Diego Rivera began drawing at age three. “Just as soon as I could get my short little fat fingers around a pencil, I was drawing on everything,” he once said.

Rivera covered the walls and furniture with his work, prompting his father to give him a room of his own covered with blackboard. There the young Rivera spent hours creating worlds on his walls.

It’s probably no surprise then that the Mexican artist went on to not only become famous for his towering murals in adulthood, but emerged as one of the great Modernists of 20th-century art and arguably one of the most important painters in his nation’s history. Rivera’s artwork of the working class had a profound impact on the international art world, and among his many contributions, he is credited with the reintroduction of fresco painting into modern art and architecture.

After his work fell out of favor toward the end of the 20th century and his popularity was surpassed by that of his wife, Mexican surrealist painter Frida Kahlo, both Heritage Auctions and Christie’s say that Rivera is now continuing to gain the recognition he deserves and his prices are on the rise. Huge testaments to that include a private sale facilitated by Phillips auction house in 2016 of his painting, Dance in Tehuantepec, for $15.7 million, a record price for any Latin American work of art sold privately; and another painting, The Rivals, that set a new world auction record after selling at Christie’s for $9,762,500 in 2018. From the collection of David and Peggy Rockefeller, The Rivals not only set the auction record for a Rivera painting, but any Latin American artist. This beat the previous record held by a 1939 Kahlo painting that sold for $8 million at Christie’s in 2016. The painting, which he had produced for Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, one of his many American patrons, depicts a traditional festival in the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Rivera was born in Guanajuato in 1886. A child prodigy, he was enrolled full-time at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts, in Mexico City, at the age of 10. In 1907, he moved to Europe and spent most of the next 14 years in Paris, where he encountered the works of French masters including Cézanne, Gauguin, Renoir, and Matisse, as well as the Renaissance frescos of Italy. After Rivera returned to Mexico, he began painting for universities and public buildings. His large, public frescos brought art directly to the common man — circumventing the elite walls of galleries and museums. Throughout the 1920s, his fame grew with a number of large murals depicting scenes from Mexican history, technology, and progress.

“Gone was the doubt which had tormented me in Europe,” Rivera said later in life. “I now painted as naturally as I breathed, spoke, or perspired.”

In 1930, Rivera made the first of a series of trips to the United States that would alter the course of American painting. He began work on the first of two major American commissions for the American Stock Exchange Luncheon Club and the California School of Fine Arts. With these commissions, and all of the American murals to follow, Rivera explored and depicted the struggles of the working class. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, Rivera went to Detroit to paint a mural for the Detroit Institute of Arts commissioned by Henry Ford. In 1933, the Rockefellers commissioned Rivera to paint a mural for the lobby of the RCA building in Rockefeller Center. In depicting scenes of American life on public buildings, Rivera provided the inspiration for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration program. Of the hundreds of American artists who were employed through the WPA, many continued to address political concerns and struggles of the common laborer that had first been publicly presented by Rivera.

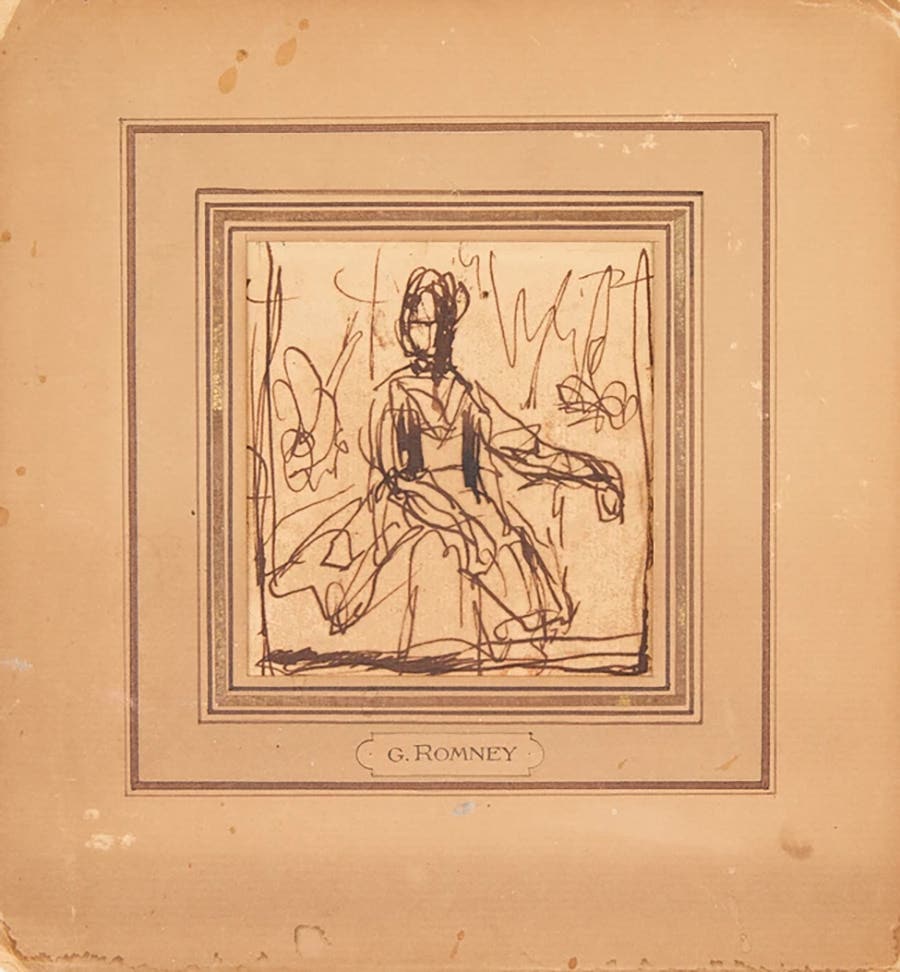

Although Rivera is best known for these murals, he also made a number of easel paintings, watercolors and drawings. One of the most common themes in Rivera’s work are children, both in scenes of everyday life and in portraits.

“It was normal for Rivera to paint these tender images of indigenous children that resonated with an American audience. Many who visited Mexico would bring back home pictures that captured a slice of Mexican culture,” said Virgilio Garza, head of Latin American Art at Christie’s. “Children represented the hope of a new generation in a new Mexico, the promise of a bright future, marked by equality and social justice. His boys and girls are always captured positively and with dignity.”

Rivera died in 1957 at age 70. For most of his life, he was hailed as a master, but over time, his reputation dimmed and his brand of social realism fell out of fashion to make way for movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop art. The artist also came to be seen as something of a propagandist for Communism during the Cold War years, and toward the end of the 20th century, his popularity was surpassed by that of Kahlo.

As for the 21st-Century, there are signs that Rivera’s reputation in the art world as a whole, and prices of his work, are on the rise again. “The record-breaking sale of The Rivals was the clearest example of that,” said Garza, “but not the only one.” Four of the top five prices for Rivera works at Christie’s have been achieved since 2015.

In recent years, Rivera’s work has appeared in a number of exhibitions alongside Kahlo’s, as well as one alongside Picasso's at Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2016-2017. In October, the Denver Art Museum opened the exhibit, “Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism,” that runs through January 24, 2021, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art will also stage Rivera exhibitions in 2021 and 2022.

According to Heritage, Rivera commands a wide range of prices and although his paintings can sell for millions of dollars, preparatory works are more affordable. Heritage sold Rivera’s Velorio for $40,000 in 2015. The work is highly desirable for its subject matter and medium. Typically, his original paintings achieve between $10,000 and $15,000.

Heritage said that as Rivera continues to gain the recognition he deserves, his market reflects that. His El Albañil was first valued at $800,000 to $1 million in 2012, but revalued at between $1.2 million and $2.2 million as of July 2018. Collectors and curators alike recognize Rivera’s role in the global modernist movement and his focus on the human form was decades ahead of its time. Rivera’s paintings are time capsules of the early 20th century, but feel contemporary as well. The government of Mexico officially recognizes his work as national patrimony. As Rivera’s paintings increase in stature, their value appreciates, said Heritage.

But there is a way in for collectors at lower price points. Both Heritage and Christie’s say Rivera’s works on rice paper are available at more accessible prices. Heritage sold his preparatory ink sketch on paper, Glassblower for just under $3,000 in 2004. At other auction houses, some other of Diego’s ink sketches have recently been selling in the $1,000-$2,000 range. These approachable prices make his work desirable for collectors.

“Understandably, people associate Rivera with his murals, but there’s a real market for his other work, too, that’s both strong and inclusive,” said Garza.