A Toast to Butter Art

The original dairy queen, Caroline Shawk Brooks, became the nation’s first butter-sculpting sensation in the late 1800s.

Butter sculptures are common attractions at state fairs, especially in the Midwest, and with June being National Dairy Month, we’re celebrating the first superstar of butter sculpting: Caroline Shawk Brooks.

Butter as a sculpting medium can be traced back to “banquet art,” a tradition most associated with the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It was a way of bringing entertainment to the table for special occasions and to impress guests. The earliest reference to the practice dates from 1536 and details the creations of Pope Pius V’s cook, including an elephant and a tableau of Hercules engaged in combat with a lion.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, dairy farmers expressed their creativity through creamery by pressing their butter into butter molds, usually carved from wood, to add panache to their product while also offering their customers a way to identify it, especially important as dairy began to be sold at the market and not directly from the farm.

The Cincinnati-born Brooks (1840–1913) elevated this considerably when she began sculpting the butter instead of pressing it in a mold. She was the first known American sculptor working in the medium of butter and became known as “The Butter Woman.”

Brooks sculpted her first creation out of butter in 1867, when the cotton crop on her and her husband’s farm failed. The 19th century was an era that valued ingenuity and resourcefulness, so if you were an artistically inclined Arkansas farm wife without access to modeling clay but performed the daily chore of butter-making, you did what Brooks did: used what you had.

Brooks sculpted the butter into shapes including shells, animals, and faces as a new way to promote their dairy product and also as a source of supplemental income. Rather than traditional sculpting tools, she used common butter-paddles, cedar sticks, broom straws and camel’s-hair pencils. Her customers appreciated the skillfully sculpted butter, and there was a good market for her works.

In 1873, Brooks created a bas-relief portrait, which she donated to a church fair. Her husband safely transported it, on horseback, the seven miles to the fair, and the sale of the portrait earned the church enough money to fix their roof. A Memphis man who saw Brooks’ work there admired it so much that he arranged for her to create a butter portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, to be displayed in his offices.

That same year, she also created a sculpture of the blind princess Iolanthe from Danish poet and playwright Henrik Hertz’s verse drama, King René’s Daughter. “Dreaming Iolanthe,” as it was known, was exhibited at a Cincinnati gallery in 1874 for two weeks and attracted more than 2,000 people who paid 25 cents each to catch a glimpse of the sleeping princess rendered in a dairy product. Continuing on the same subject, Brooks made a bas-relief bust of Iolanthe for the Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia in 1876, which was also an instant hit and preserved over a bucket of ice that required constant replenishment.

According to Pamela Simpson’s book, Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture, the sculpture was “repeatedly praised as ‘the most beautiful and unique exhibit at the fair.’ ”

An article appearing in The New York Times declared that the “translucence (of the butter) gives to the complexion a richness beyond alabaster and a softness and smoothness that are very striking,” and that “no other American sculptress has made a face of such angelic gentleness as that of Iolanthe.”

Brooks also made a full-sized sculpture that was shipped to France and exhibited at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878. She reportedly found it amusing that customs officials had listed her sculpture not as a work of art, but as “110 pounds of butter.”

Working with, transporting, and exhibiting butter sculptures presented Brooks with a unique set of challenges. To preserve her delicate butter sculptures, she created them in flat metallic milk pans which she set in larger pans filled with ice. By continuing to supply the outer pans with ice, she was able to keep her butter sculptures in good condition for months. When attempting to sail from New York to France with a life-size butter sculpture, she was forced to delay her departure until she was able to secure passage on a ship with sufficient ice to preserve her work throughout the journey; and then she faced the task of finding a railroad car which also had enough ice to safely transport the piece from Le Havre to the final destination of Paris.

Brooks was said to prefer butter over clay as a molding medium. Clay had to kept moist and wrapped to prevent it from cracking, was not as sensitive for sculptural manipulation, and was more difficult to cast. Brooks had conquered the major disadvantage of butter simply by using ice.

Brooks went on to study art in Paris and Florence, and although she later tended to forgo dairy for the more traditional medium of marble, she always continued to use butter as a material.

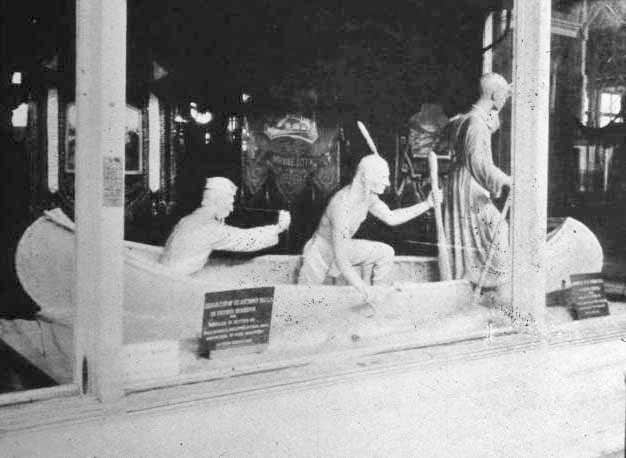

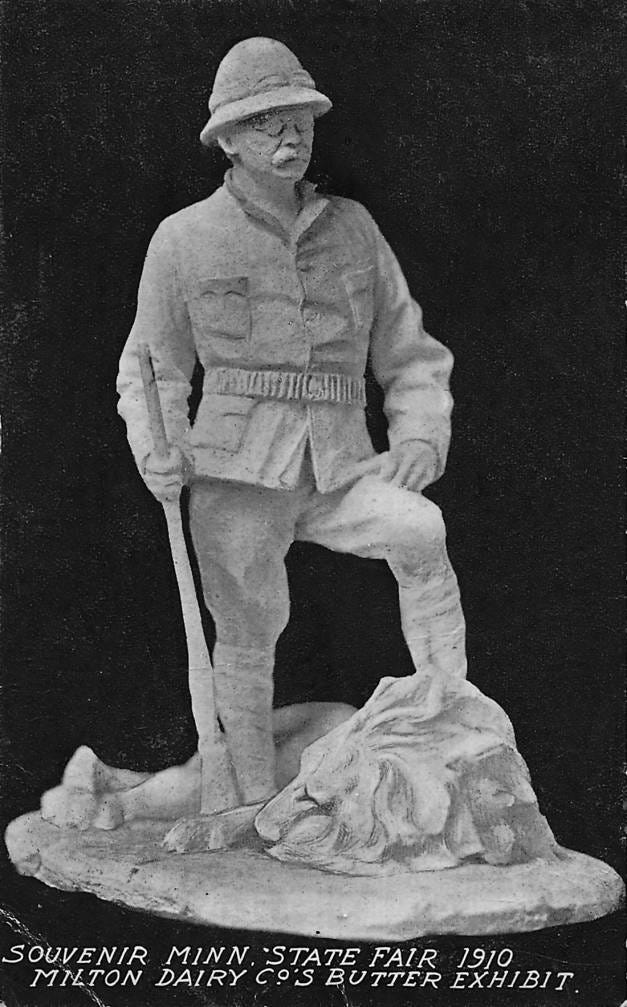

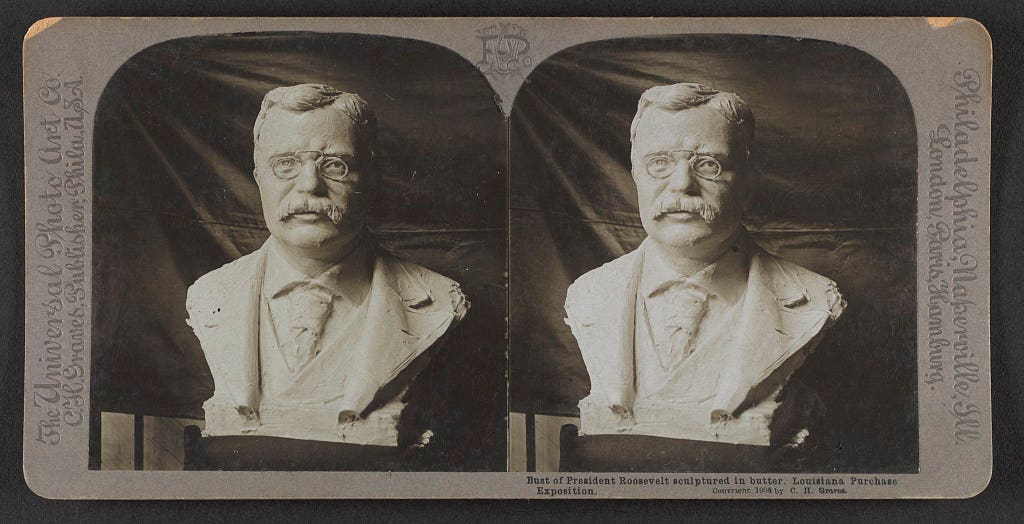

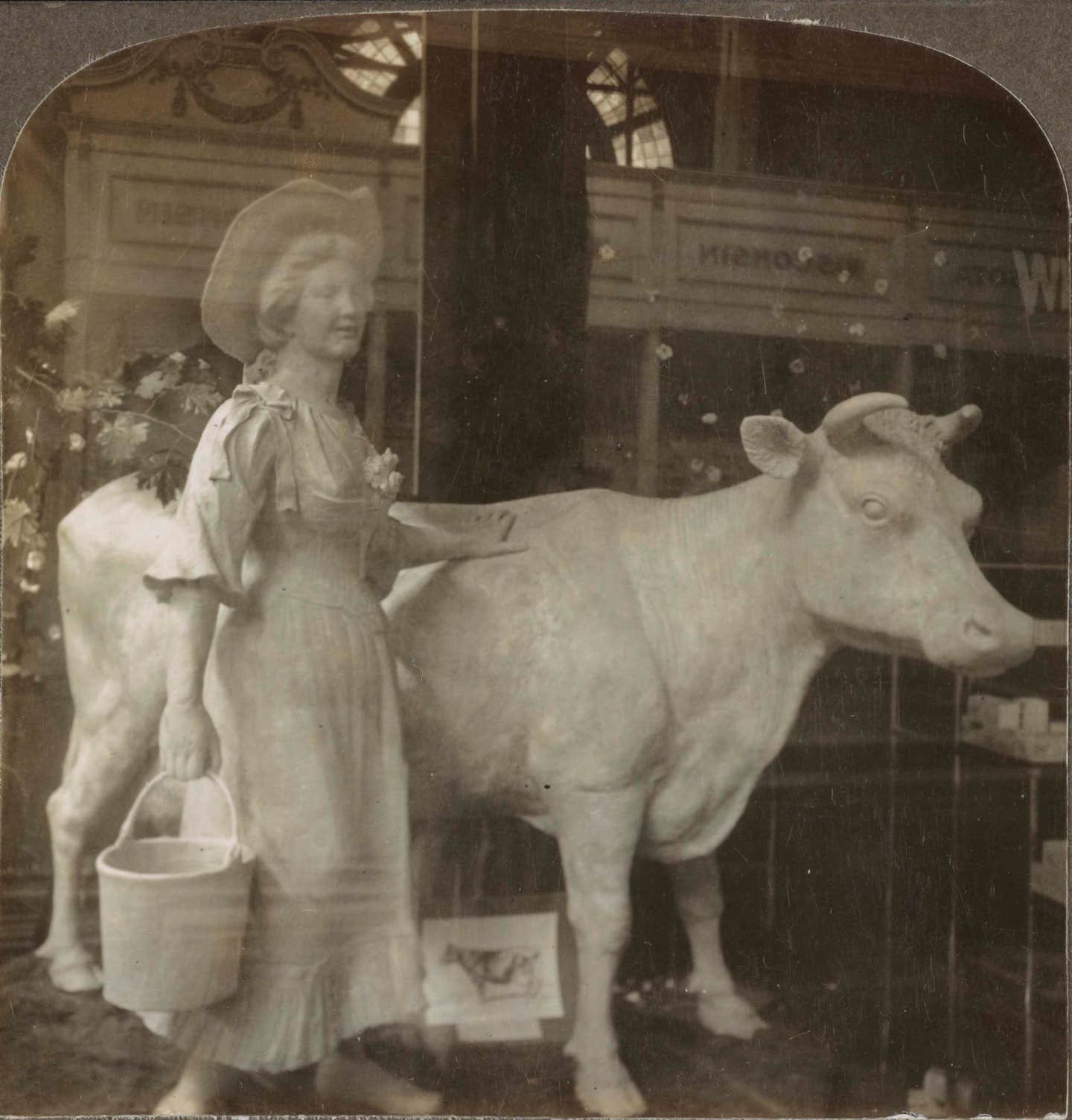

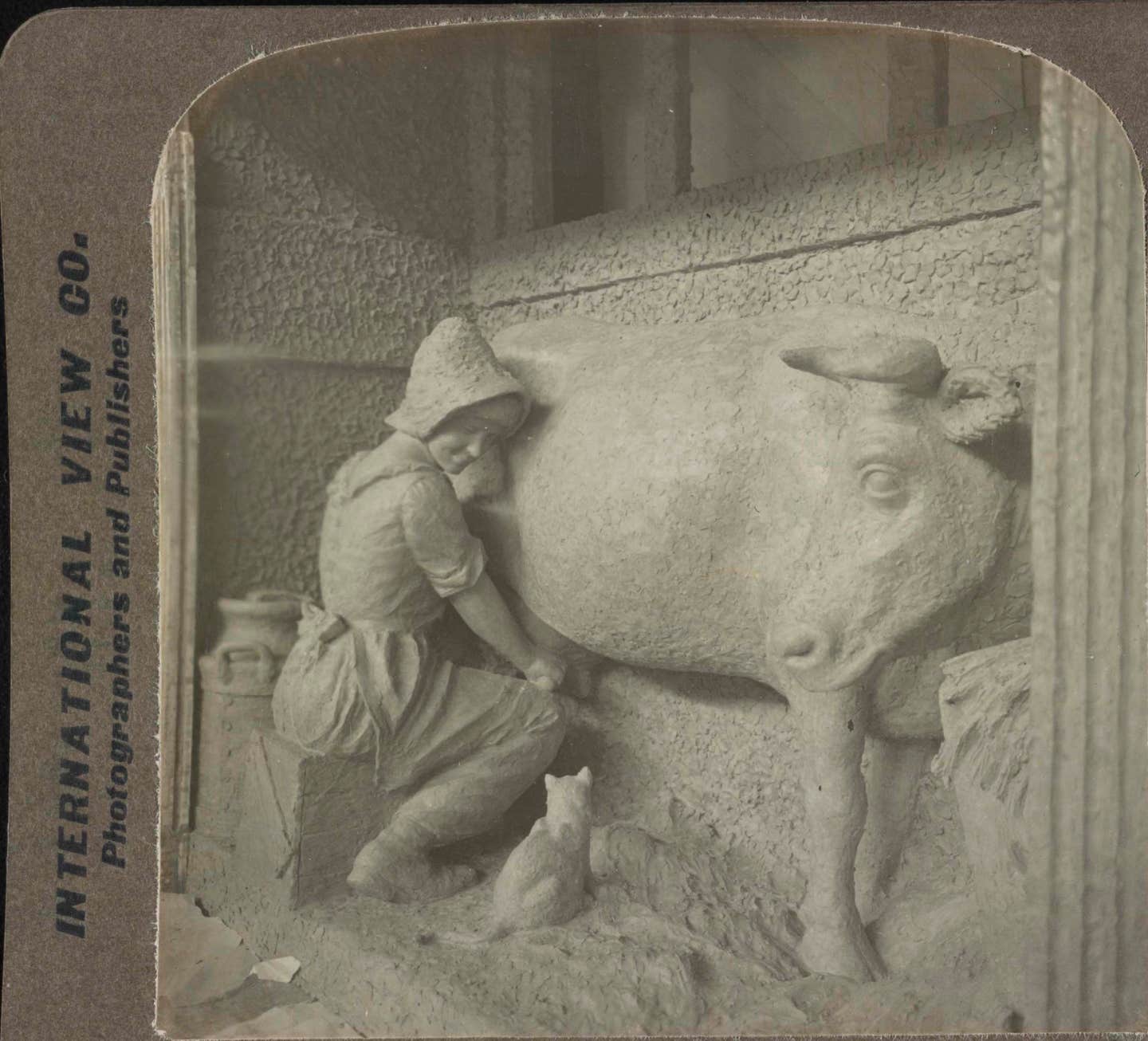

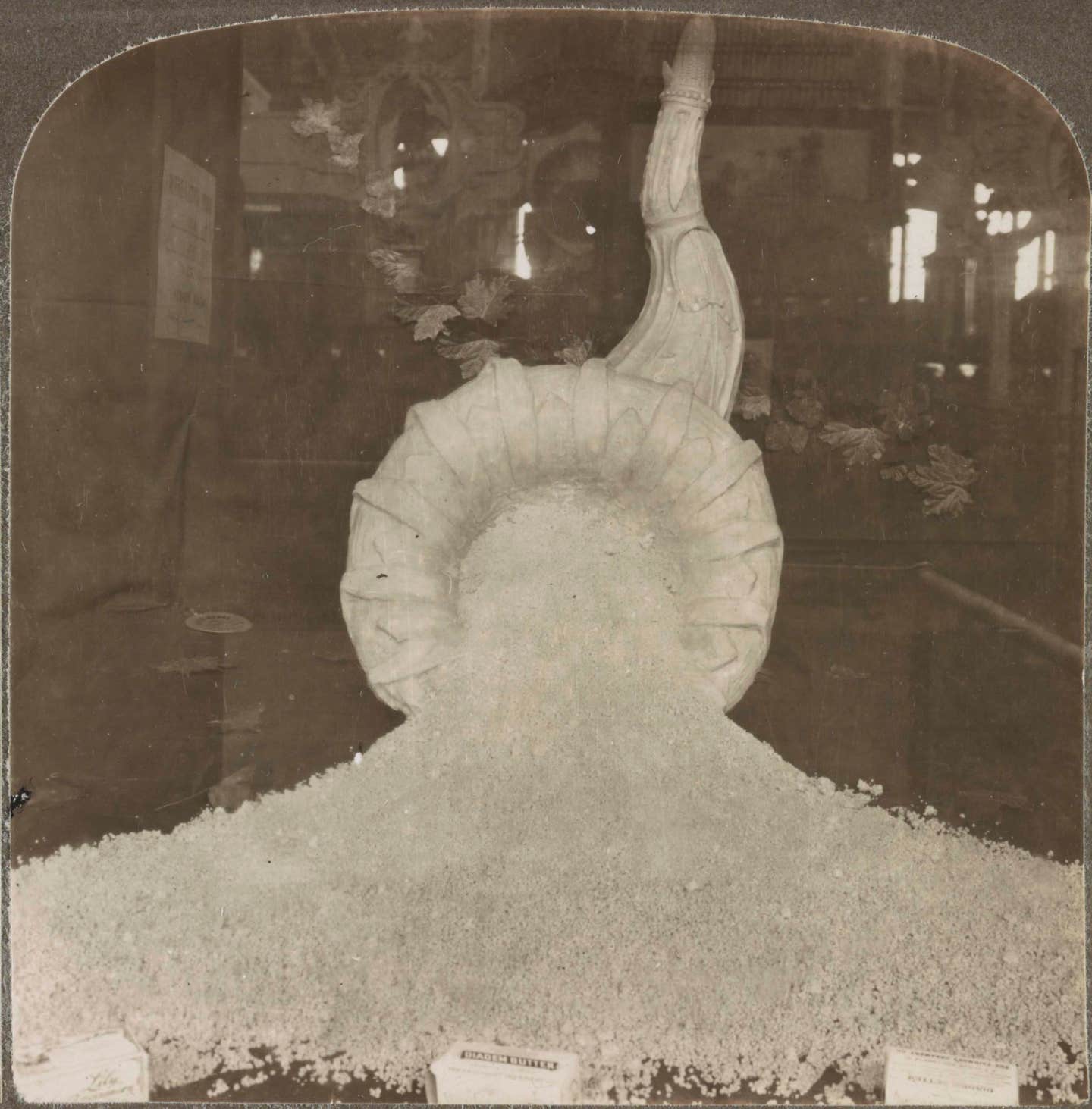

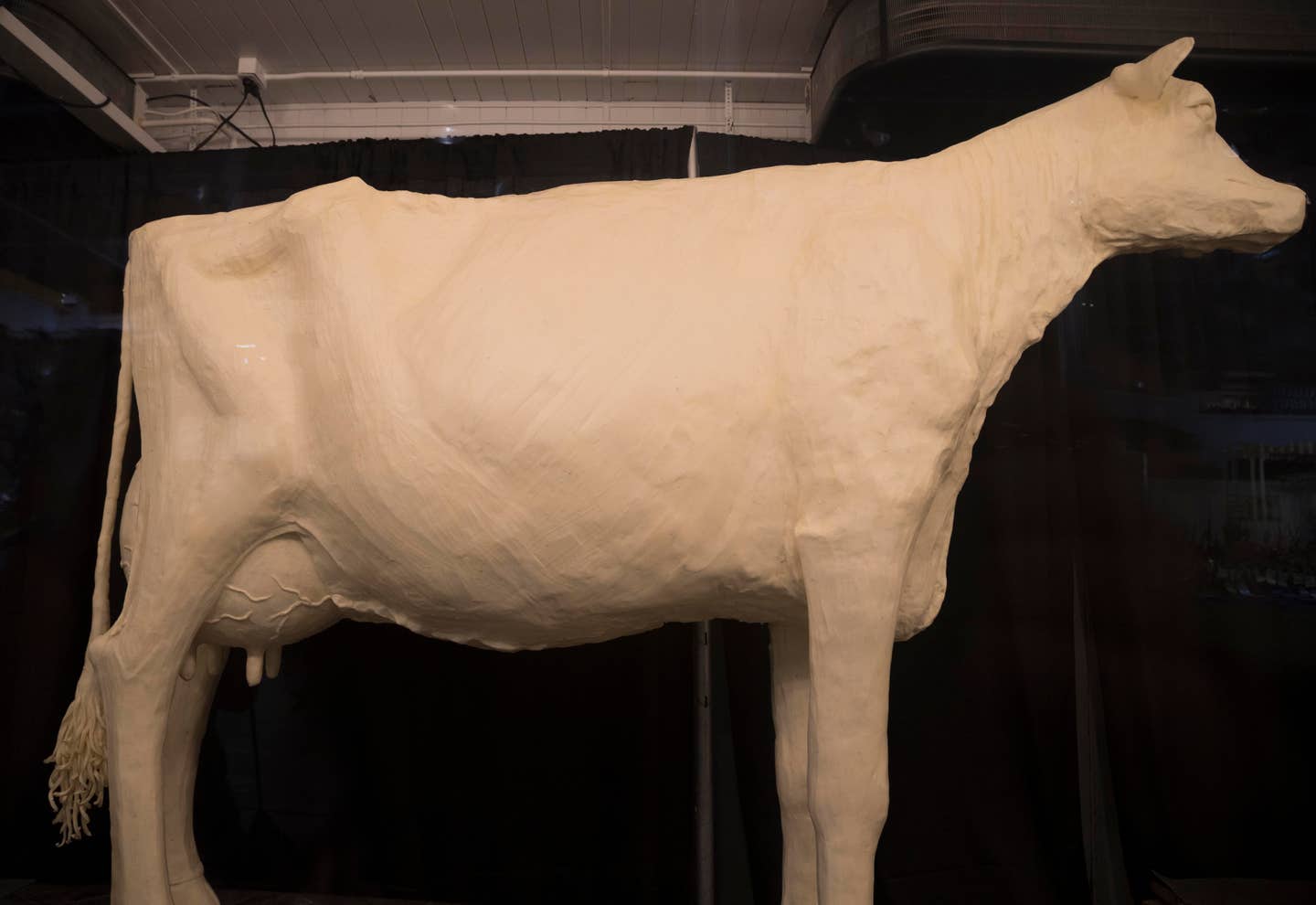

At the 1904 St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition, butter was big. Several states chose to bring large butter sculptures with them — including a scene of a goddess, steer, and bear by California — but Wisconsin eclipsed them with a 600-pound statue of a milkmaid milking a dairy cow. It was only outmatched by Minnesota, which commissioned a Norwegian-American sculptor named John Daniels to create a tableau of a missionary, Father Hennepin, seated in a birch bark canoe with two Native American guides. He also sculpted Teddy Roosevelt. Some of this butter work is featured in the photo gallery below.

While other people were inspired by Brooks to create their own butter displays, almost all of them were done in conjunction with commercial butter interests and dairy associations for promotion of their products at fairs and expositions. Brooks dedicated her work to the creation of butter art purely for its artistic merit.