The Groundbreaking Leaps of Sculptor Augusta Savage

The artist and activist also blazed trails for other Black artists.

Artist Augusta Savage was born a Leap Year baby and once said, “It seems to me that I have been leaping ever since.” And she did, indeed, make groundbreaking leaps from the Jim Crow South to public attention in the Harlem Renaissance. Also an educator and activist, Savage was the first African American woman to open her own art gallery in America, forged a path for women of color in the art world, and catalyzed social change.

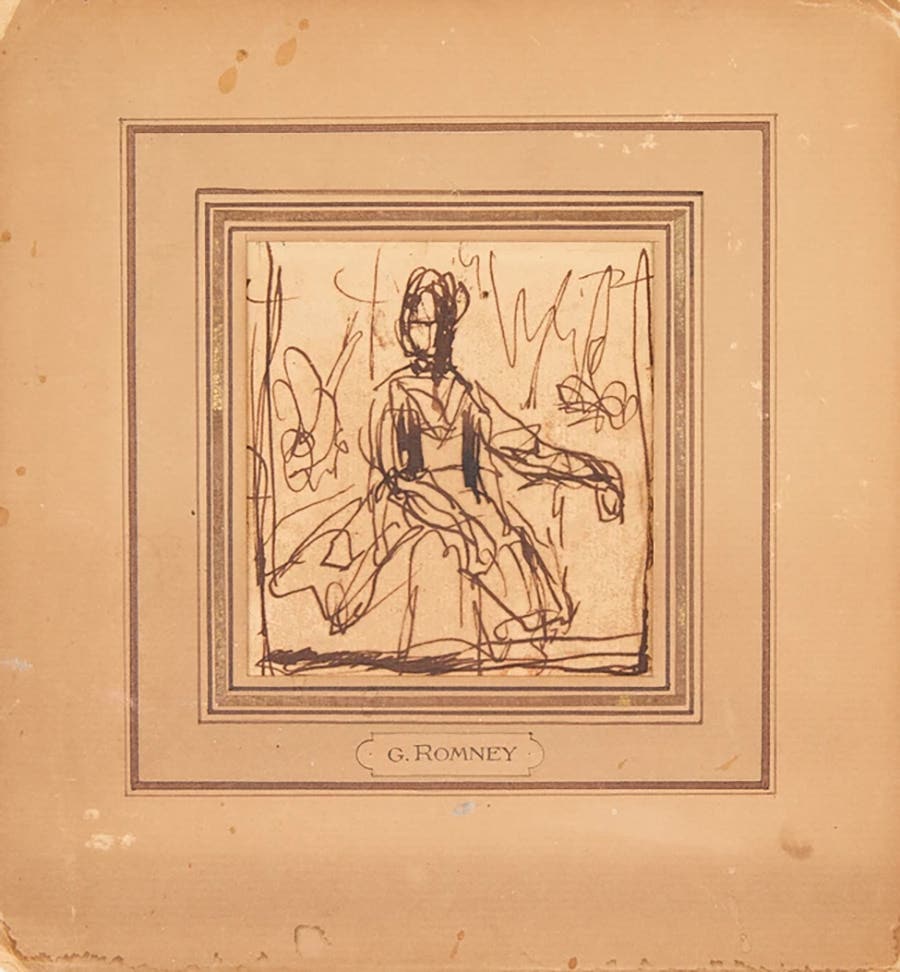

She also viewed the work of her students as being her legacy, but her own work is just as important, and some of her sculptures have been selling at auction for thousands of dollars. One, titled Gamin, circa 1929, achieved a personal auction record in December after it sold for $112,500 at Swann Auction Galleries.

Born on February 29, 1893, Augusta Christine Fells grew up in Green Cove Springs, Florida, the seventh of fourteen children of Cornelia and Edward Fells. As a brick-making town, it was full of natural red clay that Savage played with as a child and made things out of. But her father, a Methodist minister, strongly opposed his daughter’s early interest in art. He viewed her little clay figures as graven images and punished her for them.

“My father licked me four or five times a week,” Savage once recalled, “and almost whipped all the art out of me.”

A teacher recognized her talent, however, and encouraged her to continue creating.

Savage’s father moved his family from Green Cove Springs to West Palm Beach, Florida, in 1915. Continued lack of support from her family and the scarcity of local clay led to Savage not sculpting anything for almost four years, until a local potter gave her some clay, from which she modeled a group of figures that she entered in the West Palm Beach County Fair. The figures were awarded a special prize and a ribbon of honor.

Encouraged by her success, Savage moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where she hoped to support herself by sculpting portrait busts of prominent Blacks in the community, but that patronage did not materialize. Eventually, with less than $5 in her pocket, she moved to New York and settled in Harlem, where she cleaned houses to pay her rent, and studied at The Cooper Union School of Art. It was the height of the Harlem Renaissance, and she found herself in the company of the prominent writers and activists of the 1920s, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. Savage joined them while simultaneously combating poverty and racism.

In 1923, she applied to a summer art program in France. Though she was accepted into the program and received a corresponding scholarship, the French government declined admitting her after learning she was black. They felt that traveling with white women would be uncomfortable for her.

“As soon as one of us gets his head above the crowd, there are millions of feet ready to crush it back again …” Savage wrote in a public response, which was printed in the New York World. “For how am I to compete with other American artists, if I am not to be given the same opportunity?”

It took six years of activism, but Savage was eventually permitted to study in France. That struggle permanently fused her ideals with her art, which explores the African American experience in the Jim Crow era.

“She set her focus on race-based art and activism that would last for the rest of her life,” said Wendy Ikemoto, the associate curator of American art at the New-York Historical Society.

Ikemoto coordinated an exhibition of Savages’s work at the historical society in 2019. She said it was the first exhibition to look at her career, and also how she struggled through poverty and racism.

“She often didn’t have the funds to cast her sculpture in bronze, or the money to store them. Many were cast in plaster and painted with shoe polish to make it look like bronze,” Ikemoto said.

During the Great Depression, Savage found work by running an art school and creating portrait busts of her fellow African American activists, but Roberta Smith, writing for The New York Times, identifies the artist’s portraits of everyday people as her strongest works: “Savage’s radicalness lies in her determination — one shared with many Black artists today — to populate art with active representatives of Black life.”

Gamin, her most famous portrait, was created with that goal in mind.Modeled after her nephew, Ellis Ford, the bust was intended to represent the countless young boys who populated the streets of her city.

“What’s so remarkable about this work is that, quite simply, it presented an African American child in a realistic and humane fashion,” said Ikemoto. Thousands of kids came to see Gamin on exhibit, and “they saw themselves as fine art.”

In addition to the December sale of Gamin at Swann, a few others also sold in 2020: one for $35,000 at Black Art Auction, one for $28,800 at Case Antiques and one for $15,000 at Heritage Auctions. Another Gamin sold in 2019 at Swann for $68,750.

Following her return to New York in 1932, Savage established the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts and became an influential teacher in Harlem, and two years later, she became the first African American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. She was also appointed the first director of the Harlem Artists Guild during the 1930s. Using her appointment in 1936 as an assistant supervisor in the Federal Arts Project (a division of the Works Progress Administration or WPA), she fought for commissions for black artists and to have African American history included on public murals.

When the 1939 New York World’s Fair commissioned Savage to make a sculpture symbolizing the musical contributions of African Americans, she produced a monumental work called Lift Every Voice and Sing, inspired by the lyrics of James Weldon Johnson’s poem of the same name. World’s Fair officials changed the name to The Harp.

Savage spent two years creating the sixteen-foot high sculpture, made of painted plaster,

“The strings of the harp are formed by the folds of choir robes worn by 12 African American singers,” Ikemoto explained. “Then, the soundboard of the harp is formed by the hand of God.” The singers then become instruments of God.

Five million visitors saw The Harp and it became one of the fair’s most photographed objects. Ikemoto said it was destroyed — smashed by clean-up bulldozers — at the end of the fair, along with all of the other art.

When surviving miniatures of The Harp reach the market, they draw attention. Two sold in 2020 at Black Art Auctions: one for $13,750 and the other for $11,250. A number have also sold at Swann over the years including one for $21,250 in 2019, one for $15,000 in 2017 and another for $23,750 in 2014.

Also in 1939, Savage opened the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art in Harlem, which was America’s first gallery for the exhibition and sale of works by African American artists. Her studio was the foundation for some of the most well-known figures of the Harlem Renaissance, and Savage taught artists including abstract painter Norman Lewis, figurative painter Jacob Lawrence and portrait artist Gwendolyn Knight.

Ikemoto said that Savage recognized the temporary nature of her work, and preferred to view her legacy as the skills she taught her students and followers in Harlem, many of whom would later establish successful careers.

“She’s been lost to history, compared to her well-known students, who had increased attention,” said Ikemoto. “… She’s a great reminder of the crucial role of having a multiplicity of voices in the public space.”