Bond-Style Stealth

These secret spy gadgets of the Cold War are super cool, and sometimes deadly.

When you think of the classic spy, you likely imagine a James Bond-esque gentleman in a sharp tuxedo, with plenty of weapons in his arsenal.

When Bond needed nifty espionage gadgets, like false fingerprints, a Rolex-turned-circular-saw or bagpipe flamethrower, he counted on the British Secret Service. When American operatives needed to snap photos on the down-low or transmit a secret code, they had the Central Intelligence Agency’s Office of Research and Development working the tech angles, and Russia had the KGB creating an arsenal of tools.

Plenty of spy devices were invented before the Cold War, however. The Spartans and Greeks used their own form of 007 gadget invented in 500 B.C. called scytales — cylinder-shaped tools wrapped in parchment or another available material that contained messages that needed to be communicated during military campaigns. Codes could be deciphered by placing the material over a rod of similar size. Other gadgets throughout history include the Alberti Cipher, invented in 1466 by Italian painter and architect Leon Battista Alberti and thought to be one of the first polyalphabetic ciphers ever created; sympathetic stain (1778), invisible ink developed by Dr. James Jay that consisted of one chemical used to write a message and another to decipher it, and was reportedly used by George Washington; a “coal torpedo” (1864) developed by the Confederate Secret Service that consisted of a hollowed-out iron casting filled with explosives and painted to look like a piece of coal; and in the 1940s, playing cards and Monopoly were used throughout World War II to hide secret information; embed secret maps were put into cards, which were later soaked to split and reveal the map, and fake Monopoly sets, distinguished by a red dot located on the “free parking” space, contained files, maps, and compasses.

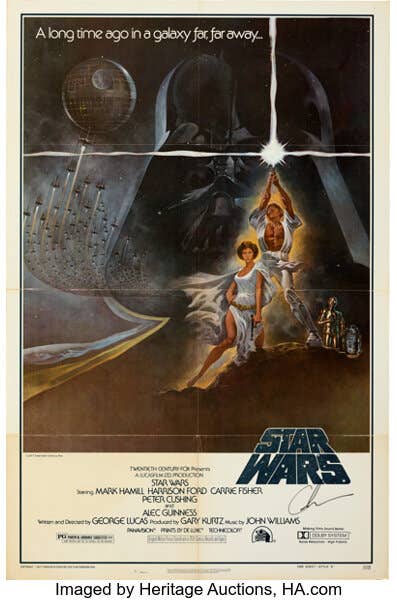

But during the Cold War (1947-1991) is when spying really started heating up and gadgets became more interesting. Besides James Bond reigning at the movie box office, “I Spy,” “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” and “Get Smart” were top-rated TV shows, and “Secret Agent Man” topped the pop charts. Pop culture of the 1950s and 1960s was steeped in trench coats, tiny cameras and espionage.

While Hollywood romanticized the whole image of espionage, the real thing was far from romantic. It was a dangerous cat-and-mouse game that could result in death, whether by assassination or agents killing themselves with poison before secrets could be extracted from them by the enemy. As the United States and Russia maintained a frigid relationship framed by the specter of nuclear war, agents around the globe plotted to snag intelligence from the two superpowers. Spies had to prepare themselves for the worst, and their ability to blend with their surroundings was vital to their survival.

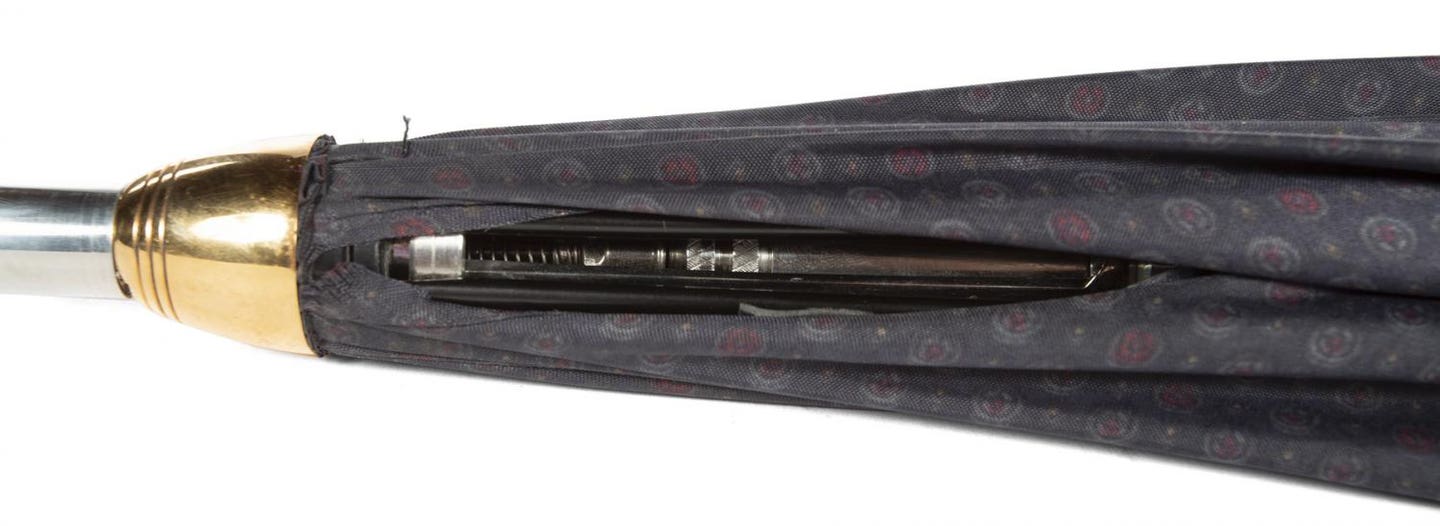

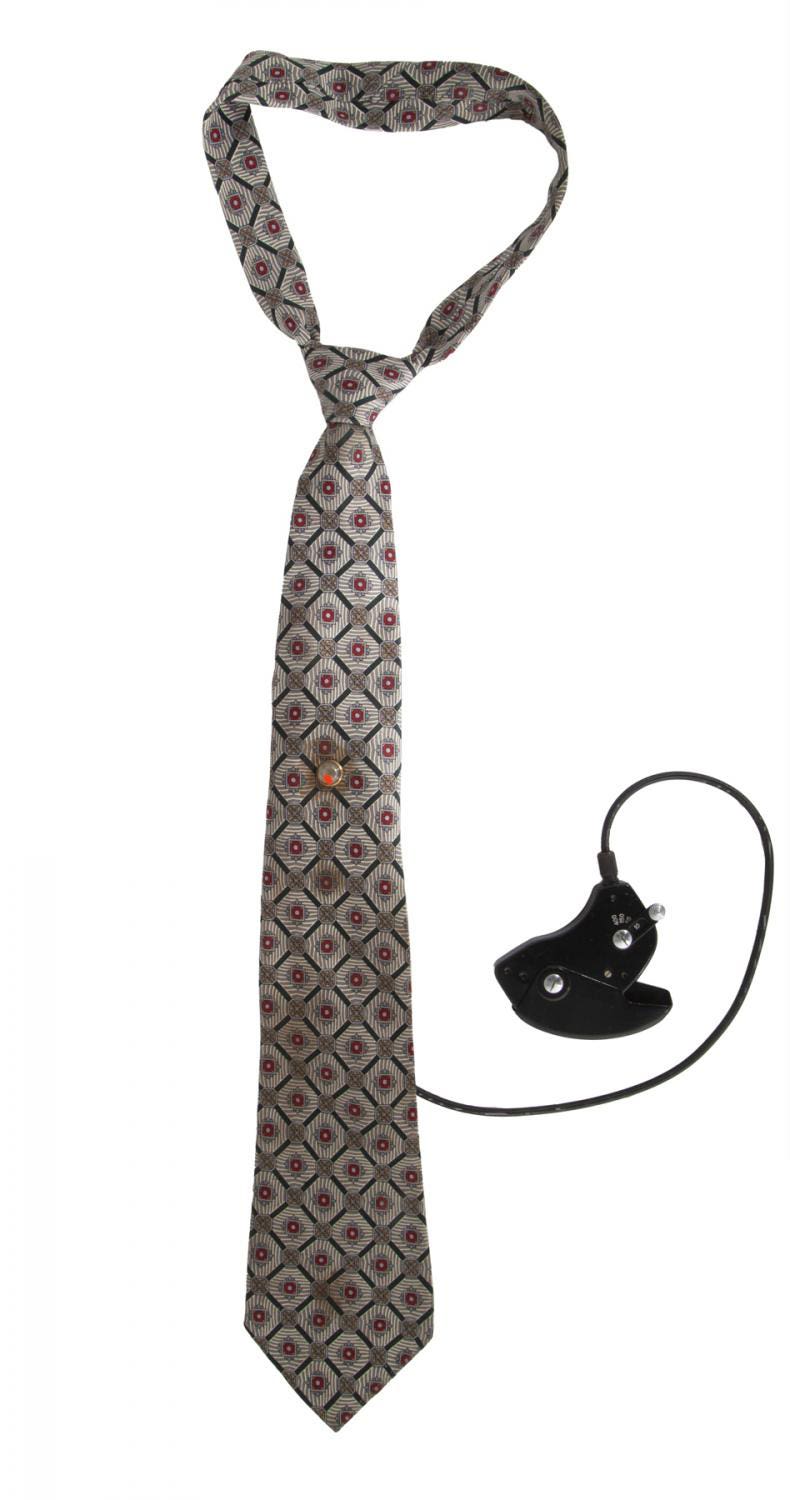

The USSR and the U.S. spent large amounts of money training, recruiting, outfitting, and deploying spies all around the world, which resulted in many technological innovations. While many of these tools may seem quaint in the era of cell phones, high-tech hacking and the battle to keep encrypted information safe, tiny cameras, desk-top decoding machines and deadly devices including fake teeth and umbrellas that hid cyanide and ricin were among the surveillance weapons of the day.

Although the CIA’s Langley Museum isn’t open to the public, nearly 200 Cold War spycraft artifacts can be explored via its Flickr account.

The International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., is open to the public and exhibits include Spies and Spymaster and Tools of the Trade. Tickets for in-person visits can be bought at its website and a virtual tour, as well as other virtual events, are offered.

The entire collection of New York City’s KGB Espionage Museum, which was forced to close after major losses due to COVID-19, was recently sold by Julien’s Auctions.

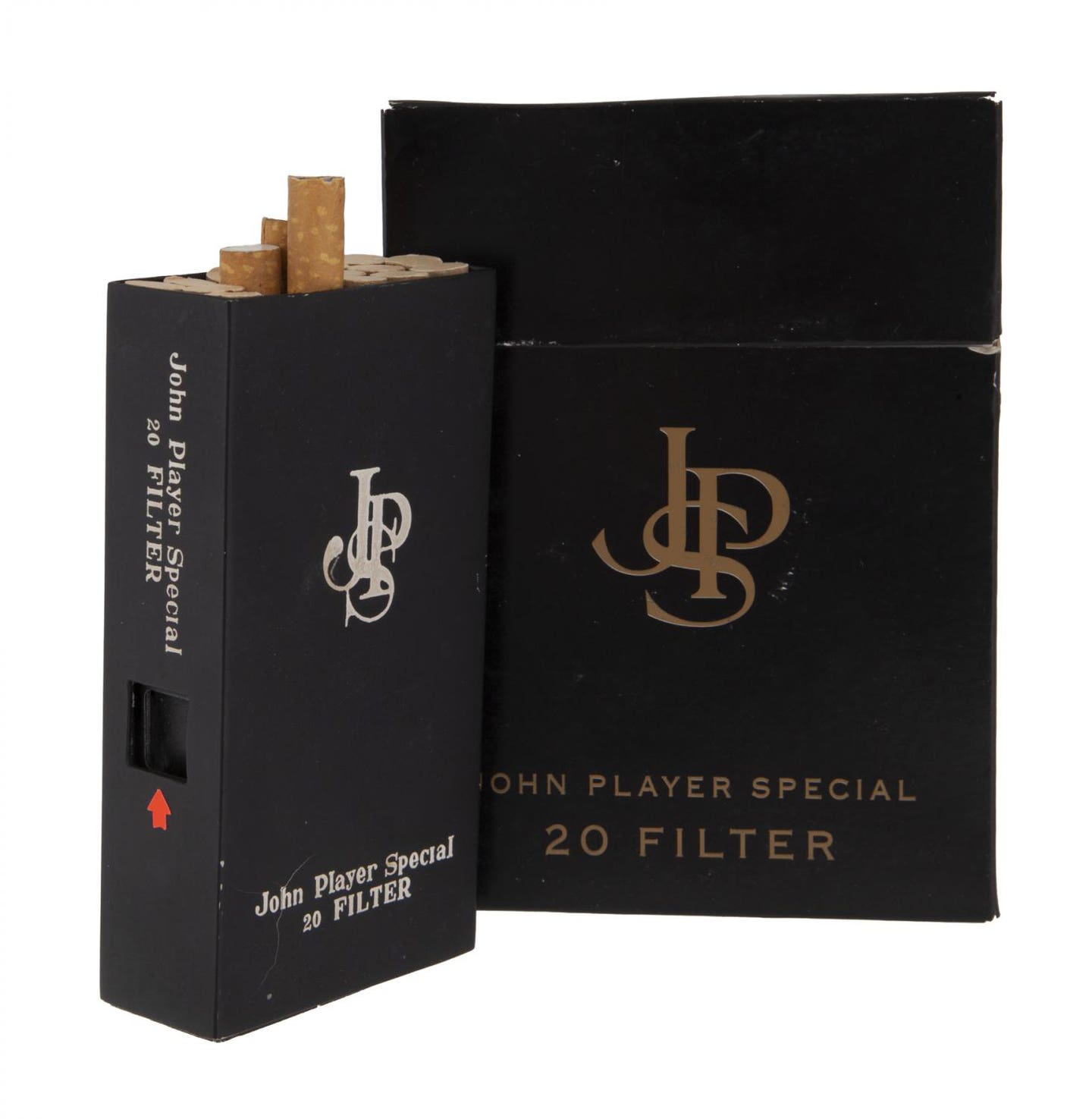

Over 400 lots were offered and included clandestine operative cameras and wiretaps tucked into in everything from packs of cigarettes and rings to a purse, dinner plate, ballpoint pen and belt; counter-intelligence detectors, Morse code machines, airplane radars, voice recorders and official government documents, and a gun designed to look like a tube of lipstick. Many sold for thousands above their estimates. An archive of items sold can be found here.

The collection was procured by world-renowned historian, collector and museum curator, Julius Urbaitis, who worked as the consultant for the 2019 Emmy and Golden Globe award winning HBO series, Chernobyl.

Another museum Urbaitis maintains, the underground Atomic Bunker, is in Lithuania and online.

Featured in the gallery below are some highlights from the auction and the CIA and International Spy museums.