The Charming World of Beatrix Potter

The Tale of Peter Rabbit and other stories by the celebrated English author and illustrator are still popular today.

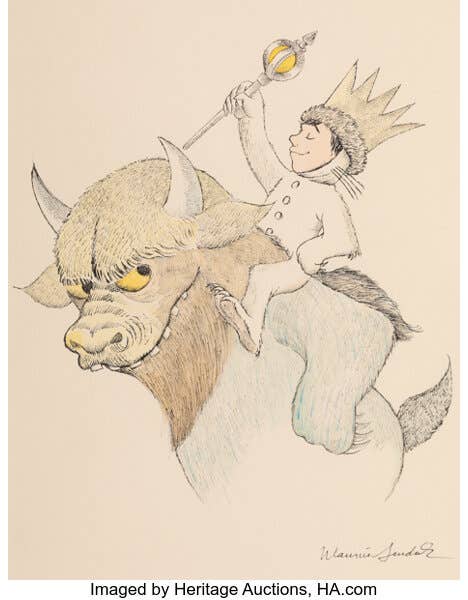

In one of Beatrix Potter’s watercolors for The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Peter huddles against a door in a wall in Mr. McGregor’s garden. With delicate strokes, Potter paints one of Peter’s small feet covering the other. She positions the feet just as a rabbit would in that situation. A little tear rolls down his cheek, as he asks an old mouse the way to the gate. He has eaten some of the farmer’s vegetables and now must escape to the woodland. However, the mouse has such a big piece of pea in her mouth, she cannot speak and help him.

It is these wonderfully exact details that make Peter Rabbit one of the most well-known and loved stories, and Potter one of the best-selling and best-loved children’s authors in the world. It is also one of the reasons the figurines, sketches, and books of the characters are collectible.

Peter is also featured in a new movie now playing in theaters, Peter Rabbit 2: The Runaway, which — no surprise — features plenty of mischievous adventures. The first movie, Peter Rabbit, released in 2018, grossed $115.3 million in the United States and Canada, and $235.9 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $351.2 million.

Potter will also be featured in a major exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2022.

Potter wrote and illustrated 28 books, including her 23 Tales, that bring to life many beloved animal characters, including Peter Rabbit, Benjamin Bunny, Mr. Jeremy Fisher, Jemima Puddle-Duck, Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, and others. Her enduring stories remain popular and have sold more than 100 million copies. The Tale of Peter Rabbit alone has been translated into more than 45 languages. In her later years, she was a farmer and sheep breeder in the Lake District.

Potter has instructed young readers in her early 19th century British morals for years in her gentle, whimsical tales and watercolors. Squirrel Nutkin and Mr. Jeremy Fisher would be so proud.

Helen Beatrix Potter was born on July 28, 1866, to Rupert and Helen Potter in Kensington, London. She had one younger brother, Walter Bertram. She never went to school, but she did have several governesses and an art teacher, Miss Cameron, and loved to draw at an early age. In British author Matthew Dennison’s 2017 book, Over the Hills and Far Away: The Life of Beatrix Potter, he said, “Art was a compulsion for Beatrix.”

Beatrix Potter Was Inspired By Animals

Cameron encouraged her to draw intricate sketches, and her renderings of the little animals and insects in her books were so precise because from a young age, her parents wanted her to observe wildlife. They filled her holidays with visits to the countryside, first to Scotland and then in 1882 to the Lake District of England, where she made her home as an adult — first at Hill Top Farm in 1905 and Castle Farm in 1909. To appreciate Potter’s great artistry and humor, visit The Tale of Benjamin Bunny for her illustration of the too-big blue tam-o’-shanter on Benjamin’s head.

Many of Potter’s pets served as models for her characters. Jeremy Fisher was drawn partly from Punch, her frog. Her rabbit, Peter Piper, who accompanied Potter everywhere, became Peter Rabbit. Benjamin Bouncer was Benjamin Bunny.

Dennison said, “Teaching her hedgehog to drink milk from a cup, she had imbued nature with human personality.”

Beatrix Potter Started as a Naturalist

As an adult, she became obsessed with drawing and finding fungi, studying more than 300 kinds. The website, peterrabbit.com, says, “Encouraged by Charles McIntosh, a revered Scottish naturalist, to make her fungi drawings more technically accurate, Beatrix not only produced beautiful watercolors but also became an adept scientific illustrator.” The skill in her detailed rendering of the wildlife in her books is proof.

On April 1, 1897, George Massee read Potter’s paper, “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricinae,” to the Linnean Society of London. They determined it needed more work before its printing, but probably because she was a woman, her work was not taken that seriously.

Caitlin Goodman, curator of the Rare Book Department at Free Library of Philadelphia, said that after Potter hit barriers in the scientific world, she went into children’s books, producing one or two a year.

It was not a hard step for her imagination to make. Even before she began writing Peter Rabbit, Dennison said that in Potter’s journal, she wrote that she could see all her little fungus people singing, bobbing, and dancing in the grass.

Before Peter Rabbit, Potter wrote a book of poetry titled, A Happy Pair, that came with greeting cards. The Free Library has the original first edition from 1890.

Peter Rabbit Was Not an Immediate Success

Potter also gave story letters, with the illustrations separate, with animals as the characters to the children of her last governess, Annie Carter Moore. Moore’s eldest son, Noel, was a sickly child and Potter wrote a story for him called, The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Mr. McGregor’s Garden. Moore encouraged Potter to take it to publishers, but it was rejected.

Potter was undeterred. An astute businesswoman who became the impetus behind her books and merchandise, she commissioned Strangeways & Sons of Tower Street, London, to print booklets; they were 5 inches by 3-1/4 inches and illustrated in black and white. The Art Reproduction Company of Fetter Lane engraved the illustrations, and Hentschel of Fleet Street produced the colored frontispiece. Potter ordered 250 copies from Strangeways and 500 frontispieces in case of a reprint.

On December 16, 1901, the story, renamed to The Tale of Peter Rabbit, was privately printed. Potter sold all of them, including the 200 reprints.

The Warne Company heard about its success and convinced Potter to make a shortened version of the book done in watercolors, which was published in 1902. The Tale of Peter Rabbit remains her most popular book in the world.

In 1903, Warne produced The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin and The Tailor of Gloucester. Warne and Potter worked together on the rest of her 23 books until her eyesight and stress from her farm work stopped her from producing more.

“One of the many one-of-a kind objects we have is the Tailor of Gloucester manuscript, handwritten by Beatrice Potter,” Goodman said. It was actually a 1901 Christmas gift for Freda Moore, Noel’s sister (composition book and the illustrations). She painted the watercolors separately. It was later published commercially by Warne in 1903 in a much-shorter length. Potter re-drew all the illustrations.

The Free Library of Philadelphia has more than 100 pieces of original artwork by Potter.

“We also have dozens of letters by Potter. Then there are all of the first editions of all of her works, including ones that were privately printed,” Goodman said. The library has two of the first 250. Goodman said that includes “one that Potter presented to her cousin, Stephanie, in 1901, which is just one of the many autographed copies in the collection.”

Beatrix Potter Understood Merchandising

Potter licensed her creations. She designed and created her Peter Rabbit doll in 1903, registering it at the patent office. According to peterrabbit.com, it is the world’s oldest licensed literary character. The Free Library has ones from 1913. It also has a Peter Rabbit fold-out 1930ish Race Game with pieces and box that Mary Warne designed after the more complex version Potter did for two players in 1904.

In 1913, Potter licensed a Peter Rabbit Jemima Puddle-Duck painting books. Children have already painted many of the illustrations. Goodman finds a painting book untouched less interesting because, “I like thinking about the life the book had before it came.” She feels the value of the object is less important than the tale behind the item with all the collectibles in the library’s collection.

According to peterrabbit.com, Potter “felt passionately that all merchandise should remain faithful to her original book illustration and be of the highest quality.”

Two of the library’s collectibles recently donated that are Goodman’s favorites include some 1910 little papier-mâché figurines of the characters that were never for sale and only used by the booksellers at their stands for marketing purposes. They are handmade and smaller than the Doulton figurines. Goodman also gets a kick out of a 1942 tacky magic book with accessories.

The library’s rare book department plans to provide some access to exhibits in July and will later further reopen to in-person tours and programs.

You can learn about the values of Potter’s figurines in the book, Storybook Figurines: Royal Doulton Royal Albert Beswick (A Charlton Standard Catalogue; 8th edition) by Jean Dale, and Beswick Collectibles, 10th edition, both produced by Charlton Press in Quebec, Canada. Every couple of years, a new edition comes out with changing auction prices.

On February 12, 2022, tentatively, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London will open a major exhibit of Beatrice Potter titled, “Nature’s Visionary,” for fans’ enjoyment. It will run through September 25, 2022. The V&A is a major resource for the study of Potter. The museum holds the world’s largest collection of her drawings, manuscripts, correspondence, photographs and related materials. Besides studies for her Tales, nursery rhymes and fairy tales, the collection is strong in natural history and landscape watercolors and includes some family archival material.

After the visit, you will never forget the true masterfulness of Potter’s works.