Hateful Things

David Pilgrim and the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia use objects of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote social justice

A noose hanging from a tree.

A sign that reads: “No Negroes Allowed After Sundown.”

Photos of Ku Klux Klan members posing next to a beaten and bloody African American.

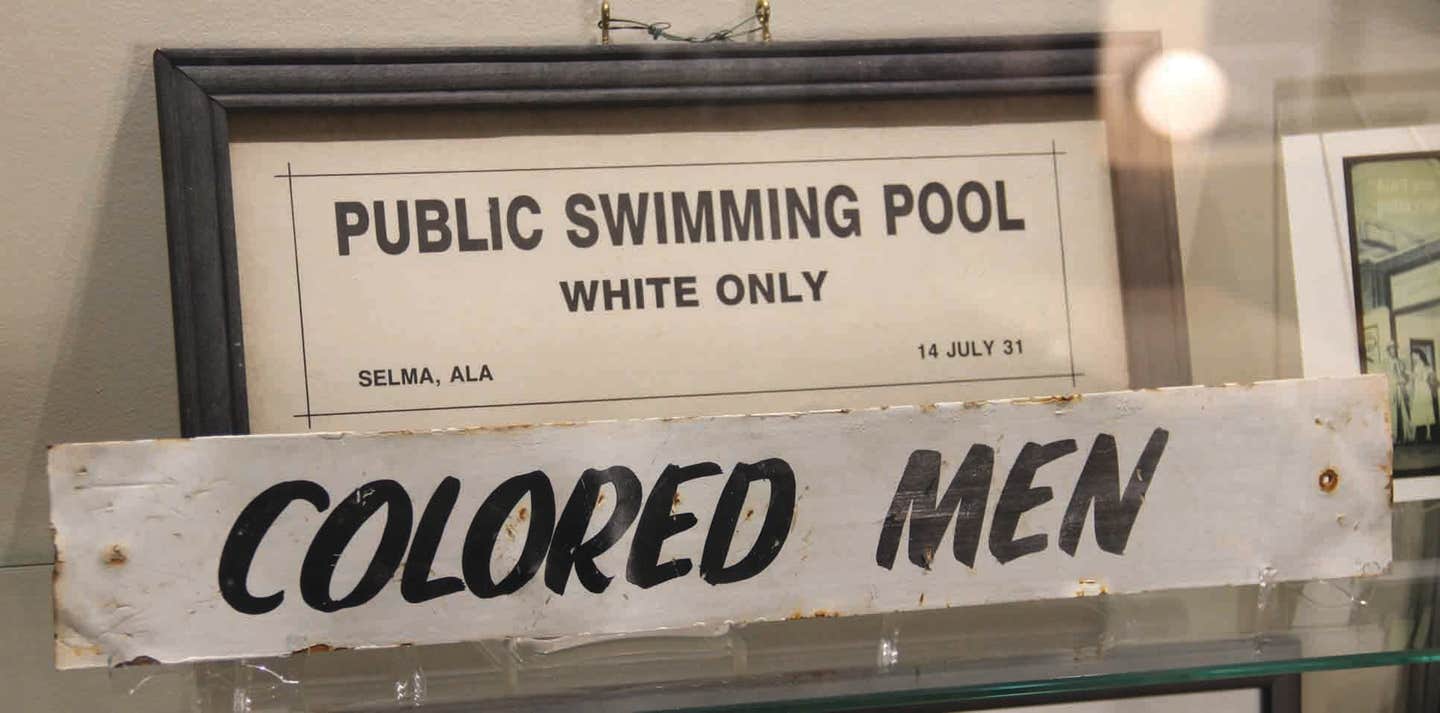

These are just a few of the powerful, incomprehensible images that show how Black men, women and children have suffered intolerance and social injustice over the past couple hundred years in the U.S. They are also signature pieces on display at the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia on the campus of Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan.

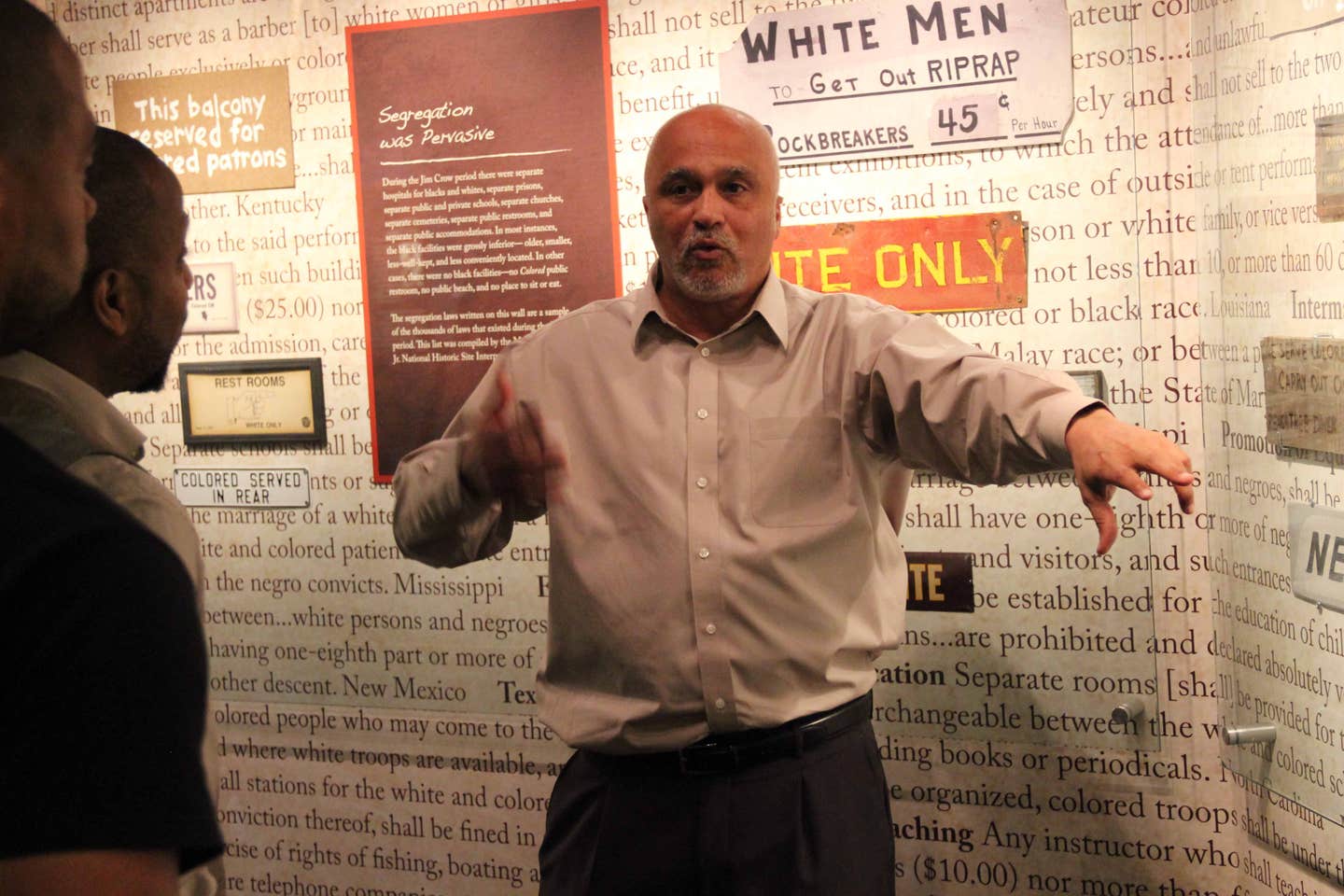

“I think we’ve done a great job in terms of facilitating good discussions about race, race relations, racism and about inclusion,” said Dr. David Pilgrim, museum founder and curator. “In this country, I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, we like heavy history. It’s history that paints us as smart, brave and exceptional, and we cherry pick and ignore instances where people who were disfavored were mistreated. The museum documents what happens in this country’s past and uses that to encourage people to confront that past.”

The anti-racism facility, which is the only one of its kind in the nation, has about 8,000 objects on display that depict everything from the Jim Crow era to Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement to pop culture items found today.

“Despite the name on the door, we don’t really say to a person, ‘This object is racist,’” said Pilgrim, who is also the vice president of diversity and inclusion at Ferris State. “Of course, I have my own personal opinions, but really what we do is we introduce objects and we ask people, ‘What is it you see?’ Then we can answer questions about the origins of the objects, if it’s a caricature and what could that mean, what might have been the impact of that object. But really, we’re trying to get people to do some thinking.”

Since Day 1, it’s been Pilgrim’s exceptional vision that has made the museum a success. In 1996, Pilgrim donated his collection of racist memorabilia – about 3,500 pieces – to the college. The items were confined to a space before a much-needed museum was put together in 2012. It has thrived ever since.

Pilgrim started collecting racist memorabilia in the 1970s. He would stop at every antique store, flea market, garage sale and pick up items. His motivation for collecting offensive pieces is not so easily explained.

“I wish I had an answer for that,” Pilgrim said. “I think going to a historically black college where teachers sometimes use objects to teach, I think made a big impression on me. Then wanting to teach about race and finding early on that there’s a power in an object – that object helps me document what I say, also, for the people that think you’re just making it up. It was just a long journey.

“I was just obsessed with the objects and what they meant and trying to understand the minds that created them and then trying to use the objects to teach with.”

Museum educator and collections database administrator Cyndi Tiedt has witnessed the impact of the museum through the thousands of visitors who check out the exhibits each year.

“I think it’s a fantastic educational piece,” Tiedt said. “The longer I work there, the more I see the real deficit in parts of the educational system, particularly in Michigan, teaching from a young age about the true history of our country.”

Tiedt, who has worked at the museum for three years, is originally from Australia. Now an American citizen, she didn’t have a great deal of knowledge about U.S. history when she accepted the job at the museum.

“As I started to learn more, I started to recognize a lot of these objects and a lot of these messages hit home, particularly objects that were misrepresenting our own indigenous population,” Tiedt said. “As a white person in the museum, I think any person coming into the museum, you can’t help but be affected by these objects. Some of them are more explicit than others and are incredibly hurtful, even to me as a white person to see objects that were so grossly negative toward our fellow Black Americans.”

Even before entering the museum, visitors are struck by how much information is outside the building.

There is a timeline where people generally spend time browsing. In addition, there are artifacts and a collection of more than 200 objects that denigrate Native Americans.

“I think that surprises people, because they didn’t expect to see that at a Jim Crow museum,” Pilgrim said. “That’s our way of saying that we believe Martin Luther King when he said, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’”

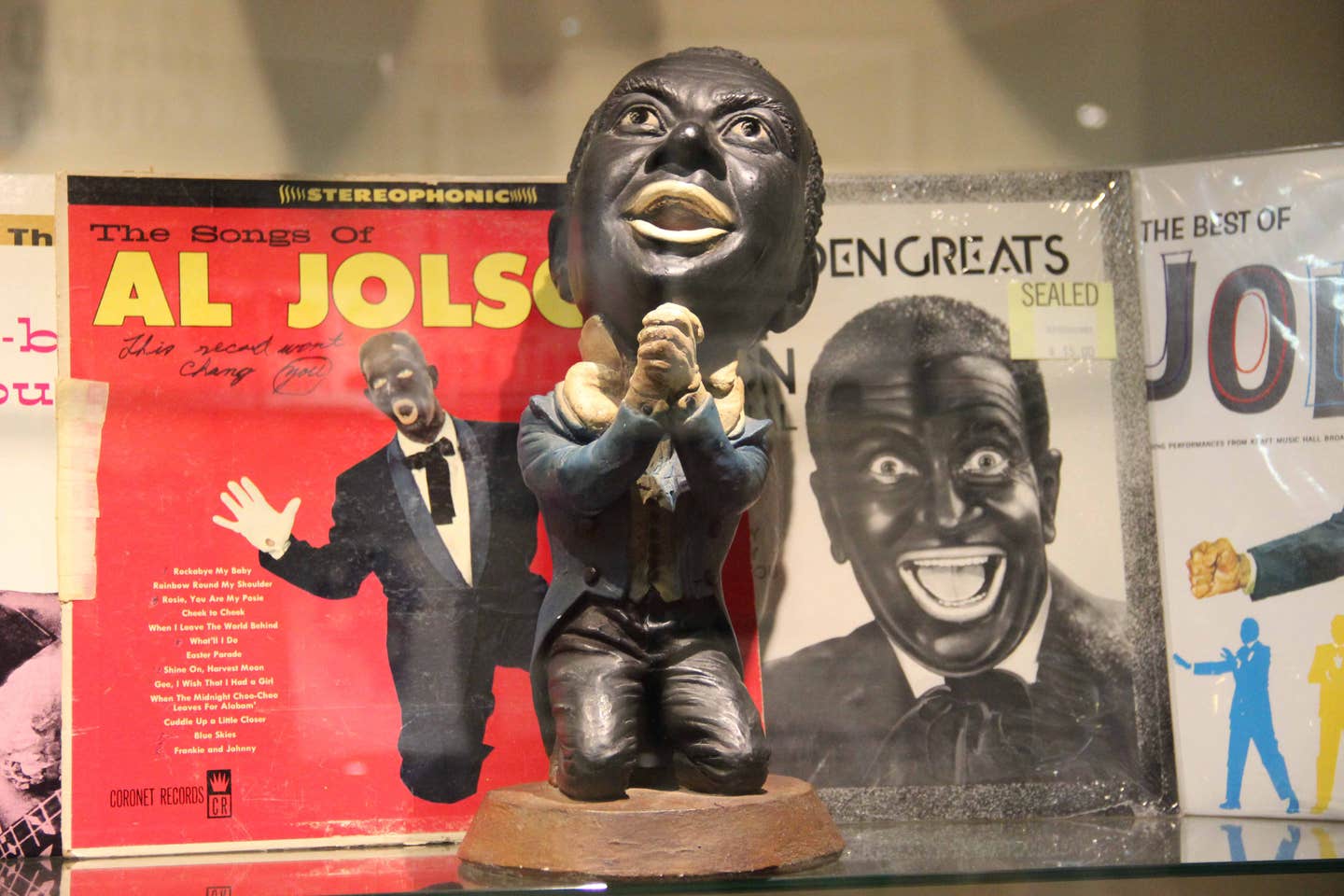

Once inside, the journey really starts. There are six exhibits: Who and What is Jim Crow, Jim Crow Violence, Jim Crow and Anti-Black Imagery, Battling Jim Crow Imagery, Attacking Jim Crow Segregation and Beyond Jim Crow.

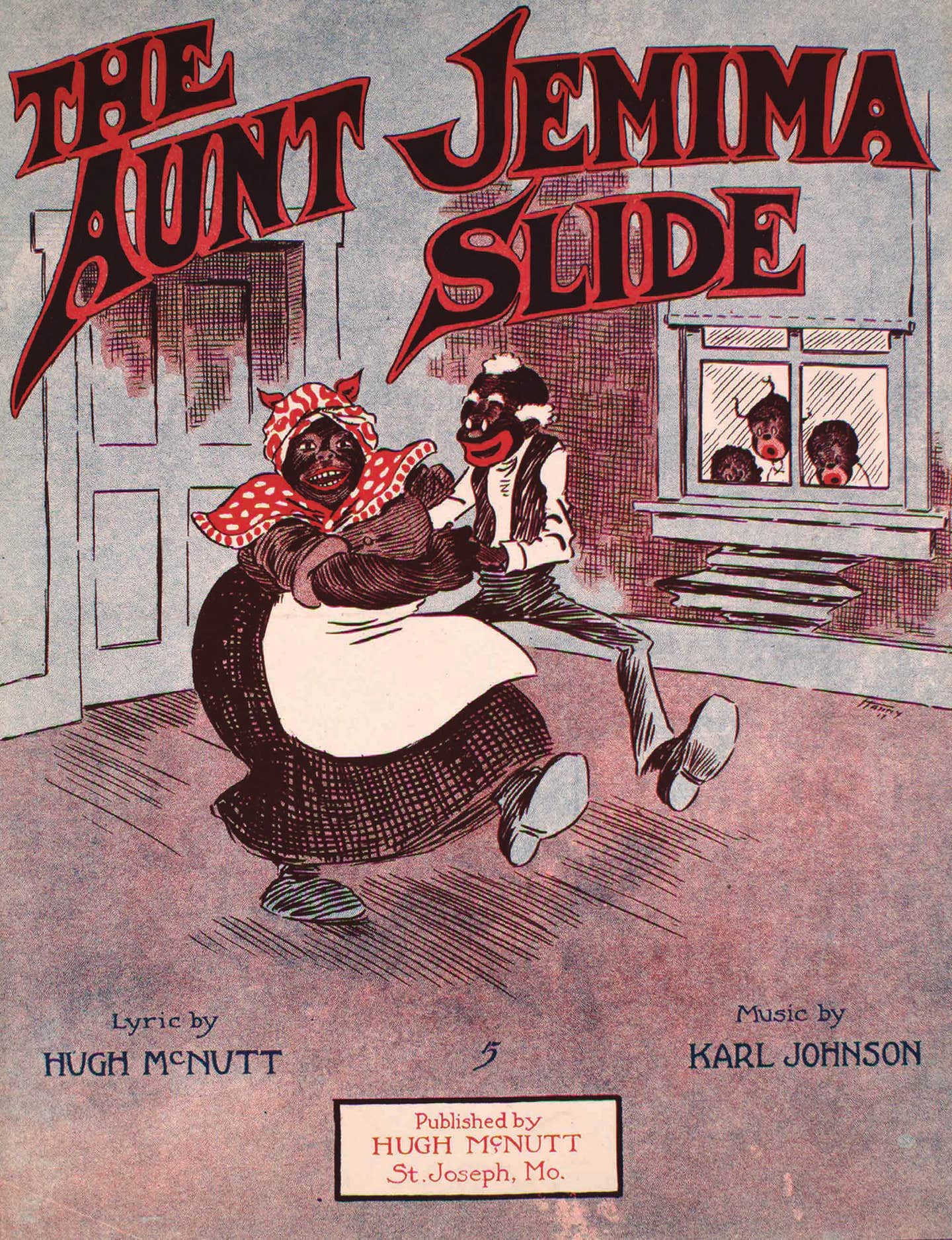

“The most difficult would be the section which details Jim Crow Violence, because it is what it is,” Pilgrim said. “We have a lynching tree. We show videos of violence. We show the connection between violence and the system, because the system could not have worked without violence. That’s probably the most difficult one. The majority of the museum would be sections dealing with everyday objects: the postcards, the children’s books, the toys, the sheet music. Then we talk about how African Americans push back with art, with the civil rights movements, with achievements and the like. Then we have a small section on the civil rights era.”

One of the most impactful sections is on modern expressions of Jim Crow, Pilgrim notes. It depicts objects created in the last ten years that have the same sorts of stereotypes and caricatures of African Americans. There is one telling section that presents objects that racially defame President Barack Obama. He’s despicably portrayed as a monkey, a savage, a cannibal and a Tom.

There are many objects in the museum that speak volumes to Pilgrim, but one really stands out in his mind as the most important piece.

“We have an ink pen that I first believed was the ink pen that Lyndon Baines Johnson used to sign the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law,” Pilgrim said. “But we’ve done more research and we now believe it’s one of the pens he used to sign the 1968 Voting Rights Act, which is just as significant. And so, for me, that’s the kind of piece that most appeals to me.”

It may seem counterintuitive, but the heinous and challenging items on display don’t create the best conversations, Pilgrim said. It’s the pieces in the museum reminding people of an object they had in their homes that prove to be the most thought provoking.

“When we have the kitchen with the so-called mammy objects, I think that those objects over there, the cookie jars or even something like a book like ‘Little Black Sambo,’” Pilgrim said. “Those kind of pieces resonate with people because they are familiar with them, and they’re being asked to see those pieces in different ways.”

The oldest item, which is one of the most recent finds by Pilgrim, is a lawn jockey from the 1830s. “The Faithful Groomsman” is a cast iron hitching post with the figure of an African American man on a burlap tied bale. It was an expensive piece, but Pilgrim knew he had to pick it up when he had the opportunity.

“I needed it because it helped us tell the story we were telling,” Pilgrim said.

Once people finish up walking through the museum, a common question that arises is: “What do we do now?” How does Pilgrim respond?

“Historically, we have not given them an answer,” Pilgrim said. “We have facilitated questions where we all answer. In other words, I think it’s too simple just to say, ‘OK, now do this.’ We have a little space, which is a dialoguing room and that space is to get people to come to whatever that answer is. I think it’s too easy to and almost simplistic and naïve to tell people what they need to do. I think a better approach is groups of eight, ten, twelve people to sort of muddle through them.”

During a typical year, the museum draws between 5,000 and 6,000 physical visitors. About 30% of the guests are college students on a class tour. People come from all over the country to check out the museum. Each year students from Kent State University (Ohio) make a trip to the museum in west central Michigan.

According to Pilgrim, it tends to be racially diversified groups – from all occupations, races and ages – that frequent the museum.

As the museum educator, Tiedt heads group tours and educational experiences for high school, community groups, church groups, police groups and many others.

“I think the museum’s incredibly important to fill the gap,” Tiedt said. “There are students in my experience and many adults who are also lacking this basic information. By preserving these objects and documenting these narratives, I think it’s an incredibly important mission for everyone to learn from the museum and to learn the true history.”

The museum has had to take a little different approach this year and relied on virtual visits. Due to COVID-19, the museum shut down in March and still hasn’t reopened to the public. Virtual tours are available online. The museum’s YouTube channel had approximately 750,000 views in 2019.

Pilgrim said the museum has become a destination sight for travelers, and the success is rubbing off in people wanting to donate items. The museum continually receives donations, about 1,500 objects per year. That includes a million-dollar collection of photographs that recently came in.

Pilgrim figures the museum has about 8,000 pieces in storage, although some are duplicates.

“It doesn’t hurt what we do when we have 50 of the same thing, because it actually helps us make the point about how common certain objects were,” Pilgrim said. “I don’t often send boxes back, but we have filled up now a couple of storage rooms.”

Along with tangible donations, the museum has received an abundance of monetary donations. The valuable combination of those two types of gifts will allow the museum to build a new facility using 100% donor dollars. Pilgrim said a standalone building is being planned on Ferris State’s campus, but there aren’t any start or end dates set.

The museum’s 3,800 square feet offers enough space for six exhibits and Pilgrim is planning to expand by adding two more exhibits. A new museum would be about five times larger than current building

In light of current civil unrest, as the nation deals with police shootings and subsequent protests, Pilgrim realizes just how important the museum’s role is in telling the story of the African American experience.

“I believe this new social justice movement set off by the killing of George Floyd has caused all of us, corporations, police departments, universities, individuals, to look at the role that race plays in our society,” Pilgrim said. “It is always the right time to be having difficult discussions about race and social justice.

“The museum itself has gotten more attention because of national events,” Pilgrim said. “But if we’re doing our work right, we’re always having these discussions.”

Greg Bates is a versatile freelance writer from Green Bay, Wisconsin, who has written on everything from vintage chainsaws to pop culture collectibles to The Henry Ford Museum.