Use the proper search terms to identify an artist

Dr. Anthony Cavo takes us on his journey to identify the artist of an unsigned oil painting after buying a ‘love-it-or-hate-it’ depiction of King Lear.

By Dr. Anthony J. Cavo

About fifteen years ago I attended an auction with my sister in a small town in southwestern Massachusetts. I still remember everything I purchased at that sale including an Empire two-drawer work table, a religious oil on canvas, a French five-drawer till, a mid-eighteenth century blanket chest with candle box, bracket feet, two drawers and tulip strap hinges and finally, another painting.

Much of the painting’s details were obscured by many years of dirt and darkened veneer, nevertheless, what was visible was intriguing and I decided it was something on which I would bid. The painting didn’t garner much attention during the preview, which is always a hopeful sign that an item might not sell well.

The sale progressed and late in the evening with almost all lots sold, the painting hadn’t yet crossed the block. I requested it from one of the runners who returned about ten minutes later to say the painting could not be located.

I immediately smelled a rat – you often find them at auctions. These rats remove finals, pulls, lids and most often keys and pendulums from clocks as well as furniture keys all in an effort to reduce the amount someone is willing to bid. I conducted my own search and within ten minutes or so found the painting stashed behind a large piece of furniture. Because of my experience as an auctioneer, I was familiar with this old trick.

In an uncatalogued auction, people sometimes hide items only to retrieve them at the end of the sale when the auctioneer invites people to bring up any unsold items they wish to bid on. The motivation behind this strategy is to bring an item out as late in the auction as possible when much of the crowd (the competition) has already left.

The auctioneer didn’t think much of the painting and made a crack about a dumpster. The bidding started at $25 then rapidly moved up into the hundreds with only one other bidder – the rat. The bidding continued until he bid $450. I bid $500 and he reluctantly lowered his Sharpie-numbered paper plate.

The surprised auctioneer called out “all in, all done” before the gavel went down and the painting was mine. I was excited; my sister not so much. She simply smirked and walked away shaking her head.

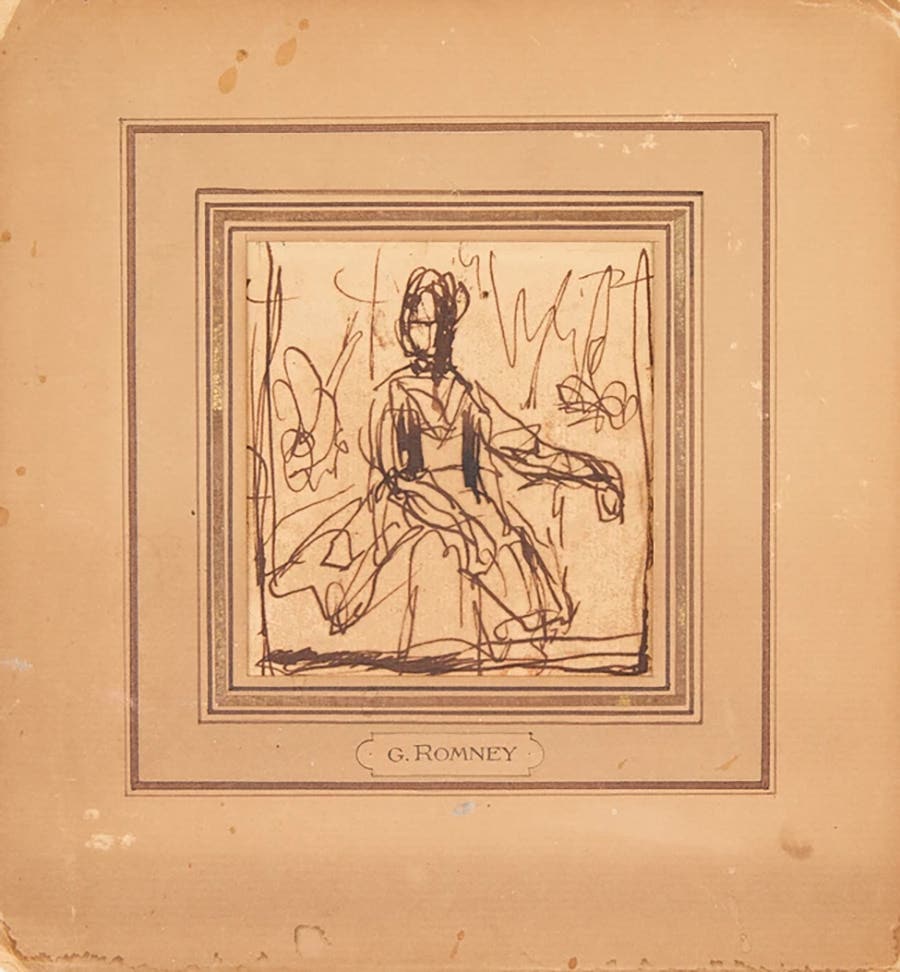

The painting is one you either love or hate and upon seeing it people either smile or sneer. I get butterflies. The painting depicts a crazed looking old man being embraced and kissed on the cheek by a jester. I quickly dubbed it “King Lear.” (Who knew reading all that Shakespeare in high school would pay off?)

Tools used in the search

I was unable to find a signature but knew that one might be obscured by the darkening that came with age. So I searched every square inch in sunlight, bright light and black light but no signature was revealed. I photographed it with a raking flash, which revealed most of the detail beneath the veneer, but still there was no sign of a signature.

Unless you are an expert on a particular artist it is difficult to absolutely and confidently identify a painting as the work of that particular artist. You can evaluate the overall style, examine paint strokes, and rely on science by performing objective tests that include microscopy, chemistry and infrared reflectography.

Paint layers can be examined for signs of aging by using a microscope to evaluate the amount and depth of craquelure and to determine if the crazing is natural or artificial. Characteristics of pigments can also be studied with the aid of a microscope and chemical analysis. A Woods light, the same light used in medicine to examine skin for infections and eyes for foreign bodies and corneal abrasions, can be used to determine if a painting has been restored and to what extent it has been touched up or overpainted or if a signature was added at a later date.

Infrared examination can also identify areas of restoration and underpainting known as pentimenti. The finding of pentimenti indicates there is another painting or drawing beneath the visible image – this may signify the re-use of a canvas or revision of the artist’s earlier work.

Glue, pigments, varnish and canvas can be studied with infrared spectroscopy to establish their consistency with the time period from which they are believed to originate. Infrared spectroscopy can also be used to examine and date the wood of the stretcher.

Access to the tools required for such scrutiny is not available to the average person who must rely on what they know and what they are able to learn. I knew the painting was old and that was all l knew for sure. The crazed looking old man and the jester suggested it may be a depiction of King Lear and the jester; however, the jester seemed like one I’d seen in a painting by the famous Polish painter, Jan Matejko.

Painting by Polish artist Jan Matejko?

I fixated on this similarity to the exclusion of any other consideration. I became the doctor who diagnosed a disease then tried to make the symptoms fit. My open mind closed, my sight was restricted to tunnel vision. I made up my mind this painting was done by Jan Matejko and I attempted to prove it. In this pursuit, I contacted Jan Matejko experts in Poland who initially shared my enthusiasm upon receipt of the images. Expert after expert, art dealer after art dealer quickly lost interest when I was unable to provide a signature.

Soon my own interest waned and the painting was once again relegated to a place behind a piece of furniture. Every so often I would research paintings and painters of King Lear and the jester.

I also revisited the works of Jan Matejko, still convinced that the jester in his painting Stańczyk was a match for the jester in my own painting; the hat was the same, the nose was the same, the zygomatic arch (a five-dollar word for cheek bone) was the same. I was the detective who selected his suspect then tried to make the evidence fit rather than the other way around. Becoming bogged down by opinions based on nothing more than hope amounts to a waste of time.

I put the painting back behind the desk where it remained until September 2018, when I re-examined it with a loupe and black light inch-by-inch. New photos were taken and sent to two more experts in Poland who again asked if there was any evidence of a signature. I was determined to prove this was the work of Jan Matejko.

The search continues

This time, however, I decided that instead of researching oil paintings I would research illustrations knowing that artists often drew a number of studies prior to executing a painting. I also knew that many 19th century paintings were published as engravings in newspapers, books, and periodicals.

I performed an online search using the keywords, “Illustration,” “King Lear” and “Jester” with much the same results as before.

My nephew, a senior in high school, informed me that I should actually be searching for “King Lear and the fool.” I took his advice and within minutes an engraving of my painting was there before me in The Aldine, Vol. IX, No. 6, The Art Journal of America 1878.

After fifteen years of searching it took only a few minutes (and advice from a high school student) to identify this painting. I also had to jettison my groundless beliefs and start at the beginning.

Instead of initiating a search with the name of the artist I thought it might be I began a new search with a simple, more realistic, rational approach and it worked.

The artist is found

The painting, it turns out, is not by Jan Matejko nor is it from Poland. The painting was done in Germany by Gustav Schauer, an artist with works in a number of museums including: The Getty Museum, The National Museum of Sweden in Stockholm, The National Gallery of Canada, The Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels, The Municipal Museum of Leipzig, The National Portrait Gallery and others. Gustav was a painter who today is more widely known for his photography.

The one thing I did have almost correct was the title: King Lear and the Fool, which The Aldine called, “his first great painting.” The painting was done in 1876 and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Berlin in 1878.

Finally, the search was over and the lesson learned was that while hunches are a great place to begin a search, you have to consider your hunch may be incorrect and to use facts rather than unsupported conclusions; you have to start with “A” to get to “Z”. Now, after 140 years of dirt and grime, the painting is finally going to be cleaned and restored.

“The ox is slow, but the earth is patient,” thanks Confucius.

AntiqueTrader.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.