It was May 22, 1980, and American kids – as well as their poor, bewildered parents – had no clue what was about to hit them.

Pac-Man, the revolutionary video game released by the Japanese company Namco, emerged from the Far East like a modern-day Godzilla, laying waste to anything and everything in the video game landscape.

With its colorful design, likeable character and simple eat-the-dots maze gameplay, Pac-Man was instantly addictive. What’s more, the cute and cartoonish game was attractive to women and teenage girls, a breakthrough in the burgeoning video game world dominated by testosterone.

By one count, Namco sold 400,000 Pac-Man machines, head and shoulders above anything that had come before, or since.

But Pac-Man was more than a hit video game. It was a happening. Everywhere you looked, there was Pac-Man: On cereal boxes, T-shirts, pajamas, lunch boxes, television, even on radio as a hit song, “Pac-Man Fever.” The lovable scamp was gaming’s first true franchise.

To celebrate Pac-Man’s 40th birthday, we sat down with noted toy expert Mark Bellomo, author of Totally Tubular ‘80s Toys, and a Pac-Man playing fool back in the day, to discuss the game’s popularity and to relive the glorious days when video arcades were boss.

Antique Trader: You were a child of the ’80s. Did you contract Pac-Man Fever?

Mark Bellomo: As a child of the 1980s, catching such a virulent illness such as Pac-Man fever was absolutely unavoidable for an introverted, bespectacled, 98-lb. (soaking wet), Dungeons & Dragons-playing, action figure collecting, comic book-reading, dyed-in-the-wool nerd.

I embraced video gaming and the video subculture that developed in its wake because in order to play video games, you didn’t have to be big and athletic in order to succeed: all that video gaming required was good hand-to-eye coordination, decent reflexes, and … a stout imagination. Since I’ve always been a hard worker —usually juggling three or four jobs at a time — I always seemed to have a bit of extra money at hand in order to play video games as they were meant to be experienced: in a video arcade — which was a pretty expensive hobby.

You see, while most modern gamers believe that playing the arcade cabinet-based games back in the early 1980s was relatively inexpensive, between January 1, 1981 and April 1, 1990, the minimum wage in New York State was a mere… $3.35 per hour.

What does this mean? That playing one video game, once — at 25¢ per try — cost approximately 7-8% of my hourly wage. Back in the early eighties, $1 was nearly one third of what I made per hour. So then, if I dropped (only) a fiver on video games each week, I spent well more than an hour’s worth of pay. Blowing $10 on video games? Well, that meant squandering an entire afternoon’s worth of gainful employment.

So why do it? It wasn’t JUST for the thrill of playing the game. There was a cherry on top of the sundae that is Pac-Man.

What many folks forget about the arcade culture of the early 1980s was that there were external rewards for succeeding in public gameplay. For instance, if you obtained the high score for a game at my local arcade (the “Time · Out” arcade franchise located in the Auburn, New York Fingerlakes Mall), they’d write your name onto a list that was placed atop the arcade cabinet in question, AND you’d receive four 25-cent tokens for further gameplay.

The games in which I regularly garnered the high score (and was gifted my free tokens) were Midway’s Ms. Pac-Man (1982), R-Type (Nintendo, 1987), and Sega’s Gain Ground (ca. 1988).

Antique Trader: We live in a world dominated by home systems such as Sony PlayStation, Microsoft Xbox and Nintendo Switch, for the uninitiated can you describe the video arcade scene in the 1980s?

Bellomo: The video arcade scene of the early 1980s was darned similar in scope and method to the modern casinos of Las Vegas and Atlantic City: ostentatiously colorful architecture, vibrant lights strobing and flashing, bells and electronic sounds ringing and tweeting, and the lack of any semblance of the passage of time — all which were designed to separate kids from every single quarter lining their pockets.

Before the rise of (second generation) home entertainment/video game systems such as the Atari 2600, Intellivision, Odyssey, and Colecovision, and then during the systems’ proliferation and eventual glut on retail shelves (and downfall of the systems) in ’82, the video arcade environment thrived. The reason: The graphics and gameplay of arcade video games such as Pac-Man, Asteroids, Galaga, Frogger and Donkey Kong were far superior to those same games when translated onto a cartridge for home-based console game play.

There was simply no competition between Pac-Man the arcade game (whether cabinet or tabletop version) and Pac-Man the console game offered by Atari, Intellivision, and the like: Every single aspect of the arcade gaming experience was superior to the relative comfort provided to a gamer when playing the “same title” at home.

Antique Trader: Space-shooter games such as Asteroids and Space Invaders dominated video games arcades. But Pac-Man, a simple chase game, changed all that. What was the attraction?

Bellomo: Basic. Direct. Imaginatively simple.

That was Pac-Man.

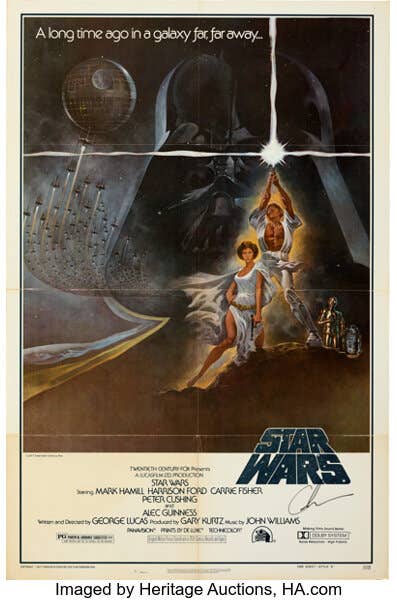

No complex backstory. It was a very appealing game that made accessible by design. In a male-dominated industry like that of video games — particularly in Japan — the Namco company’s designers were given an edict: attract more female players into male-dominated arcades, and Pac-Man was intended to do just that. It offered more than the established conventional, run-of-the-mill space-shooter games that then dominated the industry and which built upon a male-dominated Luke Skywalker/Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers sci-fi adventure fantasy.

The strategy of Pac-Man could be comprehended by anyone at a mere glance: a bright yellow character with a furiously opening mouth is chased by a quartet of fast, colorful ghosts. The yellow character’s job is to eat every single dot within each maze, “clearing the board,” before being caught by a ghost. However, the tables could be turned on the villainous spooks if the yellow character could eat any of the four Power Pellets — large, flashing dots which were strategically placed in each one of the four corners on the map. Once consuming a Power Pellet, the yellow character, “Pac-Man,” was energized and made powerful enough to eat any of the ghosts — albeit for a limited time.

Appearing more similar to the harmless-looking McDonaldland “Fry Guys” in design than any ghoulish spectres that appeared within a Universal Classic Monster movie, the colorful ghost enemies of Pac-Man had personalities all their own — unlike the nameless, faceless antagonists of Galaga or Space Invaders: “Blinky” (aka. Shadow; red colored) was the fastest, most aggressive member of the quartet, Pinky (aka. Speedy; pink colored) was the lone female ghost who used ambush tactics to attack Pac-Man, Inky (aka. Bashful; cyan [greenish-blue] colored) was the fickle member of the four who could either be as aggressive as Blinky or whose tactics could be as ambush-based as Pinky, and finally, there was Clyde (aka. Pokey; orange colored), who acts the fool — targeting Pac-Man in a manner similar to the lightning fast Blinky, then retreating to his home corner when the mood strikes.

The unique properties exhibited by these four spectral adversaries added to fans’ devotion to the game.

But another important (yet simple) aspect of the game also added to its popularity: how Namco’s Pac-Man collated players’ scores: Pac-Man’s running point system is compiled based upon 1) the amount of time it takes you to clear every board by consuming every single one of the tiny dots that have demarcated the numerous passageways within each maze, 2) the amount of ghosts you’ve eaten through the use of Power Pellets — the more ghosts consumed the better; successively ingesting the entire quartet of spooks yields ever more points (!), and 3) the amount and type of randomly appearing bonus items you’ve gobbled which float within the maze as you’re tearing through its corridors. Therefore, scores for the game could easily be compared, and bragging rights for achieving a high score on your local arcade’s revered Pac-Man arcade machine elevated the status of your average geek to that of a daring, swashbuckling adventurer.

Antique Trader: Pac-Man transcended the video-game world. There was Pac-Man merchandise, a carton and even a hit a novelty song called “Pac-Man Fever.” Is it fair to say Pac-Man’s popularity foreshadowed what was to come in regards to the enormity of today’s video games, where its common to see game themes turn into featured films?

Bellomo: Pac-Man surely transcended the video game world, because its chase-through-a-maze simplicity allowed licensees to utilize this simple template to devise a bevy of related product: from successive new arcade games such as Ms. Pac-Man (February, 1982 [Midway]), Pac-Man Plus (March, 1982 [Bally Midway]), Super Pac-Man (October, 1982 [Namco]), Baby Pac-Man (December, 1982 [Bally Midway]), Jr. Pac-Man (August, 1983 [Bally Midway]), and a host of others.

With a broad template, it lent itself to an exceedingly entertaining animated series — one which I never missed every Saturday morning — Pac-Man: The Animated Series (44 episodes; 1982-1983). The cartoon recounted the adventures of the pellet-munching Pac-Man family which contained Pac-Man himself, Pepper Pac-Man (Ms. Pac-Man), Baby Pac-Man, their dog Chomp-Chomp, their cat Sour Puss, as they were constantly pursued by their sworn enemy Mezmaron who enlisted a group of “Ghost Monsters” who were now rendered with full-fledged personalities: Blinky, Inky, Pinky, Clyde, and the all-new ghost, Sue.

From breakfast cereal to T-shirts, TV specials to trading cards, Pac-Man fever took hold of American pop culture for a number of years — and I was most definitely a consumer.

I definitely believe that the merchandising bonanza associated with Pac-Man definitely provided modern video game companies with a successful template for how to develop a successful video game property.

Antique Trader: Would Pac Man be on your Mount Rushmore of Video Games? The other three would be?

Bellomo: If we’re talking about the Mount Rushmore of arcade-based video games, then Pac-Man would MOST DEFINITELY be on my Mount Rushmore of arcade-based games. But I have two versions of arcade-game Mount Rushmore: one that I’ll apply to the world at large, and one that exhibits only my favorite arcade games of all time.

Arcade Game Mount Rushmore — Greatest Arcade Video Games of All-Time:

• Centipede

• Pac-Man

• Street Fighter II

• Super Mario Bros.

Arcade Game Mount Rushmore — Mark Bellomo’s Personal Favorite Arcade Video Games of All-Time:

• Dragon’s Lair

• Galaga

• Gauntlet

• R-Type

Antique Trader: And lastly, you have one quarter in your pocket. Your choice: Pac-Man or Ms. Pac-Man?

Bellomo: Ms. Pac-Man. Simply because I could play Ms. Pac-Man for about fifteen minutes longer than Pac-Man: it was an easier game for me, and I could clear WAAAAAAY more boards.

Paul Kennedy is Editorial Director of the Collectibles Group at AIM Media. He enjoys Mid-century design, photography, vintage movie posters and people with a good story to share. Kennedy has more than twenty-five years of experience in the antiques and collectibles field, including book publishing. Reach him at PKennedy@aimmedia.com.