Antique Technology: Fiction inspires pre-cinema gothic illusions

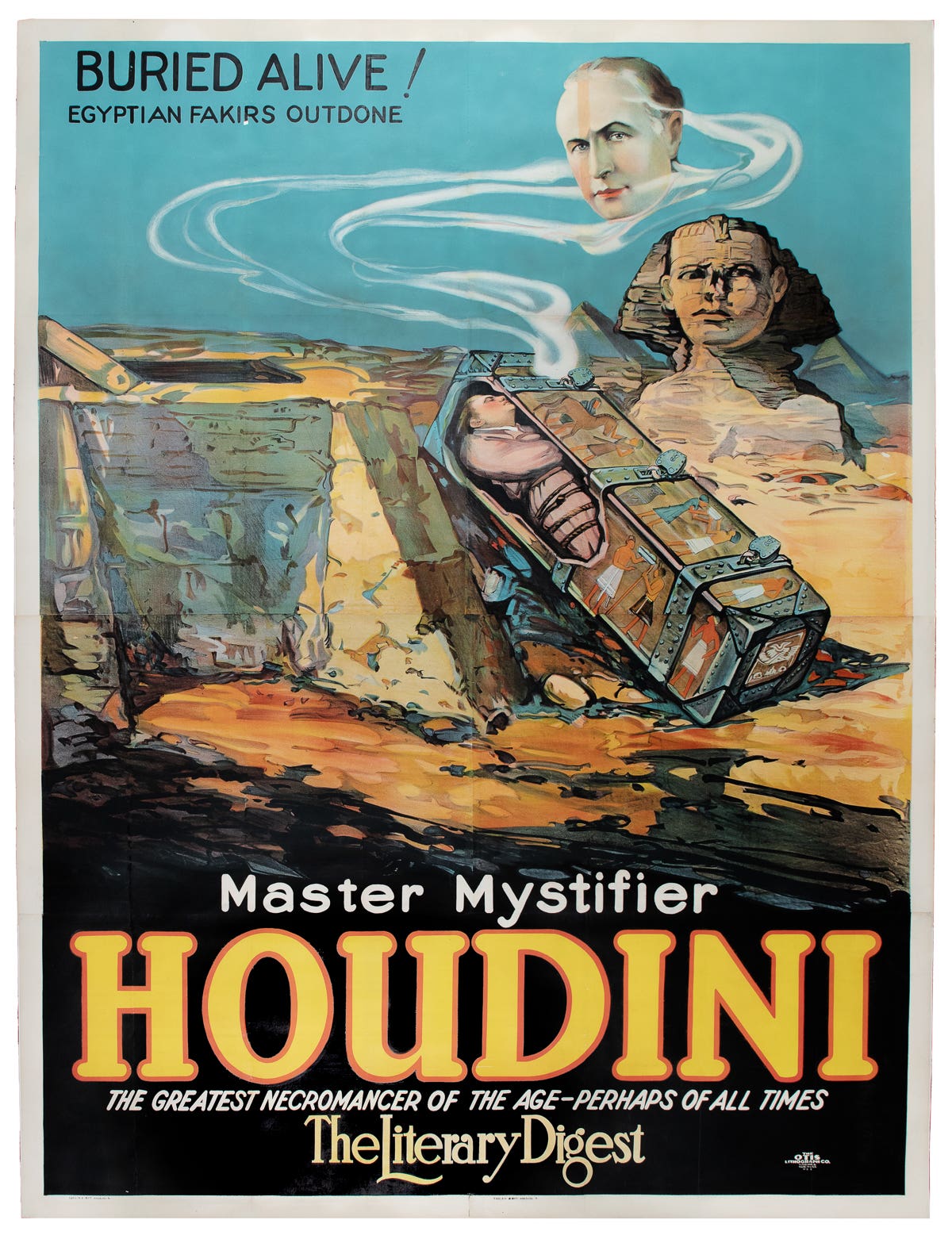

Now antique, pre-cinema technology brought what was previously experienced only in the imagination before the eyes of an enthralled audience.

The path to creating pre-cinema gothic illusions is traceable through popular culture. The quest for frights and chills lead to the development of pre-cinema technology. This now-antique technology brought what was previously experienced only in one's imagination before the eyes of an enthralled audience. On September 29, Auction Team Breker will be holding an auction of Photographica & Film Auction, which features many selections of pre-cinema antique technology and props used in the creation of gothic illusions.

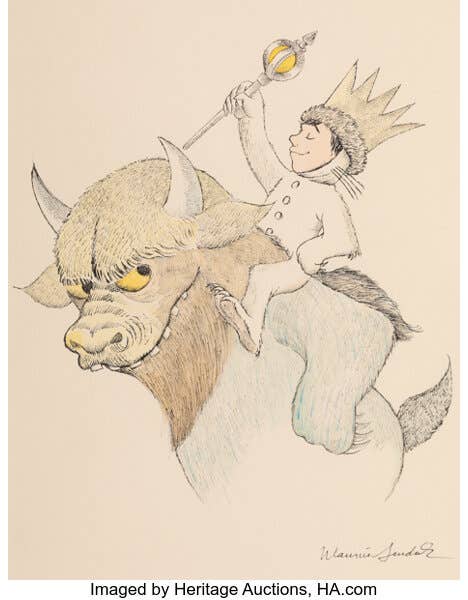

The recipe for Gothic fiction is a simple one, according to an anonymous author in a 1797 edition of the Spirit of the Public Journals. The rise of the Gothic Novel began with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto in 1764, followed by tales of suspense and the supernatural such as Anne Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and Matthew Lewis’ The Monk (1796).

Gothic’s preoccupation with ghosts, the demonic and states of extreme fear opened the cellar door to specters that haunt popular culture to this day. Thanks to Gothic literature we have the modern horror film, the final girl of the 1970s slasher sub-genre and unforgettable anti-heroes such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Improvements in antique technology

Improvements in lenses during the late 18th century played their part in the birth of Gothic fiction by projecting apparitions and illusions into the public imagination. The mastery of optics was often associated with the diabolic and the devil, whose medium is illusion rather than creation. The first recorded use of the term “l’art trompeur” (the deceptive art) to describe optical effects occurs in a description of a magic lantern show in Nuremberg by French traveler Charles Patin in 1674.

One hundred years later the Phantasmagoria lantern show appeared in Germany. The Fantascope, perfected and patented by the Belgian showman Etienne-Gaspard Robert in 1799, was a complex creation that produced the earliest projected special effects. Its ‘cat’s eye’ lens and mechanical autofocus conjured up ghastly apparitions that appeared to float or rush upon the terrified audience, much like Lumière short film “L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciota” is said to have done to its audience in 1896.

The Fantascope could also be used to project opaque objects as 3D illusions on a virtual screen. The “Moisse Molteni Skeleton” is of 3D illusions (a classical bust, a winged death’s head and a grim reaper) illustrated in the Alfred Molteni’s Instructions Pratiques sur l’Emploi des Appareils de Projection.

The skeleton’s discovery in the attic of the Château de Moisse in 1991 could have come from the pages of Anne Radcliffe herself. The illusion depicts a painted sarcophagus whose lid lifts as the skeleton marionette in a monk’s cowl, jaw chattering and eye sockets hollow, clambers out. Not only is the mechanical illusion a visual artefact and a cultural reference object of its time, but an important link between projected still images and the dawn of cinema.

Optical progress

Mystery, spirits and supernatural terrors experienced in a landscape characterized as majestic, melancholy and grand were key ingredients of Gothic fiction. Even before the invention of Daguerreotype photography in 1839, optical progress had led to a new interest in perspective. The Myriorama (or “Many Thousand Views”) was a collection of cards that combined into a multitude of different landscapes. In continental Europe, peep boxes for studying paper perspective views, known as vue d’optiques, (through a lens) were a fashionable entertainment. Neo-classical architecture, famous landmarks and sublime scenery were favorite subjects in the mysterious wooden boxes with inset lamps and lenses.

On a smaller scale, the popular Polyorama Panoptique, produced in Paris during the second quarter of the 19th century, featured a flap in the lid that enabled the viewer to transform the hand-colored paper scene from day to night by varying the amount of light falling onto the image. The changes in the metamorphic box could be spectacular as well as surprising: windows are illuminated, fireworks light up the sky and crowds gather and disperse.

For more information about the September 29 Photographica & Film auction from Auction Team Breker, offering examples from all these visual entertainment relics, visit

www.breker.com.

“Take – An old castle, half of it ruinous

A long gallery, with a great many doors, some secret ones.

Three murdered bodies, quite fresh,

As many skeletons, in chests and presses …

Mix them together, in the form of three volumes,

To be taken at any of the watering places before going to bed.”

~ “Terrorist Novel Writing”