Waving The Flagg

Illustrator James Montgomery Flagg’s recruiting poster featuring Uncle Sam exhorting “I Want You for U.S. Army” so resonated with the public that it became one of the most enduring images of the 20th century.

James Montgomery Flagg was 39 when the United States entered World War I in 1917, much too old to enlist. Instead, Flagg drew on what he did best, and in the process influenced not only the war effort but also the face of a country.

A leading illustrator of the time, Flagg’s dramatic creation of Uncle Sam exhorting “I Want You for U.S. Army” so resonated with the public that it became a recruitment marvel and one of the most enduring images of the 20th century.

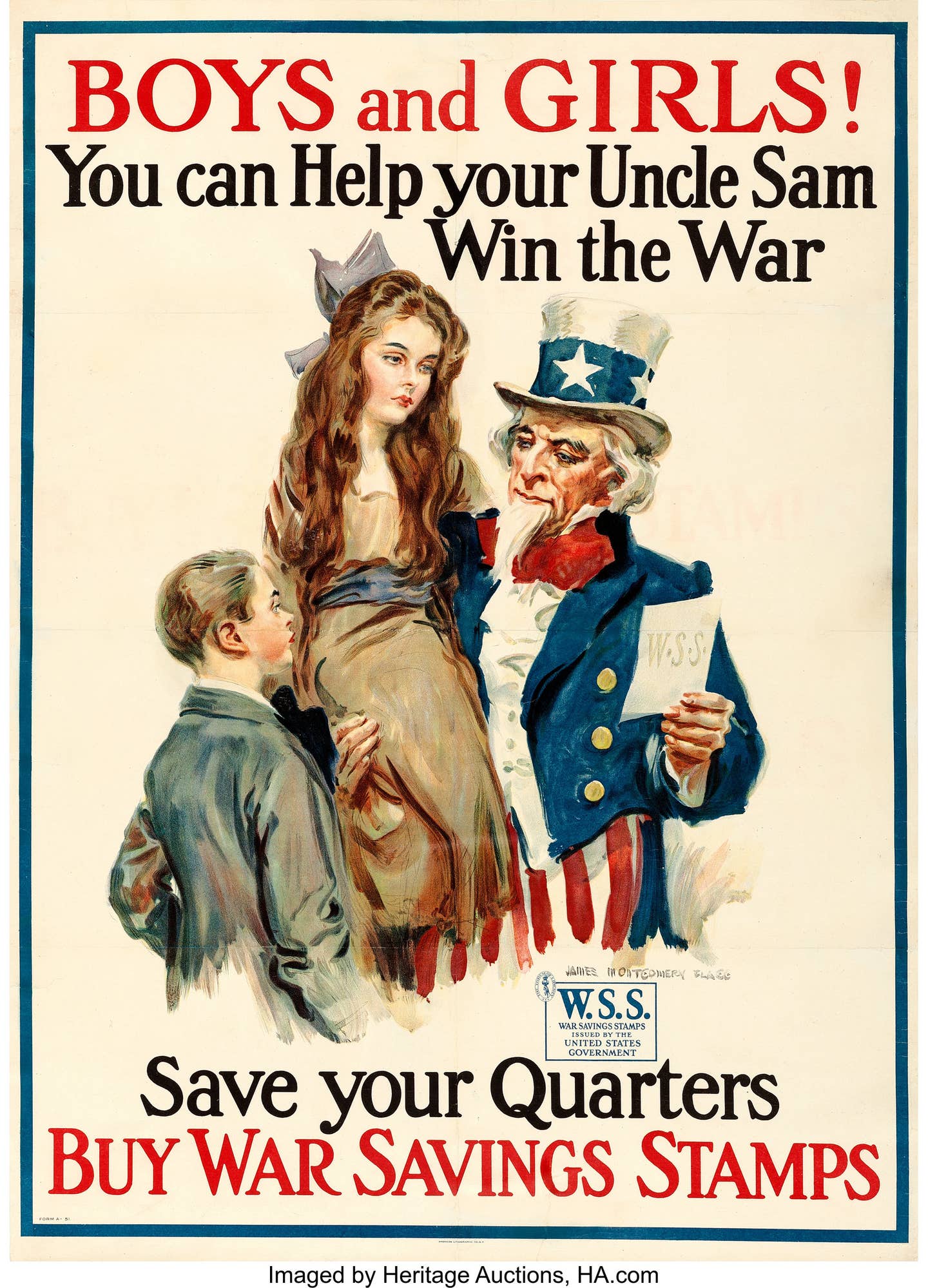

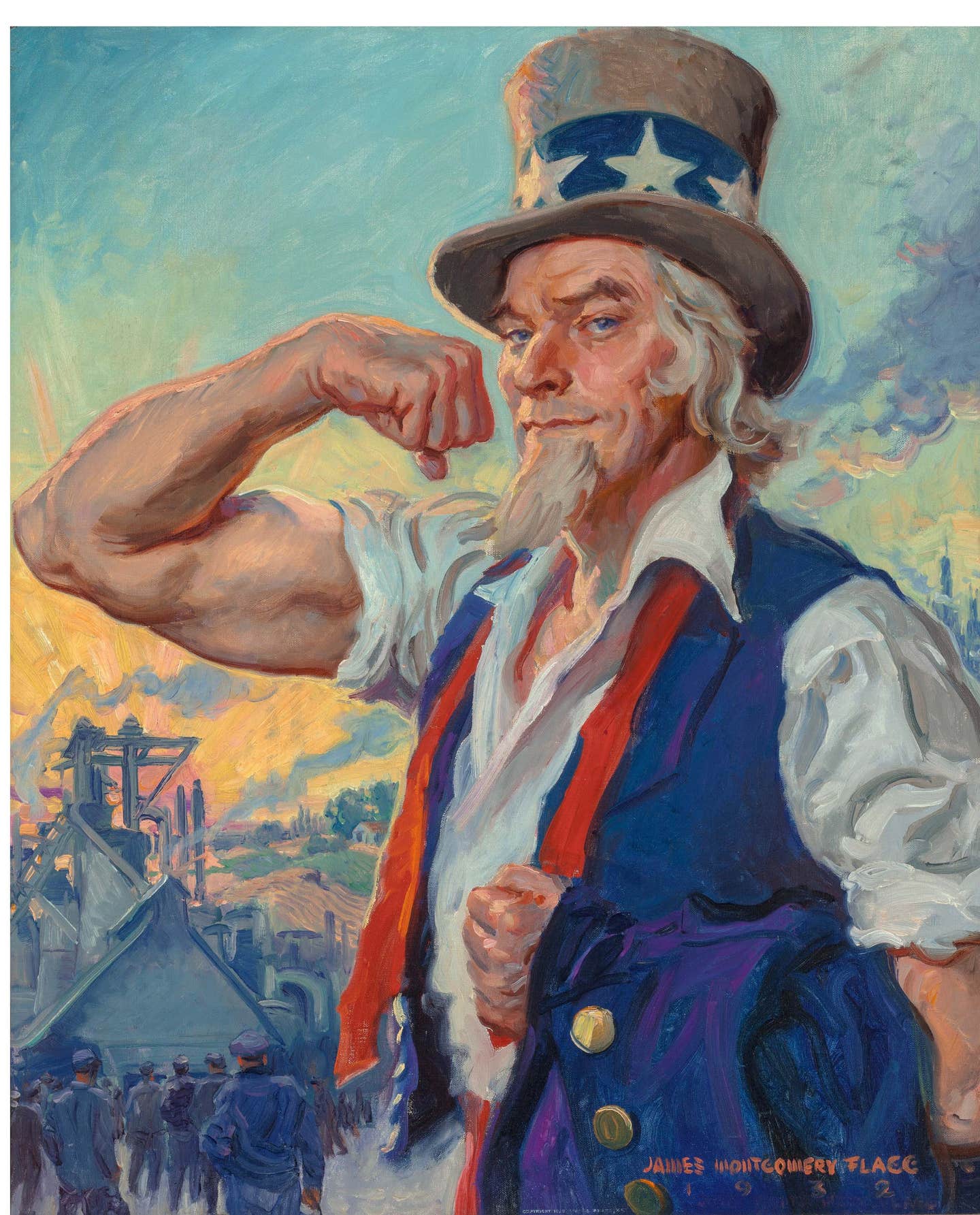

Flagg didn’t invent Uncle Sam but, with the top hat, goatee, the burning eyes and long finger pointing at the very soul of able-bodied men, he did transform him into a powerful and convincing figure. The poster struck a patriotic nerve with a staggering four million copies printed between 1917 and 1918.

Flagg, who had a healthy ego and was not afraid to share his opinion, called the recruiting poster “the most famous poster in the world.” Few could argue.

Of course, Flagg wasn’t the first to use convincing allegorical figures. That practice dates back to the Roman Empire. The Renaissance re-established the trend in Western art and culture by the 17th century. In the early days of the U.S., a female figure named Columbia (the name derived from Christopher Columbus) represented the nation. Columbia kept her role as an often-used symbol through the early 20th century.

There are several theories about where Uncle Sam comes from, but the most cited origin story traces him back to Sam Wilson of Troy, New York. Wilson delivered meat packed in barrels to soldiers during the War of 1812. Wilson was well liked and locals started calling him “Uncle Sam.” When folks saw Wilson’s supply barrels marked “U.S.” they naturally assumed the letters stood for Uncle Sam.

In reality, Wilson had labeled the barrels “U.S.” for United States. Soon the names became synonymous, with Uncle Sam becoming a symbol of the country. That version of Uncle Sam’s origin is so credible that Congress passed a resolution in 1961 adopting this account as the official history.

Uncle Sam started appearing in images and literature soon after the War of 1812. Thomas Nast, one of the country’s most well known political cartoonists, popularized Uncle Sam in the late 19th century. Even so, it’s Flagg’s powerful recruiting poster in 1917, the one asking YOU to join the army that crystalized Uncle Sam as a national character.

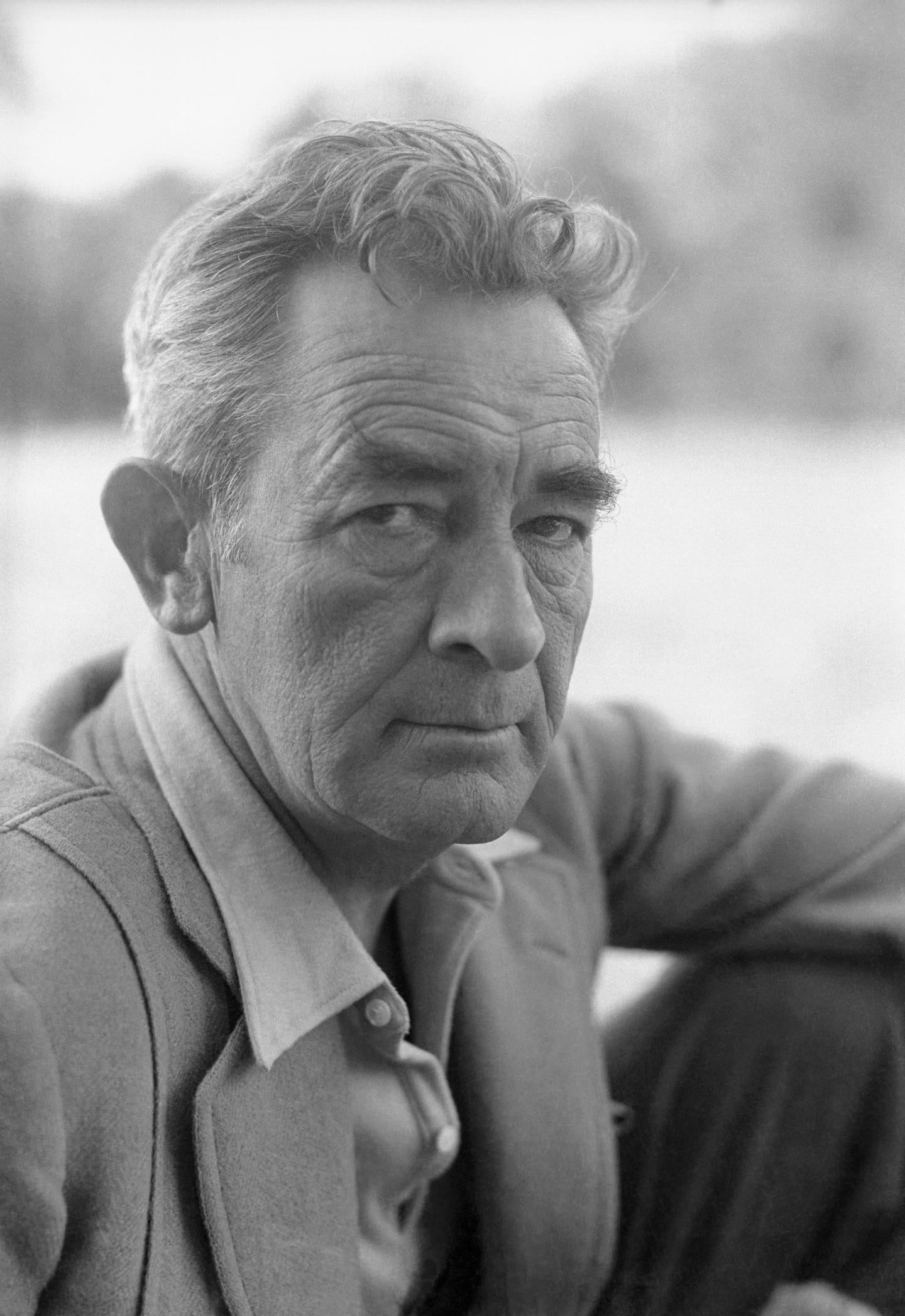

Born in New York in 1877, Flagg was a prolific illustrator, who – at the peak of his career – was said to have been the highest paid magazine illustrator in America. Flagg sold his first illustration at the age of 12. By 14 he had become a regular illustrator for Life, and two years later he joined the staff of its rival publication Judge.

Flagg was more than a boy wonder. He studied at the Art Students League in New York City (1894-1898) and then in London and Paris (1898-1900). During his career he created everything from cartoons, posters, magazine covers and inside illustrations and advertisements to serious portraits, which were exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1900 alongside the academic painters from the Académie Julian, a private art school for painting and sculpture in Paris. Besides Life and Judge, Flagg’s work was featured in Colliers, Cosmopolitan, Hearst’s International, Liberty, McClures Magazine, Photoplay, Redbook, Saturday Evening Post, The American Weekly, Women’s Home Companion, and many others.

Flagg was a favorite illustrator of publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst, leading to portrait studies of Hearst’s friends. Most were upper-class society scions and celebrities, including actor John Barrymore and his sister Ethel.

When American entered World War I, Flagg volunteered his illustrative skills to the Division of Pictorial Publicity (DPP) – a group initially established by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson. DPP used propaganda illustrations to promote the war effort. It proved so successful that it was quickly absorbed into Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information. At its peak, more than 300 illustrators volunteered their work, including the likes of Howard Chandler Christy, N.C. Wyeth and even a young Norman Rockwell.

Flagg produced 46 posters for the DPP’s war effort – many of them featuring Uncle Sam. During World War II, Flagg’s Uncle Sam reemerged and was found in front of every post office and recruiting station in the country.

But Flagg was no simple patriot. He was a bit of a playboy, an unapologetic fan of fast cars and beautiful women. Flagg enjoyed his work and the fame and fortune it provided. Flagg easily mixed with celebrities and earned a reputation for being one of the most colorful and cantankerous characters of his day.

Amusingly, Flagg even started to resemble his Uncle Sam character, using himself as his own model. Flagg was known to pose for press photos in full Uncle Sam regalia; something that won him admiration of Franklin Roosevelt who praised his resourcefulness, noting his methods suggested he had “Yankee forebears.”

But as the post-World War II era dawned, Flagg’s fame dimmed. The role of illustrators changed dramatically. They needed to work fast to adapt to the evolving world of mass markets and color photography. Flagg’s style fell out of fashion and his health faded, leaving him incapable of enjoying the gadabout lifestyle he favored. “I really died twenty years ago,” he said later in life, “but nobody had the nerve to bury me.”

James Montgomery Flagg died May 27, 1960.

Time is relentless and change steadfast, but history remembers, embracing Flagg’s most famous work, an Uncle Sam who unified a nation during its most desperate times.

Paul Kennedy is Editorial Director of the Collectibles Group at AIM Media. He enjoys Mid-century design, photography, vintage movie posters and people with a good story to share. Kennedy has more than twenty-five years of experience in the antiques and collectibles field, including book publishing. Reach him at PKennedy@aimmedia.com.