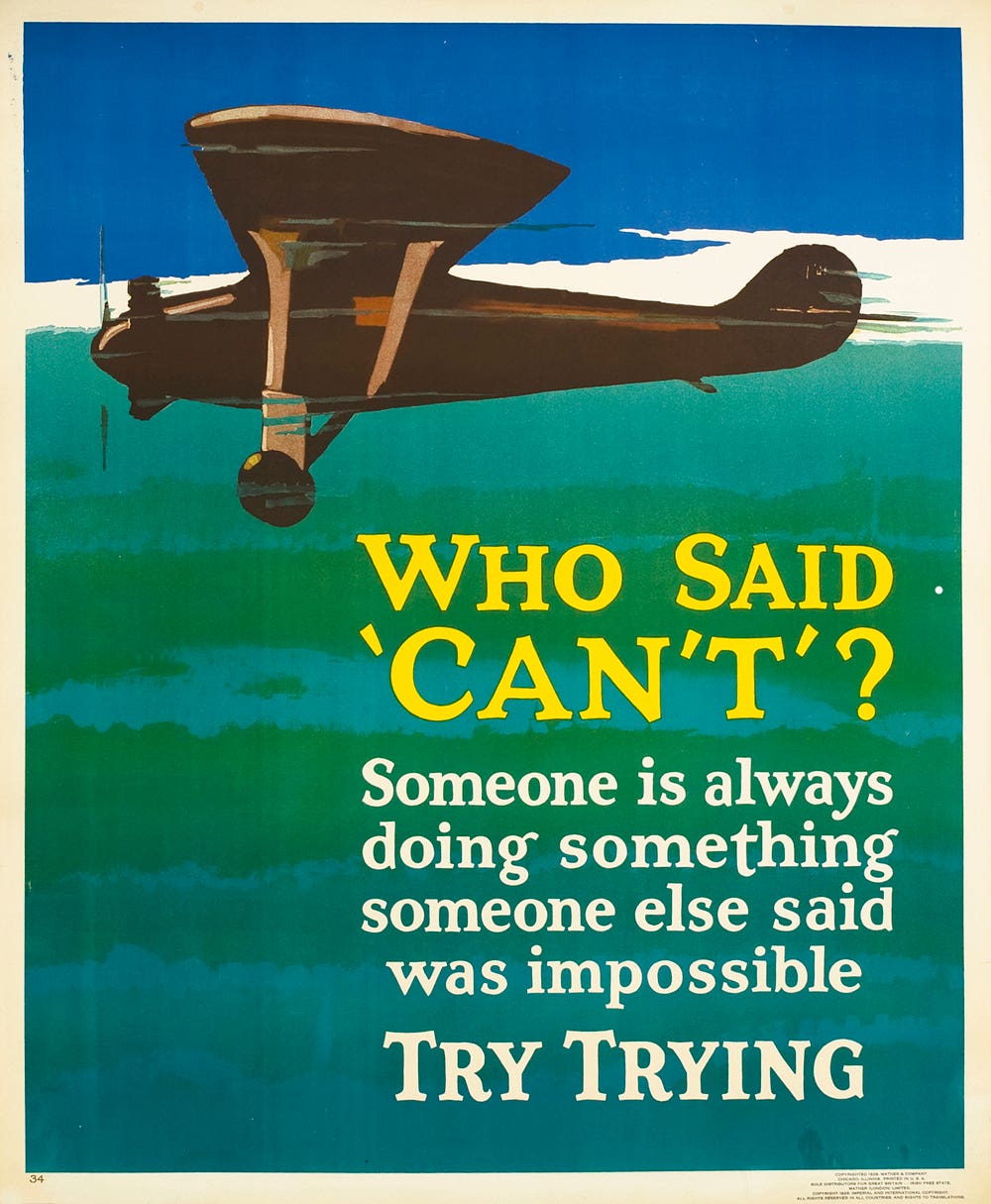

1918

Santa appears in classic form on a U.S. World War 1 propaganda poster.

1920s

Rockwell did many Santa-themed covers for the Saturday Evening Post. Like Haddon Sundblom’s depictions for Coca Cola more than a decade later, Rockwell’s illustrations give a physiologically human and naturalistic aspect to the character, as opposed to the more cartoonish features which had gone before.

1942

On a U.S. World War II propaganda poster, Santa takes a radical departure from the jolly red suit and dons the dour shades of war.