Solving Provenance Mystery

The history of a piece is critical in understanding its personal story and value. Here’s how you can be the detective of your own collection.

The word provenance is derived from the French term provenir, meaning “to come from.” When a collector considers purchasing a work of art, the subject of the work’s provenance is often brought up. When the term is used in fine art, or antiques, it refers to the history of the ownership of a particular piece—the piece’s personal story.

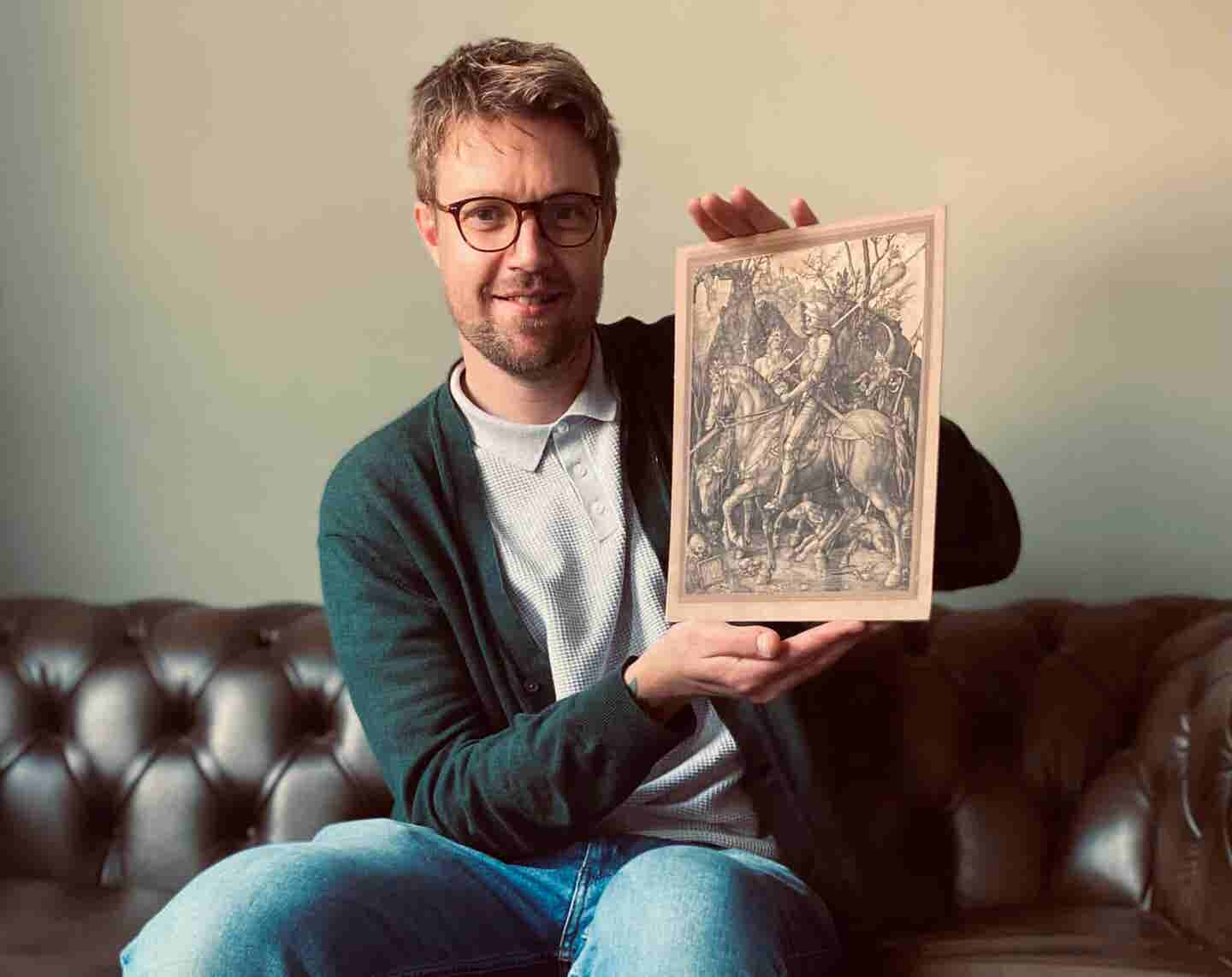

Reviewing, vetting and tracking the history of an object can be a profession all on its own. Uncovering an inscription, discovering a piece in the background of a photo, or looking at the condition of a piece can all weave an interesting narrative about a piece.

The most fundamental forms of provenance are original documents that can trace the ownership of the piece back to the artist. However, frequently as pieces have passed hands over the generations—many times before the Internet and electronic records were available—some of these documents may have been damaged or lost. While there may not be a complete set of pedigree established when reviewing a work for sale, generally the most accepted forms are:

Certificate of authenticity: Issued and signed by the artist or a recognized expert on the artist.

Receipt or Invoice: The document should identify the item as well as the buyer and seller. These documents can help with a work’s timeline and the proof of ownership.

Gallery and Exhibition Labels: These labels identify the title, size, artist and if applicable, the date or show where it was exhibited. This information can often be corroborated online

Auction Documents and Labels: Auction labels are coded with the date of sale, lot number and auction house. These details can usually be straight forward to cross reference the work online for sale results as well as old auction catalogs.

Catalogue Raisonné: Is a comprehensive listing of the accepted artworks of a particular artist that has been created to assist third parties in validating works by the artist and to protect the market from forgeries. The absence of a work in an artist’s catalogue raisonné should not be taken lightly.

Accession Number: Items from museums and corporate collections are assigned a number for identification within their collections. The number is usually inscribed directly on the back or underside of a piece. If a piece is deaccessioned, that assigned number stays with the piece as part of its provenance. Through research you can cross-reference and verify the piece within that collection.

It should be noted that some of the best forgers have made a career out of forging not only the artwork, but also the provenance for their pieces. The documentation that is presented with a piece should be original and should be verified before purchasing an item.

When vetting a piece, there are other physical clues that can help uncover a work’s past and support its provenance. Many collectors enjoy the sleuthing and research that is involved tracking the history. Some of these clues can tell the story of how the piece has been cared for, repaired, altered, or even the environment that it has been in.

Frame Labels: Labels from frame shops can help date a piece and help with a geographic location. I have fielded several calls over the years from collectors who have purchased a piece and have come across a label and called to see if anything can be deciphered from the information on the label.

Artist Material Labels: Take a look at the back of the piece. Are there any supplier labels or stamps on the artist materials? You can investigate artist material logos online to help determine the age of a piece.

Stretcher bars: The wood frame that a canvas is attached to can vary from the way it is joined to the wood it is constructed with. If a painting has been previously restored, the original stretcher may have been replaced with a new stretcher.

Tacks versus Staples: Staples started to be used to secure canvases to their wood stretchers in the 1940s. Look for the presence of old tack holes if staples are present on an older painting.

Old versus New Frame: Has the painting been reframed? Look at the back of the frame to see if it might be in the original frame. Does the back of the frame appear aged with wear? Is there old hardware that would place the piece in the wrong orientation?

Nail Holes: How is the painting installed into the frame? Do all of the nails and nail holes line up with the holes in the stretcher and the frame?

Dusting Damage: Look at the front of the frame. The top and the lower edge of the frame often have the most wear through the finish. This is from years of cleaning dust along those horizontal surfaces, resulting in gradual damage to those areas. If the piece has a new frame, you can still look at the condition of the stretcher to see if it has evidence of old nail holes and mounting hardware from previous frames.

Condition: With older paintings, it is rare that you come across a piece that is in mint condition. Having a conservator look at a piece can yield much insight into the piece’s current condition and also its past. As a painting ages, its protective varnish can darken and discolor. Environmental grime and dust can collect on the surface and darken the paintings appearance. Depending on the exposure, different cracks or a network of craquelure can occur throughout a painting, some more concerning than others.

Previous Conservation: It is not uncommon to come across paintings that have been previously restored or conserved. Often a conservator will adhere a label describing the treatment to the back of a piece after it is treated. If a label is not present on the back, look at the tacking edge to see if the painting was lined, the type of stretcher that was used, or signs of mismatched overpaint on the surface as possibly evidence of prior work.

Moisture Damage: Rusty staples, tacks or a warped stretcher can signify that a work was stored in a damp or humid environment.

Soot: A piece that has a light layer of soot might not necessarily signify it was in a fire but could be evidence that it was installed over a fireplace for years when it was in previous hands. While it is traditional to hang a prized painting over the fireplace mantel, it is often one of the worst places for a cherished piece, given the prolonged exposure to soot and variance in temperature.

Nicotine: Second-hand smoke can cause the build of nicotine on the surface of your artwork and antiques. It creates a warm brown tone over the surface which obscures the color and detail in paintings. Its presence also yields evidence that the piece was in the home of a smoker. A client once brought in a high-profile painting that had recently been acquired at an auction of an esteemed collector. We noted the presence of the heavy layer of nicotine, and the client, said, yes, well, this is further proof that this painting was on display in his home, because he was known as an avid smoker! Regardless of the story behind the presence of the nicotine for that piece, it was decided to have it cleaned to preserve the painting as well as reveal the proper tonality of the paint layer.

It is always important to verify the provenance that is presented to you. A credible seller should always provide the documents prior to a transaction. Remember that appreciating the work of art, verifying the documentation and reviewing its historic condition can all be helpful when researching a piece. Even if you decide to not proceed with a purchase of one piece, you might just discover another artist, work, or story that is even more interesting to pursue.

April Hann Lanford is the Principal of Artifact, a Chicago firm specializing in the preservation and protection of works of art and historical artifacts. April works with clients nationwide and has wide-ranging experience in the recovery of fine art and antique collections in large-scale disasters. She can be contacted at april@artifactservices.com.