The Madame Tussaud of America

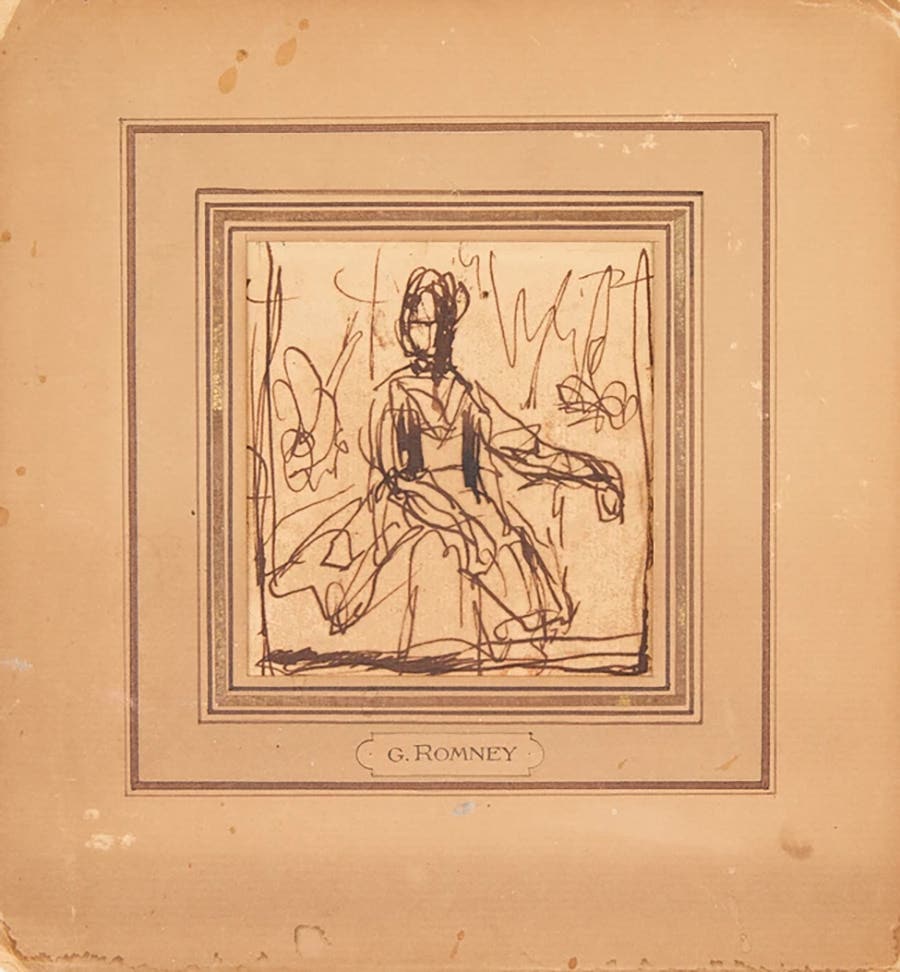

Recognized as the country’s first sculptor, Patience Wright’s wax portraits were ahead of their time.

With the sudden death of her husband, barrel maker Joseph Wright, in 1769, Patience Wright found herself in a financially dire state. With four children to support — some young enough to cling to her apron strings and another due soon — she was hard set to secure an income, so she turned her hobby of creating wax portraits into a full-time livelihood.

Considered America’s first sculptress, Wright was often referred to as the Madame Tussaud of the American Colonies. Wright, whose wax work preceded Tussaud’s by thirty years, created portrait busts in tinted wax, and many of her documented works were highly detailed, full-sized heads and hands that she attached to fully clad figures. Her wax art also led her to her brief stint as a spy during the American Revolutionary War.

Patience Lovell was born in 1725 into a prosperous Quaker family on Oyster Bay, situated on Long Island in New York. In 1729, the Lovells moved to Bordentown, New Jersey. Wright’s talent for sculpting appeared early on. Together with her sisters, she molded wet flour or clay into small sculptures; once dry, they applied paint made from plant extracts.

Wright felt restricted in the strict confines of her parents’ Quaker household, and rebelliously left and struck out for Philadelphia. It was there on March 20, 1748, she married Joseph Wright, who was quite a bit older. At the time of her husband’s death, Wright was forty-four years old. A widow in dire straits and without resources, she moved back to her family home in Bordentown and with her sister, Rachel, launched a waxworks house in Philadelphia and one in New York City by 1770.

In Wright’s day, the only images captured of people were through painted portraits or sculptures, but Wright became proficient in her wax craft and soon her reputation spread throughout the region. Wright’s clients would sit for long periods of time while she sculpted their likenesses in wax. While engaged in conversation with her customers, she worked the wax into formed heads and torsos onto which she would meticulously inset glass eyes, paint the lips and cheeks, and even attach minute sets of eyelashes to achieve the most realistic look.

Wright’s wax portraits were the first documented efforts of “sculptural expression” in the American colonies. The demand for her creations soon gained flight in her studios in both New York and Philadelphia, where they were displayed. But fate dealt her a heavy blow. The New York waxwork on Queen Street, more lucrative than the Philadelphia house, was destroyed when fire ravaged the entire block of structures in June 1771 — her entire inventory of work was destroyed. Once again, Wright was left in dire straits.

In 1772, she decided to cross the Atlantic to London. In February of that year, she boarded the packet, the Snow Mercury, alone. Later her children would follow. A fortuitous encounter with Jane Mecom, the sister of Benjamin Franklin, gave Wright an introduction to the elite of 1770s London. The medium of wax was considered by some as a practice of “low art” when compared to sculpture in bronze or stone. But once in London, she soon discovered that her wax creations were in celebrated demand. It didn’t hurt matters that she was also carrying a letter of introduction from Dr. Franklin.

Wasting little time, Wright was soon sculpting in wax the “faces of lords, ladies and members of Parliament” and created a popular exhibit of wax models. Londoners were not quite ready for this spontaneous “Promethean modeler” in wooden shoes, and who planted kisses on both cheeks of everyone she met — no matter what sex or which class they belonged to. One newspaper reported on “the ingenious Mrs. Wright, whose skill in taking likeness, expressing the passions, and many curious devices in wax work, has deservedly recommended her to public notice.”

Wright’s unconstrained style shocked some, but was not wholly looked down upon. Her straightforward prose and unfettered openness, in combination with her craft, dissimilar from any creative work hitherto seen, transported Wright into the realm of a singular eccentric. Some reported she even addressed the king and queen as “George” and “Charlotte,” when they sat for her. One of those within the royal’s circle noted the “vigor and originality of her conversation.” Many of Wright’s clients were members of England’s uppermost ranks, and the plainspoken praise she heaped on them was well received.

It is reported that with the start of the American Revolutionary War, Wright was privy to information while in London that was helpful to the American cause, and she passed on this intelligence that warned of the intentions of the British. One plausible narrative tells that the details she gathered were hidden in the wax figures that she sent to her sister in Philadelphia. Wright would pass letters hidden in wax heads, busts, and buttons.

According to reports in American newspapers, Wright forcefully scolded her noble patrons on their mistreatment of the American colonies, and this tactic soon brought the disfavor of her English hosts. Her name appears in no British newspaper after 1776, and her audiences with the royal family were almost certainly cut off as she refused to conceal her political agenda. Legend has it she scolded the king and queen after the battles of Lexington and Concord, her stridency shocking all present.

Wright traveled to Paris in 1780, in hopes of opening a waxwork studio, but it wasn’t to be, and she returned to England in 1782. Once there, she moved into the home of her daughter, Phoebe, and her son-in-law, painter John Hoppner, at St. James’s Square. In 1783, Wright penned a letter to Founding Father John Jay stating her intent to create wax busts of not only Washington, but the other Founders as well: “I wish for nothing more than to finish the portraits in wax busts of all you worthy heros that have done honour to themselves and their Country by their Wisdom, their Valour, and good Council.”

Homesick for America, and excited about the opportunity to sculpt a life-size figure of George Washington, as he had agreed to sit for her, Wright decided to return to New Jersey, but before she could set out for America, she passed away on March 23, 1786. Wright was buried in London, but the site of her grave is unknown.

Wright’s artistic skill was so adept and the wax models of faces she created were so akin to the original, that many of those observing her work were taken in. Wright could claim to have created the most famous heads of her day and there are a number of her wax miniatures that have survived, but of her full-size figures, only one of William Pitt remains.

Sources:

“A Woman of Wax,” Emmons County Record (Linton, North Dakota) December 1, 1910.

“From George Washington to Patience Wright, 30 January 1785,” National Archives.

“Patience Wright,” www.bordentownhistory.org.

“Patience Wright; American Artist,” Encyclopedia Britannica.

“Patience Wright,” The Crayon, Vol. 2, No. 11 (Sep. 12, 1855), pp. 163-165.

Serratore, Angela, “The Madame Tussaud of the American Colonies Was a Founding Fathers Stalker,” smithsonianmag.com, December 23, 2013.