Rockwell Kent: A Force of Nature

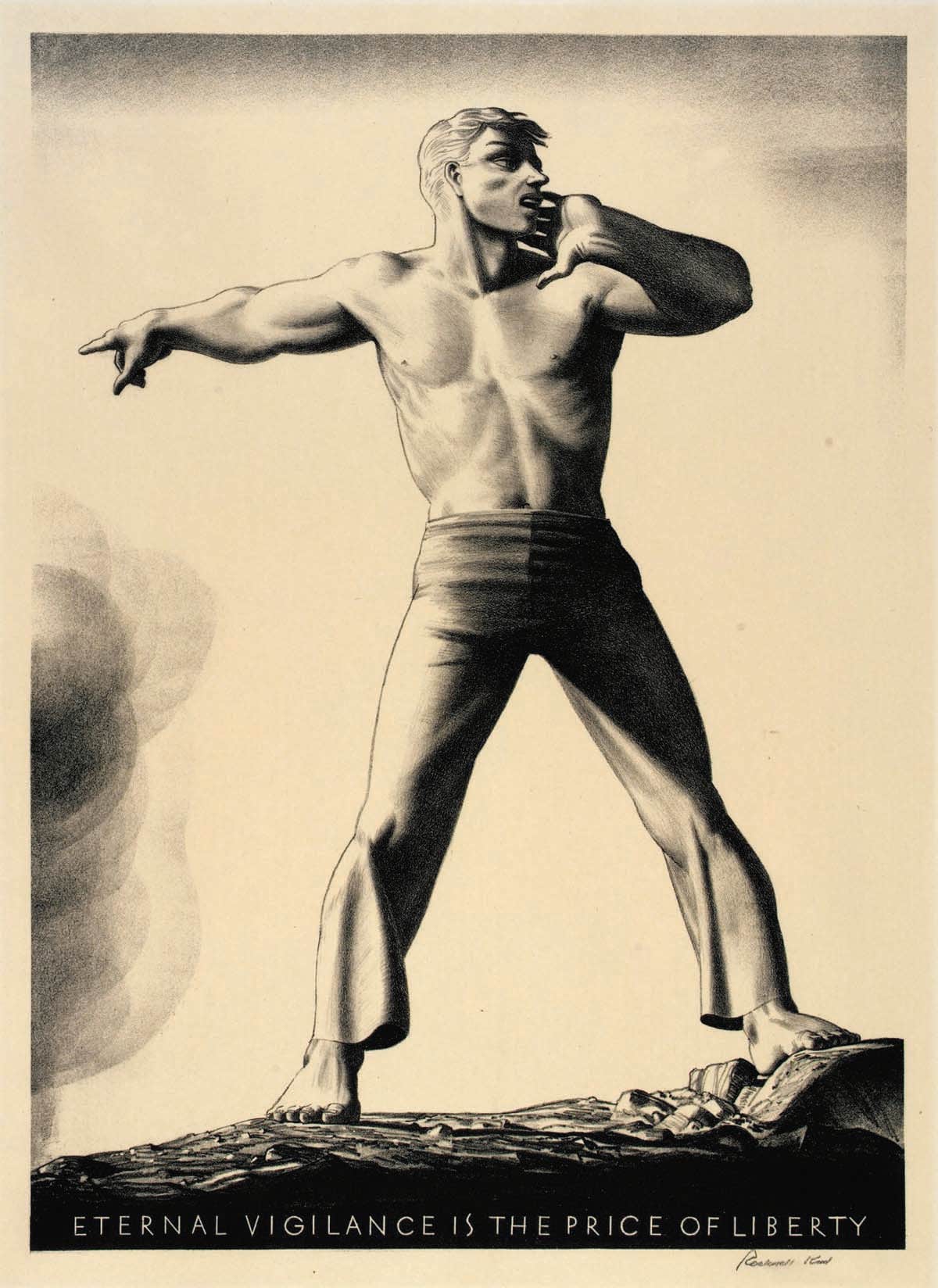

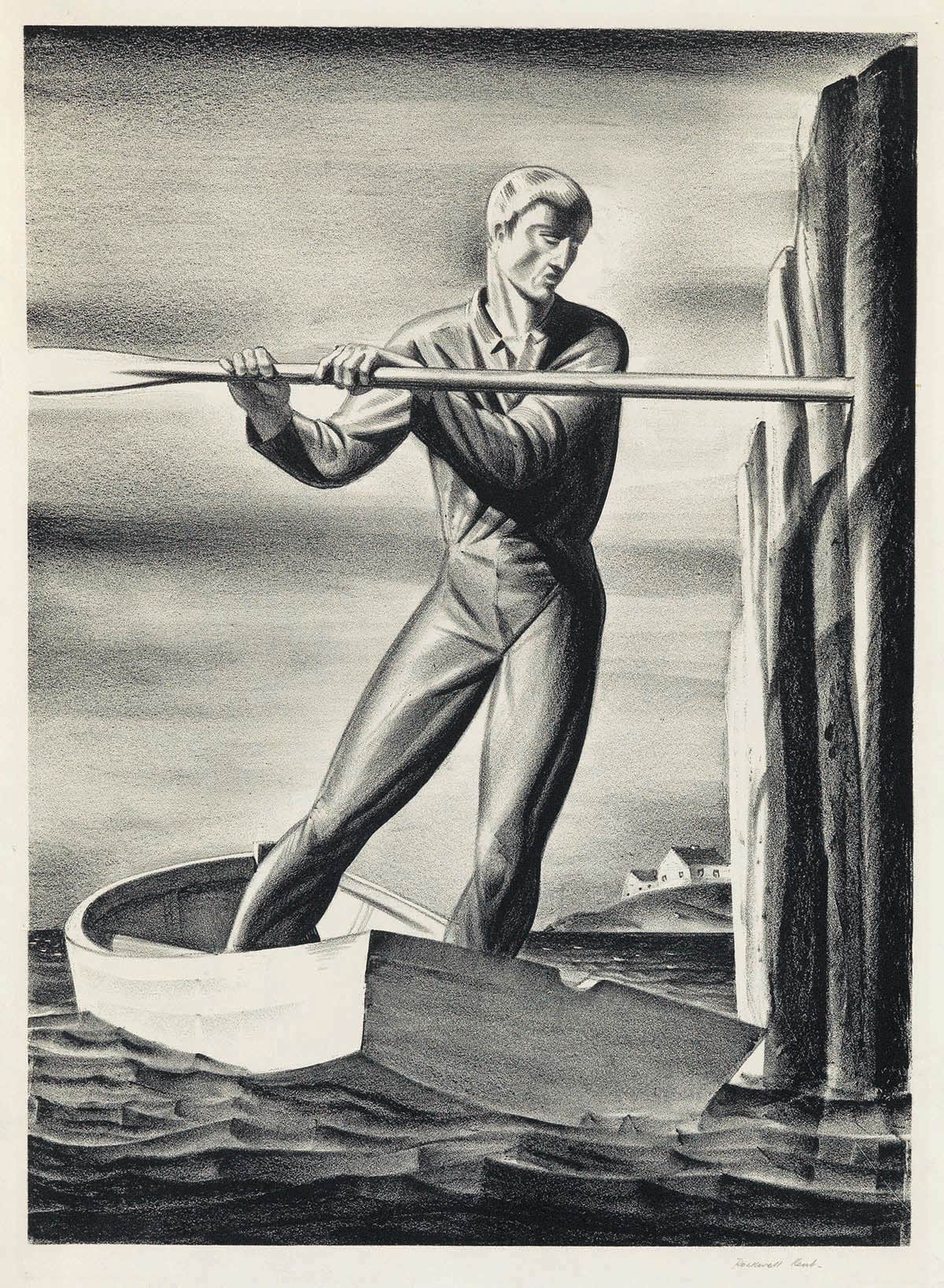

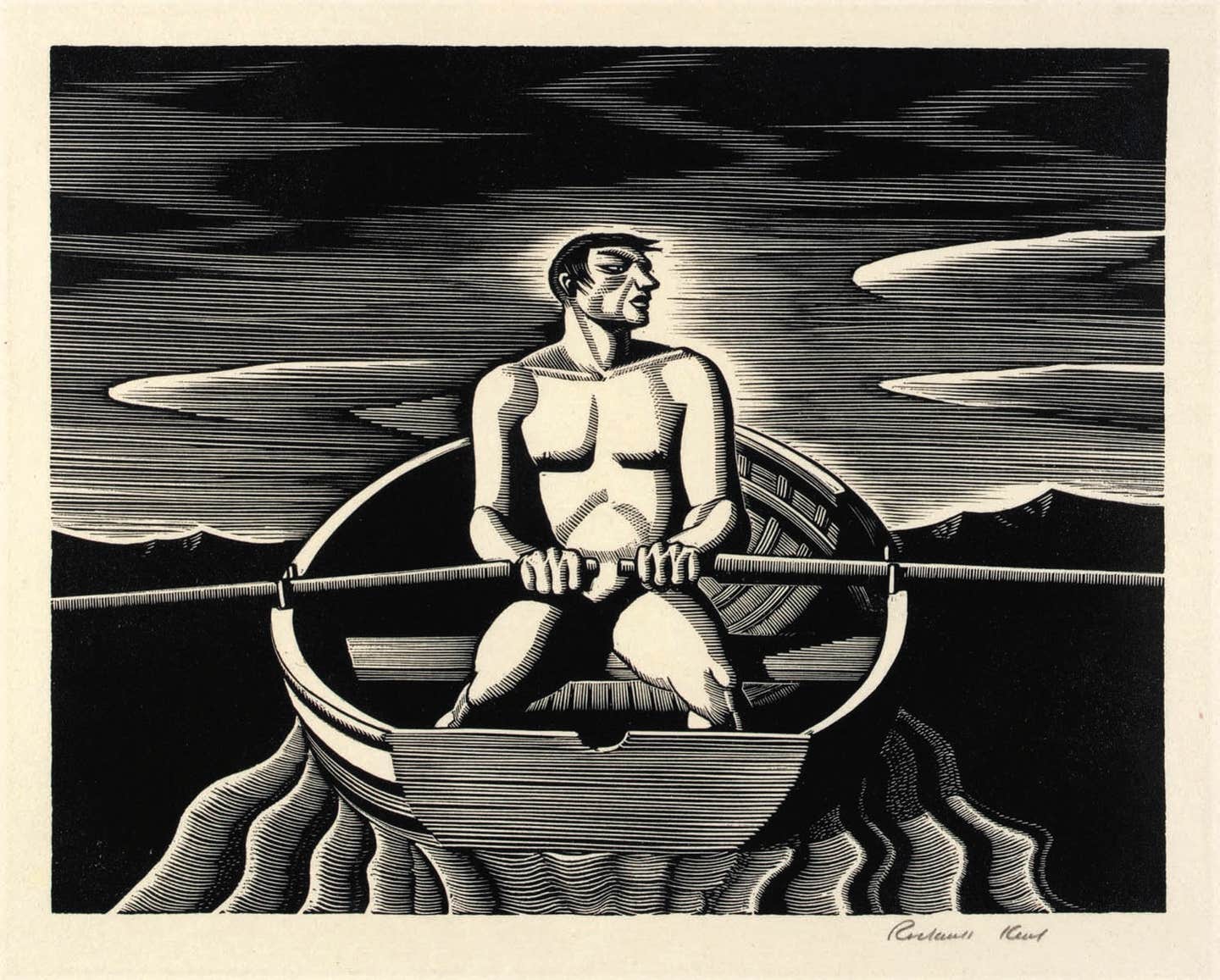

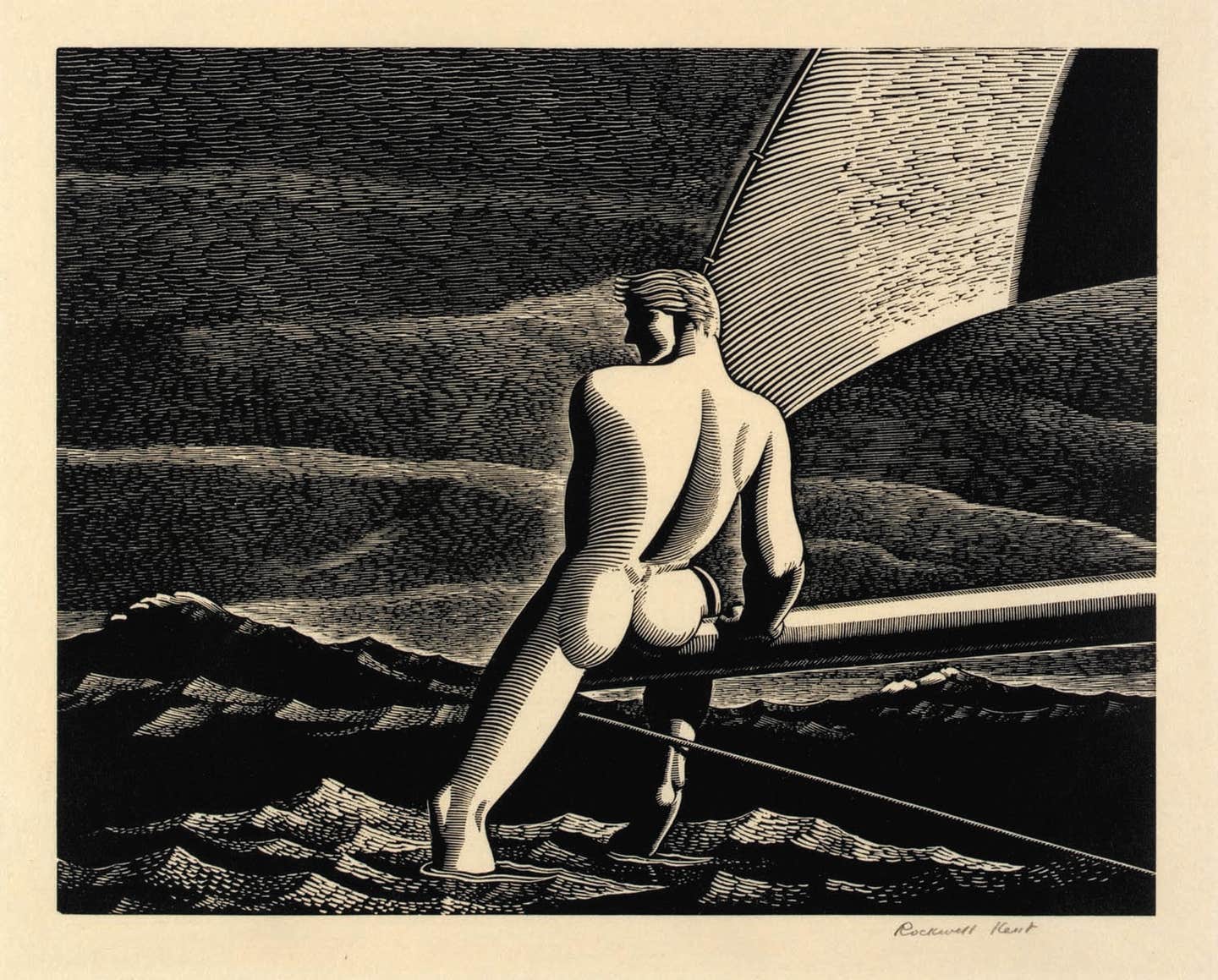

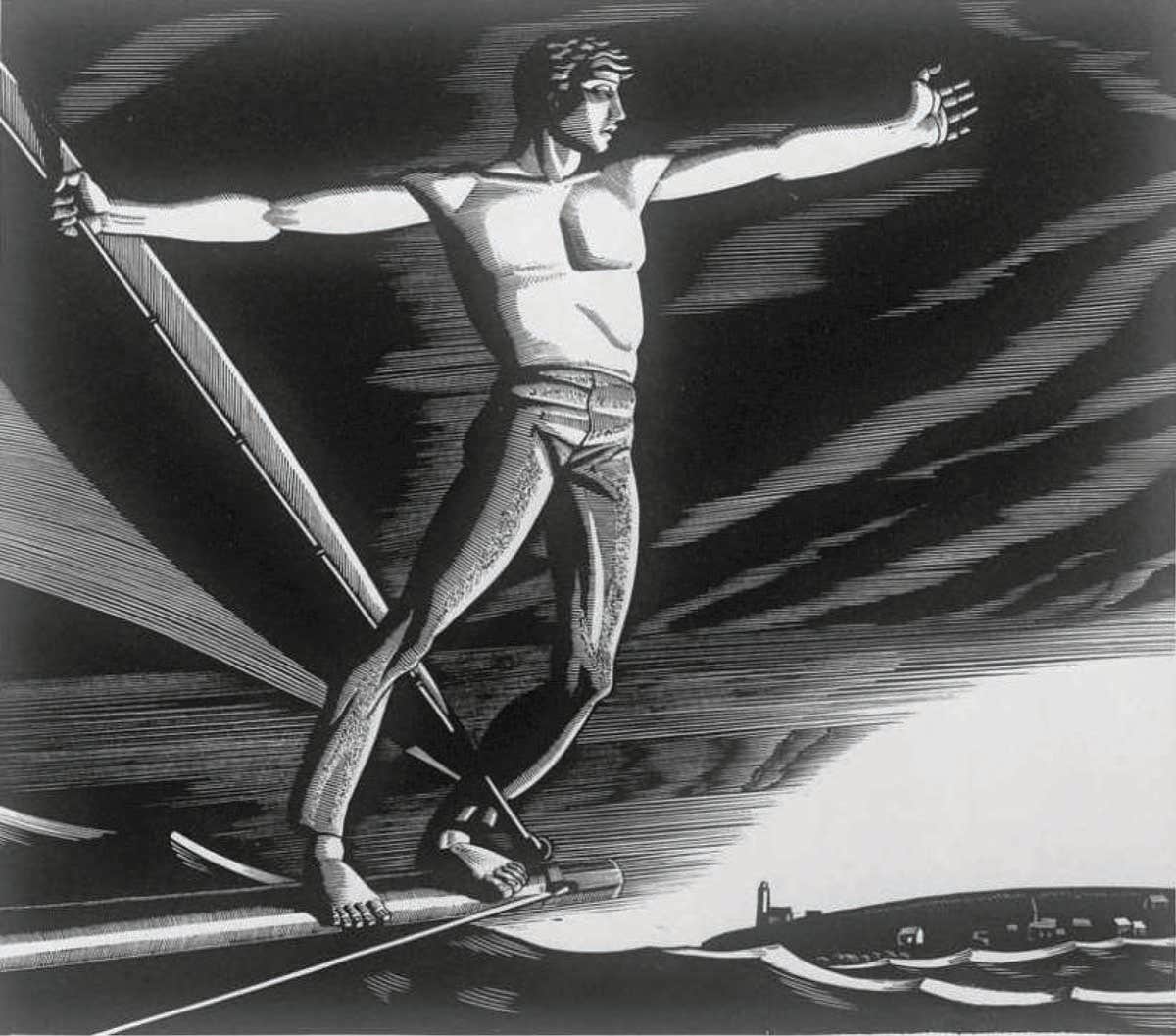

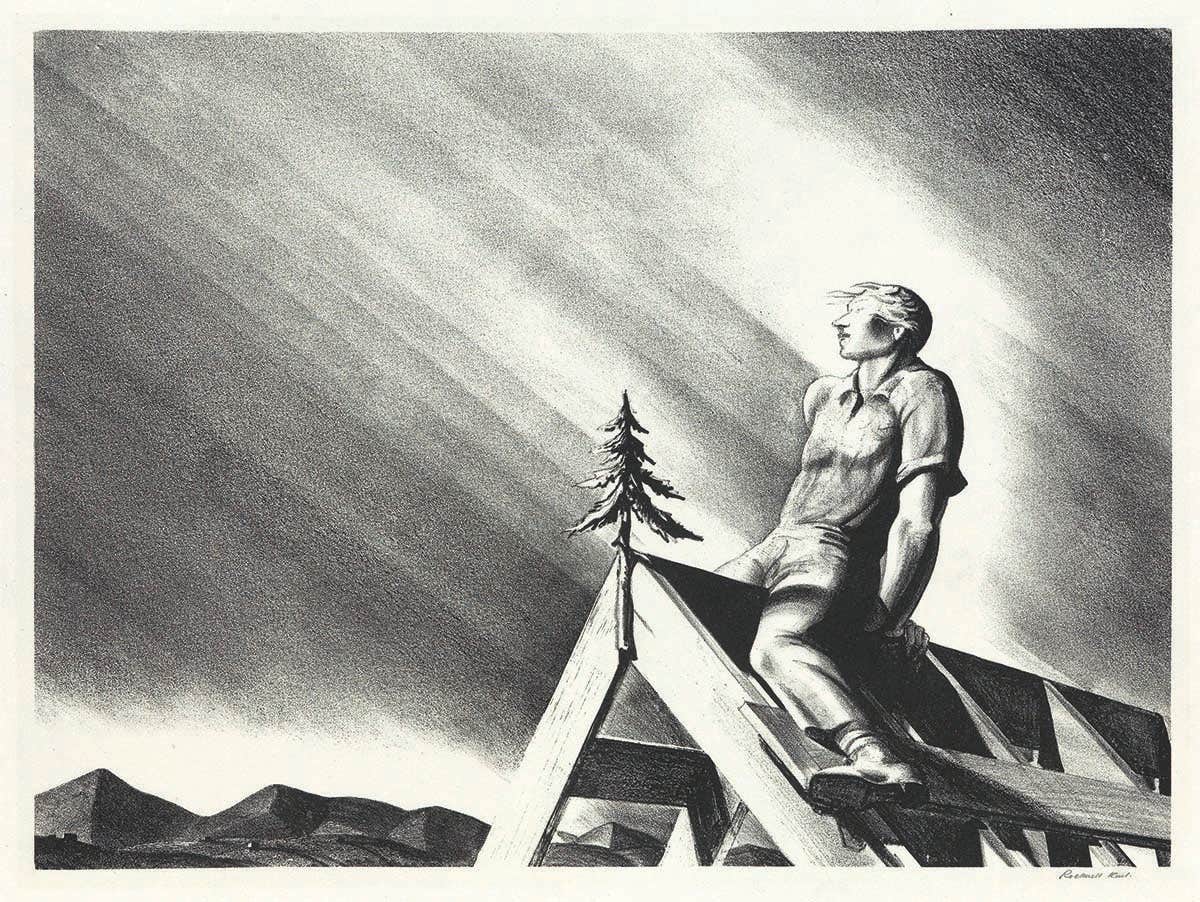

The artist’s world was of an uncompromising Nature—frozen wastelands, steep rocky cliff, and violent tides—drawn from his own extensive travels. Kent’s figures were heroic, almost mythic characters who exhibited grace yet loneliness.

Rockwell Kent flexed rugged. It’s simplistic to call him a “man’s man” but if you were to argue the point you probably would win the debate. Kent (1882-1971) was an architect, lobsterman, dairy farmer, carpenter, explorer, something of a musician, author and, of course, an artist.

The man’s talents practically dripped testosterone. He looked the part as well.

Kent’s obituary in The New York Times described him as “lean and sinewy” with a “long, square-jawed face . . . dominated by burning gray eyes under bushy brows.” He possessed a fiery personality to boot. What’s more, Kent was stubborn, with an ironclad will. Although he stood only 5’ 9”, he was formidable.

So it’s no surprise that his work as an artist was strong and powerful, speaking of a demanding world and the men (mostly) who summoned the strength to survive in it.

Kent is best known for his wood engraving started in the 1920s. His world was of an uncompromising Nature—frozen wastelands, steep rocky cliff, and violent tides—drawn from his own extensive travels. Kent’s human figures were heroic, almost mythic characters. And yet there is grace and a suggestion of loneliness.

His work reflected his extended stays in Maine, Newfoundland, Alaska, Tierra del Fuego, and Greenland. As art historian Alan Wallach has observed, “Life in such forbidding settings sustained and intensified his original vision of a relentless, unforgiving nature.”

He quickly established himself as one of the preeminent graphic artists of his time. His striking illustrations for two editions of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick were extremely popular and remain some of his best-known works. All told, Kent illustrated 37 volumes during a career that extended more than 55 years. Besides, Moby Dick and his own book on travel and adventure, his work illustrated such classics as Casanova’s Memoirs Voltaire’s Candide, Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, Goethe’s Faust, Beowulf, Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis and an edition of his complete plays.

His powerful and innovative book graphics, which included everything from full-page lithographs and wood engravings to borders, capitals and bookplates, have influenced generations of graphic artists.

While Kent’s paintings, etchings and woodcuts reflect an adventurous spirit, his travels to distant shores also developed his sympathy for working people. “I am still disturbed by the fact that there are some people with a lot of money,” Kent once said, “and a lot of people with no money and a few million with no jobs.”

Kent’s feelings toward the hardships of the working class didn’t go unnoticed. He was caught up in the Cold War of the 1950s, questioned by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his Red Scare cronies for his social and political beliefs. Although he never joined the Communist Party, his support of Leftist causes made him an easy target of the State Department, which revoked his passport after his first visit to Moscow in 1950 (though Kent successfully sued to have it reinstated).

Infuriated at American galleries and institutions that shunned his art because of the political controversies and changing attitudes, Kent gave an enormous collection of his work – 80 paintings and 800 prints and drawings – to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. His gift made him a hero in Russia.

Today, Kent’s work is highly collectible and does well at auction. A favorite with the art crowd are his paintings of mountainous Arctic landscapes, which emerged after he visited Greenland three times between 1929 and 1935. He painted Gray Day during his final trip. Gray Day sold for more than $800,000 in 2016, a record for Kent’s work.

In his 1955 autobiography, It’s Me O Lord, Kent shared thoughts on his beliefs that defined his art: “God had become to me the symbol of the life force of our world and universe; a name for the immense unknown. Imponderable, yet immanent in man, in beasts… in the earth, sun, moon and stars”

Paul Kennedy is Editorial Director of the Collectibles Group at AIM Media. He enjoys Mid-century design, photography, vintage movie posters and people with a good story to share. Kennedy has more than twenty-five years of experience in the antiques and collectibles field, including book publishing. Reach him at PKennedy@aimmedia.com.